From the Unsettled Dusts of Manipur

Image courtesy: Speaking Tiger

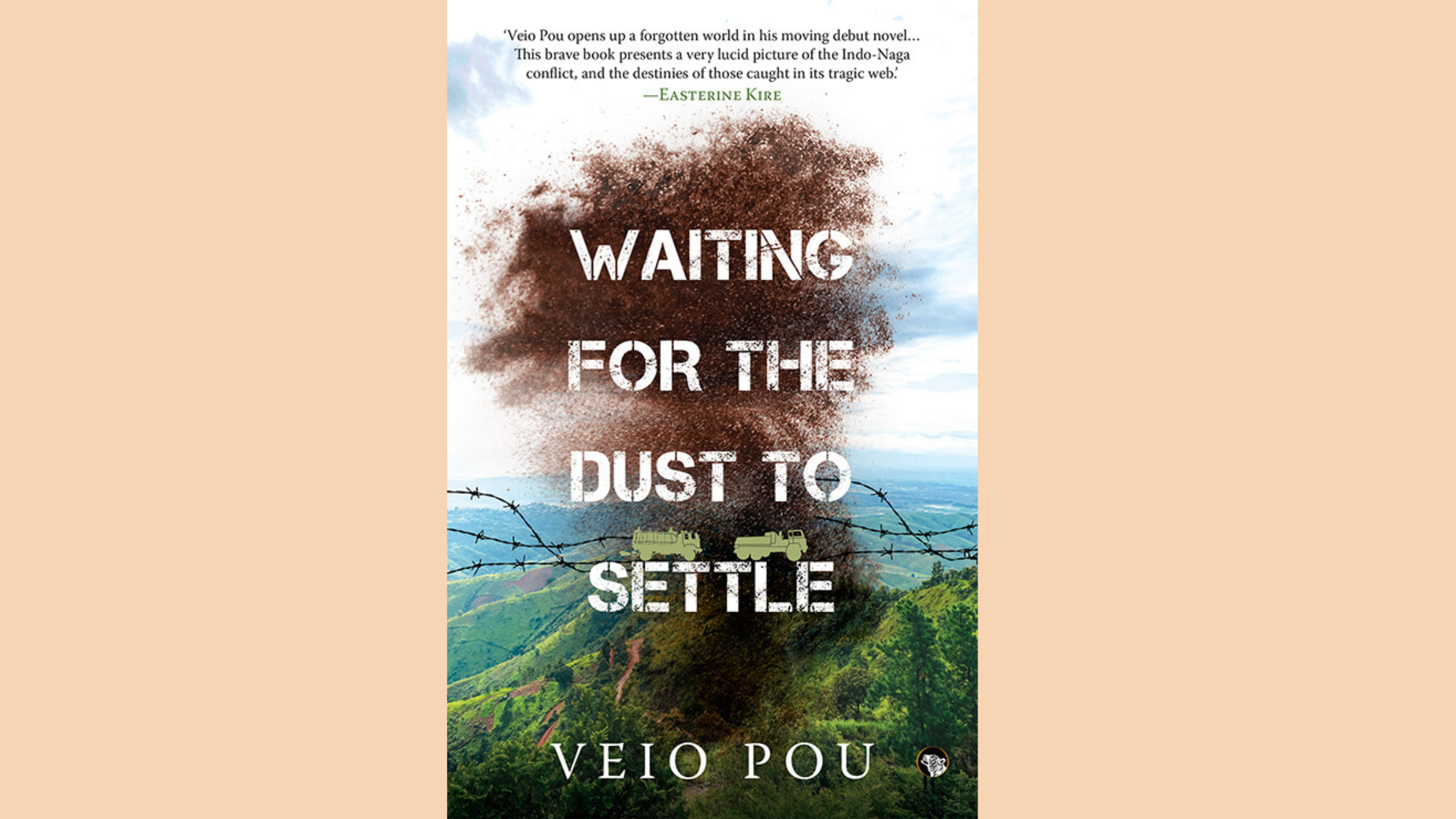

“These are more than just stories. They are our history.” Veio Pou’s debut novel Waiting for the Dust to Settle (2020) narrates a story drawn from real-life incidents from Operation Bluebird in Manipur, blending the personal and the political.

In July 1987, the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) attacked one of the Assam Rifles’ settlements, killing nine soldiers and fleeing away with the outpost’s arms and ammunition. What followed in response was ‘Operation Bluebird’: a military crackdown on innocent villagers, series of arbitrary arrests, and humiliation of people in Oinam, a village in the Senapati district.

“Even after 28 years the memory of those atrocities is alive,” Nandita Haksar wrote for Scroll when all charges against the Assam Rifles, for gross violation of human rights, were disposed of. It’s those atrocities and unforgiving memories that form the core of Veio Pou’s debut novel Waiting for the Dust to Settle (2020, Speaking Tiger). Set in Manipur in the 80s, the story draws from real-life incidents, blending the personal and the political.

An unfulfilled dream

Ten-year-old Rakovei is fascinated with army men. He wants to be like them. Being in the army will earn him respect, he believes, make him fearless, and give him power. He sees their convoys passing by on NH 39 from the front room of his house. The sound that the vehicles make is “music” to his ears.

Grandmother Toukhue believes stories are remembered when sung. “When we grew up, it was a matter of pride to be able to sing songs and narrate tales.” She’s afraid that the modern education system is making children strangers to their history.

On Christmas, Rakovei requests for a kids’ army uniform as a present. His parents—Khole and Sanei—insist for a different gift, but eventually, acquiesce to their only child’s insistence. The family visits their native village, Phyamaichi, for Christmas, a village formed in 1944 where everyone is related to one another. Rakovei is attracted to village life, loves spending time with his cousins, and listening to stories from his grandmother, Toukhue. She “was a treasure trove of stories—stories about animals, spirits, people, and all sorts of things about the grand and glorious past.”

During the festivities, Rakovei’s uncle, Lounü, asks him what he wants to become when he grows up. He pauses at first, fearing expressing his desire in front of people who despise the army, and then, speaks his mind. Sanei, the boy’s mother, is disturbed by this. She tells Rakovei of the story of how her father—Rakovei’s grandfather—was interrogated by the army because he was an informant for the undergrounds (UGs). He was given electric shocks and had to bear all sorts of torture until the day he was discarded lifeless at their doorstep. She still remembers the horror of imagining her father in this state. A desire for vengeance grew in her heart.

But it wasn’t his mother’s plea that made him detest army men, it’s his uncle, Lounü’s. Fed up of growing corruption in the government office where he was applying for a job, Lounü threw a chair at an official. The story was covered by local newspapers, and he had to change his name to Lenny to protect his identity. But he was soon on the army’s radar. ‘Lenny’ was also interrogated during the infamous Operation Bluebird, and thrashed and abused to the point that his back ruptured during the investigation. “Looking at his uncle, now immobilized because of them, a fresh anger sprouted inside [Rakovei]. Somehow, something changed in him that day.”

‘Do they tell you stories like I tell you?’

The Northeast has a rich tradition of oral storytelling. There’s even a story to explain the wrath that the Brahmaputra river unleashes: A beautiful girl married a snake, who transformed himself into a handsome man. When she became pregnant everyone knew it’ll be an unusual birth. She was made to give birth into a pot of boiling water. Of all the snakes that were born, all died except one whose head was smeared. “Since that time, people believed that the ‘smear-headed snake’ appeared whenever the river swelled to claim lives as revenge.”

Rakovei’s grandmother is a great storyteller. She believes stories are remembered when sung. “People of this generation,” grandmother Toukhue believes, “don’t care about knowing or learning stories that have made us what we are!” For her, these “are more than just stories. They are our history. When we grew up, it was a matter of pride to be able to sing songs and narrate tales.” She’s afraid that the modern education system is making children strangers to their history.

Rakovei, however, becomes well-versed to his land’s history. So does the author Veio Pou, as he cleverly presents insights in this book that are missing in most news articles and reports from the Northeast.

The levers of fiction and a longform reportage, however are different. Fiction doesn’t necessarily need to respond to the news and facts of the world, but even when the current events of this outside world drive the narrative, they don’t need to form the core of the work. “Form follows function,” write Bryan A. Garner. Real life can appear as subliminal text and provide organic movement to the story. The structure of Pou’s book however, seems overwhelmed with Pou’s own knowledge of history and current events, which weigh down even the fiction to read more like reported news.

There are several instances in the novel where the narrative stops and the reporting begins. History is taught, for example: “The Assam Rifles military post at Oinam Hill village was set up in the mid-1960s. It was also around this time that the first ceasefire between the Government of India and the Naga National Council (NNC) was brokered by the Peace Mission consisting of Bimal Prasad Chalika, Rev. Michael Scot, and Jaya Prakash Narayan.” And social conditions are explained: “The polarization of these groups had been sharpened by the emergence of insurgent groups that vowed to fight for the rights of each group. Therefore, the state continued to remain a ‘disturbed area’ for various reasons.”

Veio Pou. Image courtesy: Speaking Tiger

These are besides the attempt to showcase the character Joyson’s intellectual interests in the Indo-Naga conflict. Besides the literary move to sieve his speech in a gathering to help readers empathise with victims of the Oinam incident, Joyson’s verbose explanations—such as the definition of the insulting term ‘chinky’—are odd and clunky.

I wondered if there was a real need by the author to list down books on the Indo-Naga conflict. I am also conflicted on the novel’s rushed and unsatisfactory ending. As a result of an uncaring attitude toward the narrative, the novel slips into overindulgence and tangential digressions, which could’ve been weaved into the story more organically.

There is a wide variety of books which have explored life amidst the tensions in the Northeast. I’m reminded of Jahnavi Barua’s Undertow or books by authors such as Easterine Kire and Temsüla Ao. There are also many examples of novels that have managed a smooth balance between the news and the narrative, such as The Empty Room by Sadia Abbas. Abbas articulates the story of unrest and revolution in 70s Karachi, and does so without stunting the narrative with details about contemporary developments. Instead, she creates an enriching personal and political conflict zone, making this fictional account unputdownable.

Everyday Survival

Despites its drawbacks, however, Waiting is well-worth a read, with unforgettable scenes that leave a gut-wrenching impact on the reader. Pou details the everyday survival of citizens in Manipur during the conflict of the world outside, the racism faced by students from the Northeast in the capital, and the gory account of a woman who was forced by the army to give birth in front of the whole village. The child—a boy—dies a few hours after the birth.

The army continues to “dismiss sporadic incidents of violence here and there as ‘law and order’ problems.” When it comes to the Northeast, Pou writes, “There is a lot to blame on the government’s neglect of the region for too long.” The UG army has created a menace, too, extorting money from the native people in the name of taxation. “Once the people had feared the Indian army, but now they were afraid of the bullets of the undergrounds,” Pou adds. The author’s note in the novel has semblance in Temsüla Ao’s lament, too: “Nagaland’s story of the struggle for self-determination started with high idealism and romantic notions of fervent nationalism, but it somehow got rewritten into one of disappointment and disillusionment because it became the very thing it sought to overcome.”

To underline this issue, to restart negotiations for a better world, and to renew appeal for peace and harmony during contemporary times—when there’s little to no hope from the media to unearth such stories—one needs books like Waiting for the Dust to Settle. There are many more stories waiting to be told, and to be told better.

Title: Waiting for the Dust to Settle; Author: Veio Pou.

Publisher: Speaking Tiger; Pages: 224; Price: ₹399.

***

Saurabh Sharma is a reader and a writer. He works as a writer in an IT research and advisory firm in Gurgaon. He reviews books and pretends to write on weekends. You can find him on Instagram: @writerly_life and Twitter: @writerly_life.