THE MENDICANT PRINCE: A Women-centric retelling of the Bhawal Sannyasi Case

In her latest work, Aruna Chakravarti revisits the early 20th century ‘mejo kumar’ story, now allowing all its characters—particularly its females—to speak in their own voices.

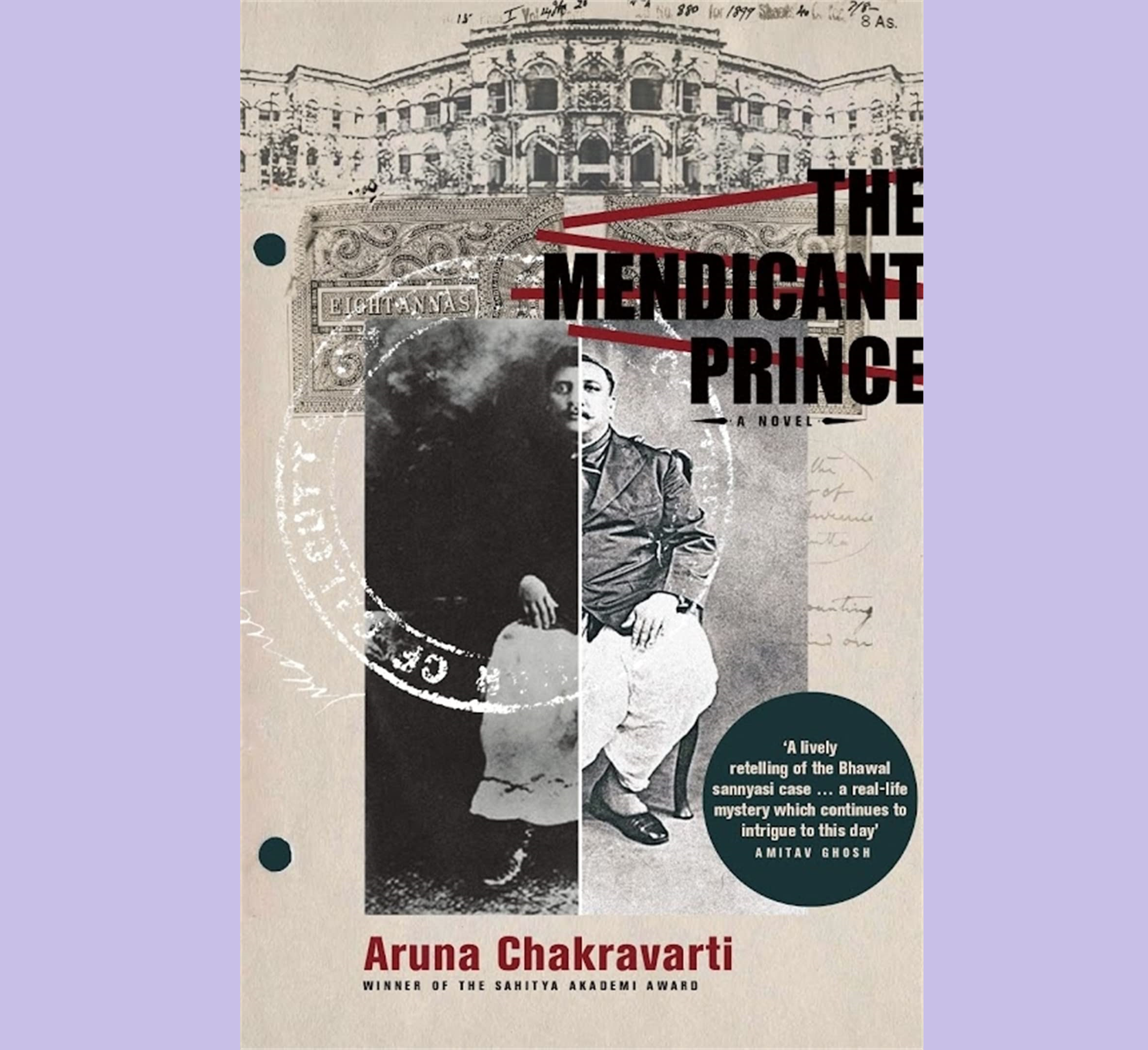

In The Mendicant Prince (Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan, 2022), Sahitya Akademi Award-winning writer Aruna Chakravarti retells the story of the Bhawal Sannyasi case. In 1909, Ramendranarayan Roy, the second prince of the Bhawal estate in the eastern part of the undivided Bengal, died, despite no fatal disease ailing him. Known as ‘mejo kumar’, he had been in Darjeeling at the time, where he’d gone to treat his syphilis. But his death was hotly debated among the tenants of the Bhawal estate. While a few wondered whether Roy’s body was cremated properly, as per customs, many even doubted his death.

And then, twelve years later, a sannyasi (ascetic)—a lookalike of mejo kumar—visits the estate… and everybody goes a tad bit crazy. The ascetic, who initially refused to identify himself as the second prince, eventually confesses that he is indeed Ramendranarayan Roy.

This, however, raised several questions: Where had he been all these years? What had he been up to? Is he an imposter, trying to get hold of all the perks—the land and the estate—now that none of the other princes are alive to contest his claims?

While the Rajbari was bustling with a renewed energy, neck-deep in dilemma, mejo kumar’s reappearance made the Britishers most uncomfortable. They wanted to ascertain the identity of this sannyasi as soon as possible for the gains of their own enterprise, and this quest led to the beginning of one of the most well-known, widely debated, and covered legal battles in British-ruled India.

In this regard, as everything about the case is, as they say, ‘an open book’, it’s fitting to enquire about the need to fictionalise the story. In an email conversation, Chakravarti tells me that, “The compulsion to retell the story came from the urgings of some friends who are distant relatives of the Bhawals.”

She further adds, “I had already written two fictional family histories. The first The Inheritors was an account, encompassing three generations, of the lives as lived by my foremothers in an obscure Bengal village. The second, Jorasanko and its sequel Daughters of Jorasanko, attempted to look at the lives of the Tagore women from within. Both were fictional interpretations of known and documented facts. My friends, who are also my readers, suggested that I carry out the same sort of exercise with the Bhawal family. I hesitated a bit, then agreed.”

Chakravarti creates a unique landscape of the time, of a world that existed over a century ago, so poignantly that it feels that one is reading the story of one’s own neighbourhood.

It was, however, Chakravarti’s innate desire to render voice and exhume the bodies of the invisibilised people of the Bhawal Sannyasi story: its women. She tells me that the “only justification of retelling a known story” was to “allow its characters, particularly its females, to speak in their own voices”. And that’s one of the most definitive qualities of the Mendicant Prince.

It’s a sheer joy to re-access the Bhawal Sannyasi case from multiple perspectives. The three sisters, the tenants of the Bhawal estate, and the daughters-in-law of the Rajbari—all find a dedicated chapter for them to narrate the story as they deem fit. This exercise not only makes the narrative enriching and layered, but also makes reading this book a thoroughly absorbing experience.

Chakravarti creates a unique landscape of the time, of a world that existed over a century ago, so poignantly that it feels that one is reading the story of one’s own neighbourhood. Here’s how Chakravarti begins the story in January 1921 when locals “near the Buckland Bund, an embankment on the Buriganga river” find their curiosity piquing at seeing this person “sitting cross-legged on the Bund, gazing into the distance day and night, for the past three months, impervious to the cold gusts of wind and spray that rose from the agitated waters below.”

They suspect him to be the second prince of the Bhawal estate. As both his brothers had long died and the princesses had thought it fit to chart their own individual paths, and with the rise of British intervention, perhaps the people felt that what they had lost had reappeared, which is why they placed tremendous value in this rediscovery of a Raja who had died over a decade ago.

The accounts of his death differed though based on who was telling them. “Doubts [were] being cast on the validity of the cremation in Darjeeling” and what nobody seemed to come to terms with was the fact that mejo kumar wasn’t deathly sick. But Rajbari couldn’t entertain any false stories or theories. Baro kumar—mejo kumar’s elder brother—decided to nip the rumours in the bud and sort of legitimised his brother’s death by performing shraddha, despite disapproval from the pundits.

Here, the book introduces its readers to the three sisters of the princes, who were by all means more competent than their ill-informed and vice-laden brothers.

There was Indumayi—the eldest—who, though deeply affected by her brother’s death, was determined to quash any rumour around mejo kumar. “While what you have just told is very disturbing, I refuse to equate my brother, a prince of the realm, with a grass doll,” she says. “It is demeaning not only to his memory but to the prestige of the Rajbari.”

Indumayi was sure of some foul play that had led to her brother’s death. In the book, she reckons that Satyendranath Banerjee—the brother of mejo kumar’s first wife Bibhavati—has a role to play. It’s telling of Indumayi’s character in the way she tackles this situation; each decision she makes renders a distinct complexity to her character.

“The women of Bhawal were impacted by the events—physically, emotionally, and financially—in a much more powerful way than the men,” Chakravarti tells me. “Barring mejo kumar, of course. Yet the documented evidence I studied did not provide a single hint as to how they had reacted, what they had thought, and how they had come to terms with a completely altered way of living. I thought I would regale my readers with an imagined reconstruction of their lives, and I did so.”

And it’s the grief-stricken Bibhavati who proves to be a far more complicated character than one is tempted to believe from the well-known story. This imagined reconstruction makes the reading of Bibhavati’s brother particularly interesting. “He expected absolute obedience in return for his love,” Chakravarti notes, regarding the love Bibhavati’s brother had for her, “a loyalty that bordered on slavish devotion. The slightest murmur of dissent on my part would shatter the glass. It was that fragile.”

While Bibhavati didn’t receive the husbandly love, it was in Darjeeling that she gets to know a thing or two about her husband, and his actual feelings towards her. It is clearer that mejo kumar had not granted her the respect and dignity she deserved. However, as fate would have it, she lost him just as she was beginning to accept their relationship.

Although she surrendered to everything her brother demanded of her, here’s what she notes particularly about mejo kumar: “It’s a funny thing to say but I was convinced that he went to other women as a matter of habit. Not because he wanted to. Because, in some strange way, he felt he owed it to them. But I was the one on whom he depended. I was the one he truly loved.”

For Bibhavati, who didn’t come from an affluent family, a riches-to-rags story follows right after mejo kumar’s death. But the appearance of the ascetic—claiming to be her husband—failed to excite her, as she had her back turned towards her past. Despite what she was told or informed, she kept a firm stand. The ascetic, she believed, was an imposter.

“The persons who were impacted most by this case, particularly the women, are just names in letters and documents. Adding a fictional component to already known facts enabled me to imagine the kind of lives they may have lived; the kind of people they may have been.”

This is one of the principal conflicts that drive this story, which is interspersed by a variety of viewpoints, especially that of its outsiders like Taufique Ali and Kashinath Hazra—both tenants at the Bhawal estate. Theirs are observations that are striking, for these characters don’t have any stakes in the larger scheme of things.

Reading such varied perspectives made me wonder if there was any research material that could signal that the women and the tenants in this tale had such distinct voices. “No”, says Chakravarti. “I did not come across these voices during my research. In fact, they were just names; nothing more. The characters of the women are totally imagined. They have been given different backgrounds, different ages, and different personalities and so their viewpoints are, quite naturally, different from one another.”

The book also features excerpts from the legal communication between the manager(s) of the Bhawal estate and the British district collectors and magistrates, letters to the editor, letters from the grandmother to Bibhavati, documents, judgments, etc. All this renders a nonfictional flavour to the narrative.

“Most of the documentary evidence such as letters, newspaper reports, official communications, medical opinions, and details of the mejo kumar’s physique, as per the records of the Insurance Company, that have been cited in this book are original,” Chakravarti tells me. “So are the judgements. The cross-examinations that took place in the Dhaka District Court are also largely based on data but not wholly so. Some liberties have been taken there. The personality of the District Judge, Pannalal Basu, and the process by which he arrived at his findings are totally imagined.”

“The story of the Bhawal Sannyasi, including the details of the legal case that followed, is known by most Bengalis,” adds Chakravarti. But, “the persons who were impacted most by this case, particularly the women, are just names in letters and documents. Adding a fictional component to already known facts enabled me to imagine the kind of lives they may have lived; the kind of people they may have been.”

“I enjoyed the liberty of giving them distinctive personalities and characteristics, loves and hates, dreams and aspirations, joys and sufferings,” says Chakravarti. “Carrying out this exercise was almost like creating my own characters.”

And it’s this joy that the author shares with me, any of her readers, including me, experiences reading this book where women play a significant role in the overall narrative, unlike the documented history of the well-known case. By centralizing their experiences in The Mendicant Prince, Chakravarti not only emancipates them but also corrects the erasure of their voices from the storytelling tradition—oral or written.

***

Saurabh Sharma is a reader and a writer. He works as a writer in an IT research and advisory firm in Gurgaon. He reviews books and pretends to write on weekends. You can find him on Instagram: @writerly_life and Twitter: @writerly_life.