Ink(ed) on Flat Surfaces: A Show on Studio Practice

A view of the basement floor of Gallery Espace, staging another half of the show “Ink”, including works by Gautam Bhatia, Partha Pratim Deb, Amitava Das, Madhvi Parekh, and Dilip Ranade. Image courtesy: Gallery Espace.

Featuring artwork by some of India’s greatest artists, “Ink” at New Delhi’s Gallery Espace plays the role of a catalyst in thinking beyond the normative practices of art-making, art showcasing, and curatorial interventions.

At “Ink”, a group art exhibition at New Delhi’s Gallery Espace, Gargi Gupta’s curatorial intervention looked at the artists’ practices of setting a primary ground, before they venture to perform their art. In my opinion, the very practice of art indulges a performance and, unknowingly, Gupta has been able to work with the richness of this argument. Also, to my eyes, a single line can perform the role of a final task in art-making. Given these two very opposing views, one is invited to look at a collection consisting of artworks that stage the initial grounds of art-making as well as its impact of finality.

Interestingly, both these arguments also hold the debate on the act of movement, synthesizing the many facets of performance, where these performances go unnoticed or undefined. The marked strategy of staging an artwork in its complete form—because of the various traditions of productivity—has fundamentally been implemented in first-world countries, many years prior to the South-Asian gallery structure. In the process, art (objectively) has become a complete product by itself, without the importance being placed on the presence of the artist.

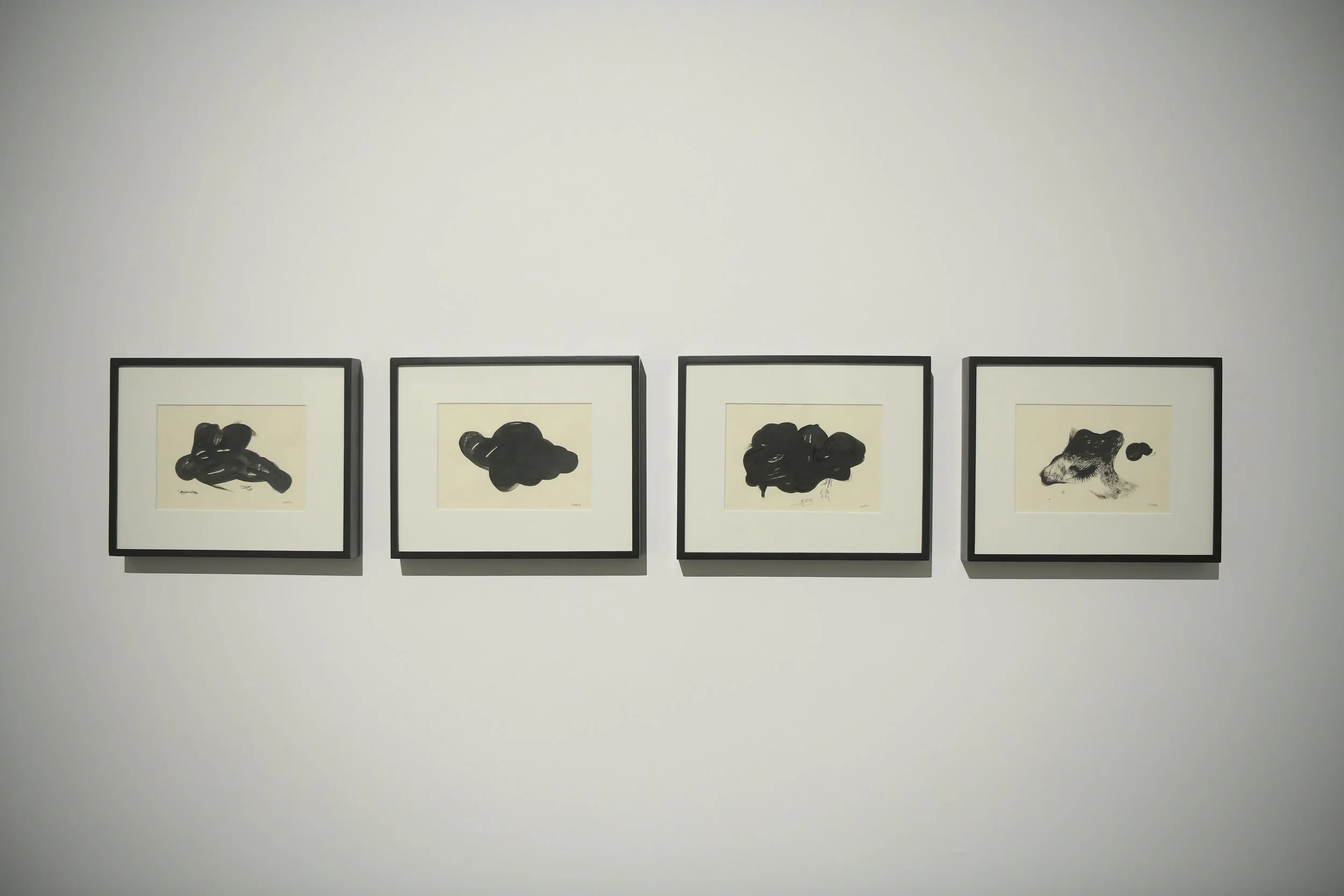

Jeram Patel’s ink on paper. Image courtesy: Gallery Espace

Similarly, curatorial engagement in India has become a cumbersome promotional exercise, where most such interventions are limited by presentational tactics or imbued in discourses on space and architecture (which was initially driven by the likes of Ashish Rajadhyakhsha and Vivan Sundaram in the late 1970s). The fact that most (if not all) curatorial interventions account advertorial stances, “Ink” posits itself on the ongoing critical interventions on ‘materiality’ and studio practices.

The show includes artworks by the likes of Sonia Khurana, M. F. Hussain, Mekhala Bahl, Amitava Das, Jeram Patel, Gautam Bhatia, Manu Parekh, Partha Pratim Deb, Dilip Ranade, and Madhvi Parekh. “Ink” brings forward an insight into the artists’ lives, the artworks, and the stages of art-making. In a manner of speaking, the show performs the difficult task of visualising dialogues on (re)presentation(s) while also portraying sketches and ink works placed outside conflicts of ‘finality’. The curatorial note touches upon the history of ink in art-making, but leaves its viewers to disengage with its history and actively engage with a display of practice and styles.

The fact that most (if not all) curatorial interventions account advertorial stances, “Ink” posits itself on the ongoing critical interventions on ‘materiality’ and studio practices.

It is pertinent to note that these styles also observe absolution through their presence at the venue, where we are made to witness the linearity in practice against the idiomatic practices of art. This becomes evident when we look at Gautam Bhatia’s paperworks placed against grey walls. These works can be seen as planned and designed. The impacts are definitive on a viewer looking to employ the practice of arrangements to their visual contacts. Once again, one can be certain that Bhatia’s practice contains itself in the aesthetics of visual strategies.

Similarly, Madhvi Parekh’s two wide paperworks were staged close against a grey wall, where we could witness another genre of play with compositions. While most people have different readings of the nose featured in her compositions, I have always maintained an understanding that the nose alludes to the phallic, and that it being placed on the face depicts masculine prowess and pride. To expound on my observation, I posit that the artists in this show were presented in their barest styles, where even the likes of Manu Parekh’s work was staged at a preliminary account to his oeuvre. The peeling of each layer involved in art-making is set at the layer where foundations are laid, or where the artist sets pen(cil) on paper, or, perhaps, any flat-surface to lay out an intelligent strategy for visual articulation.

M.F. Husain’s ink on paper. Image courtesy: Gallery Espace

Gupta’s curatorial gaze picks on this preliminary account of art-making as a spatial location for artworks to breathe in the public eye. Her intervention was based on a favouring eye, where the artworks were picked on the basis of impact, and without any planned proposition of ideas. According to her, studios are interesting spaces to locate an artist’s methods where nooks-and-corners of the space harbour mysterious or intricate details of their personalities. In this venture, she looks at the laying of an artist’s initial methods, where several attempts are cast aside before a line sits well for the next phase of treatments, until it reaches its final stage.

The display proposes an interesting spatial engagement with the negative and the positive space on a canvas. A lot of blank spaces were placed on the walls between artists’ works and to set aside a body of work (certain artworks were staged as bodies that performed their tasks in diptychs or triptychs). Partha Pratim Deb’s works had three series staged in diptychs and triptychs that worked with the idea of movements and patterns. His pieces deliberately portray repeated patterns while it dabbled with monochromatic colour palettes with a sudden dash of bright colours. These artworks were staged inside a corner-like space within the gallery to segregate its affectations from the next corner-like structure, which featured the works of Amitava Das, Madhvi Parekh, and Dilip Ranade.

Amitava Das’ contribution to the show becomes fairly climactic, where we see his artworks placed in separate sections, binding the visual narrative and language of the show. The position his artworks hold is beyond the mere idea of the preliminary or the linear. In fact, he projects ambiguity and harmony through his malleable (but boldly) distorted imagery. Lines run through them in such measured metres that these images begin to merge the obviously disjointed line of thoughts of the other artworks at the show.

Again, Dilip Ranade too perforates the practice of arrangements by projecting (un)finished figures. Most of his figures are distorted at their necks where scribbled lines would fall towards the lower part of the artwork. Ranade’s work has a strong sense of direction, where these images cannot be staged in any other way, which aids the show in finding a balance between the other artworks.

The exhibition places M. F. Hussain’s works at the entrance, facing artwork by Sonia Khurana. I felt that this choice comes across as an important statement of time and timelessness. Khurana’s (mostly acknowledged for her performance art) work is a testament on her practice, where she projects the body in motion in her paperworks. Hussain’s art, meanwhile, speaks of a perfect language that has become intrinsic to South Asian art history, and yet, remains fresh to its viewers.

Parta Pratim Deb’s ink on paper works. Image courtesy: Gallery Espace

The space is also shared by paperworks by Mekhala Bahl (mixed-media) and Jeram Patel (ink on paper), stitched together in another section that ran into the basement. Bahl’s works are laden with grave colours, patterns, and designs and they made a prominent presence in this group of artworks framing intricate details and narratives. Simultaneously, Patel’s body of work projected a thoughtful gesture embedded in his practice, where each form was blending into a mesh and was in the process of ‘becoming’. Given the fact that Patel’s practice is a concluded one and his works were staged on the walls of the staircase leading to the basement, Patel’s art conveyed a sense of humour of binding and moving to the next section of the show.

I found that the exhibition raises questions and occupies positions on the de-schooling of art-practices, and the role of art shows. “Ink” plays the role of a catalyst in thinking beyond the normative practices of art-making, art showcasing, and curatorial interventions. Gupta may not have planned her interventions in the manner of my reading, but she has set the tone on looking beyond the periphery of art and curatorial practices.

***

Satarupa Bhattacharya is an independent cultural practitioner, associated with academic journals on visual and cultural studies. She is currently working on academic publications and a novella. You can find her on Instagram: @sattybatty.