Hanging on to the Trapeze

Rambo Circus troupe at the shooting of their show Life Is A Circus

The pandemic threatens to be the last nail in the coffin for many of India’s great circus troupes. By taking their act online, Rambo Circus hopes to keep an acrobatic balance for the show to go on.

In the age of multiplexes, amusement parks, concerts and celebrity plays, it might seem that Sujit Dilip and Biju Pushkaran are stuck in the past. But the circus, they say, is their life.

“I ran away from my home in Kerala after my father beat me up,” said Pushkaran. “I hid under a train seat and fell asleep. By the time I woke up hungry, I had reached Bombay.” A family brought some food for a crying Pushkaran and took him to their home. One evening, on the pretext of finding him a job, they took ₹220 from him, all that he had, leaving him on the road, alone and hungry. He started roaming the city till he strayed into a circus tent near a railway station—and stayed. He was 10 years old

“I spotted men wearing holy markings on their head as people in Kerala do. So, I said in Malayalee, ‘I am hungry’. They gave me food and shelter and asked me to serve tea and snacks to the artists in return.” Over the years, he worked with different circuses and rose the ranks of a helper, a manager, a publicist and the head clown. He was even invited to perform at The Monte-Carlo International Circus Festival last year but sadly, he didn’t have his passport ready. “The circus has given me love and respect,” the 50-year-old contends.

As for Dilip (45), he has the tall task to keep the legacy of Rambo Circus alive, which his father PT Dilip founded in the year 1991. The roots of Rambo Circus, however, are even older; it was formed when three Kerala circuses—Erina Circus, Victoria Circus and the 80+ year old Oriental Circus—were bought together. “The owners wanted to sell these circuses as they were making losses. My father bought them and he got 300 artists and many lions, dogs, horses, camels, elephants, tigers and chimpanzees in the deal. He named it Rambo Circus,” Dilip recounts. His father, he says, pronounced Rambo as Ram-bhaw, where bhaw means ‘brother’ in Marathi.

Dilip took over the reins as the proprietor of Rambo Circus when he was just 19. “My father suffered a heart attack while doing shows in the Gulf countries. I had to leave my college studies mid-way.” But being a science student, he was able to bring hydraulics, pneumatics and other technical upgrades to the circus, which would draw up to 4,000 people per show during the peak season. Rambo Circus was also the first Indian troupe to hold an indoor show, at Mumbai Prithvi’s theatre in 2012. “Barring the 60 days or so that we spent travelling from Rajasthan till Andhra, we’d perform every day.”

A still from the filming of Life Is A Circus

*

The obituary of the Indian circus has been written often: It is dying, it will die, it’s already dead. But that hasn’t broken the spirit of Rambo Circus yet. In the past few weeks, it’s managed to do what no other desi circus has done and also prove to naysayers in some measure, that there is space for the circus in the modern world, alongside TV channels, OTT shows and social media.

On September 25, Rambo Circus took its first show called Life Is A Circus - online. It wasn’t a livestream show. It was, instead, scripted, rehearsed, recorded and edited, squeezing into an hour the journey of ‘Rambo’, the struggles faced by other Indian troupes, and a tribute to the frontline workers of COVID-19.

The online show includes most of the Rambo Circus favourites—trapeze flying, ladder balance, juggling balls, stilt walking, and silly clowns—but the daring ‘Wheel of Death’ and trampoline acrobats were left out, because specialised performers had gone back home due to the pandemic and weren’t available for the shooting in August. Mumbai rains made the job for the circus performers tougher, but they plodded on.

“We didn’t shoot in a studio but on ground. The rainwater flooded our set and we had to postpone the shoot,” said Dilip. Despite the hurdles, the ticketed show, which ran for eight slots from September 25 to 27 on bookmyshow.com, was a sell-out. So much so that it had to be brought back on popular demand and it will now run every weekend up till Dussehra. “The demand for weekdays shows have come in too.”

Each screening is followed by a short meet-and-greet with the man behind the golden wig, red bulbous nose, oversized costume and tiny hat. The elated clown is Pushkaran, who shares snippets from his chat with kids, who were sometimes accompanied with grandparents, “They wanted to know what circus artists eat, where we live, how our families are coping with the pandemic. They said they miss going to the circus.”

The obituary of the Indian circus has been written often: It is dying, it will die, it’s already dead. But that hasn’t broken the spirit of Rambo Circus yet. In the past few weeks, it’s managed to do what no other desi circus has done and also prove to naysayers in some measure, that there is space for the circus in the modern world, alongside TV channels, OTT shows and social media.

Life Is A Circus was not exactly conceptualised to adapt to the ‘new normal’ and go digital like everything else. It started as a crutch for survival, an initiative to raise funds for the 100 cast and crew of the Rambo Circus, who have been out of job since the lockdown grounded them in the Airoli neighbourhood in Navi Mumbai.

With the exception of Diwali, summer is usually the peak season for the circus business; Rambo Circus had arrived in Mumbai to do shows in March, and they have been stuck in the area since, staying under a tent they have pitched on a ground, along with 17 dogs and a pony. Forty members of the traveling circus did return to their respective hometowns, but they remain out of income—just like the ones who stayed put in Mumbai.

Pushkaran says the pandemic has been the lowest low of his life. “I haven’t held a note of ₹500 in months.”

*

First, there was the satellite TV in the 1990s; then, the ban on the use of wild animals in 1997; child labour was banned in 2016; and then, grounds for performance in Indian cities shrank and shrank; all bringing Indian circus to its knees. As a result, circus troupes in India dwindled from close to 300 in the 1990s to just 30 in 2013, some reports suggest. Demonetisation in 2016 ravaged the profession further, and now, the pandemic has brought this travelling livelihood to a grinding halt.

“If we don’t support these artists now, they will be forced to look for jobs elsewhere,” said Dilip. “We would be left with only eight or nine circuses in India by the end of 2020.”

Biju Pushkaran, head clown at Rambo Circus

The circus tradition goes 140 years back in time, and it’s an art form—a form of theatre—that far predates our cinema culture. The Great Bombay Circus turned 100 this year before calling it an innings; their owner decided to shut the show in the wake of falling audience and unsustainable cost of operations. Even the world’s biggest circus producer, Canada’s Cirque du Soleil, filed for bankruptcy protection and furloughed many performers to stay afloat in the post-COVID world.

Rambo Circus, like the rest, has had it rough. “I have sold two of my flats to finance my circus - one post the demonetisation in 2016 and the second after floods damaged our tents and lights last year,” shares Dilip. Since the pandemic, he says that just the daily expenses of feeding his artists, tentmakers, technicians, cooks, their families and animals is ₹25,000. Rambo Circus hasn’t made a single paisa since March.

“It’s all thanks to our well-wishers,” Dilip shares. NGOs, local politicians and Gurudwaras have assisted them with food packets and dry ration. As the word about their plight continues to spread, a cancer trust donated ₹50,000, while a government official gave ₹30,000 from her pension. And when Dilip and his own family members contracted coronavirus, Aditya Shah from Bengaluru, whose family has been sponsoring circuses for over 70 years, and his friend Suganthan Asokan from Mumbai, stepped in. They raised over ₹12 lakhs for Rambo Circus through a crowdfunding campaign.

“Even (industrialist) Anand Mahindra and (actress) Renuka Shahne has made donations of ₹3.15 lakh and ₹51,000 each,” said Dilip. “Honestly, as much as our circus artists are grateful to all the donors, they are feeling embarrassed too. They ask me, ‘How can we use this money? We haven’t earned it by performing’.”

So, when the folks at Laqshya Live Experiences suggested doing a fundraiser show instead, it just clicked. “Life Is A Circus is not a typical Rambo Circus show. It’s like a play, with lots of lights, circus acts and narration. It’s a story of the ups and downs that Indian circuses like ours have endured to survive.”

Shooting for the show made Pushkaran feel like a fish out of water. “I could not give a shot for the first two hours because I have never performed without an audience. Spontaneity, audience interaction, laughs and claps is what makes a circus come alive.” While he says nothing will come close to the charm of a live show, he is excited to explore the possibilities that lie behind the digital door. “I will do anything to keep the circus going,” he says.

*

The real draw was, of course, the animals: juice-drinking chimpanzees, cycle-riding elephants, stunt lions, and jumping dogs who did what the ringmaster commanded.

“I know a lot of people feel circuses abuse and mistreat animals but if had social media that time, I would have shown the real picture,” Dilip adds in an emotional voice. “Living in the circus was like living in a jungle in a big village. I used to sleep besides four-five lions. They used to lick my face in frolic. A small elephant would take my blanket away and pour water on me at 6 AM every day. One horse had a liking for cold drinks. One chimpanzee would jump with joy every time Hanuman appeared on the TV show Ramayana. Those were golden days.”

No stone was left unturned in the upkeep of the animals, he claims. “We got dental fillings done for tigers and lions, which was unheard at that time.”

But the continued campaign against the use of wild animals in circuses came to a head in 1997 and the circuses crashed. “We lost our biggest audience—the villagers. They would come only to watch animals as they didn’t have a zoo in their area,” Dilip says.

His business interest aside, I ask Dilip if he believed that taming animals for human entertainment is cruel? He doesn’t give a clear answer, but feels that the circus owners should get a fair chance to prove they don’t abuse animals. “I had attended a conference by Federation Mondiale du Cirque in Monaco in 2009. A study discussed there claimed that animals in circuses tend to be less stressed than in jungles because their food and ageing needs are taken care of.” However, I could find no such study online.

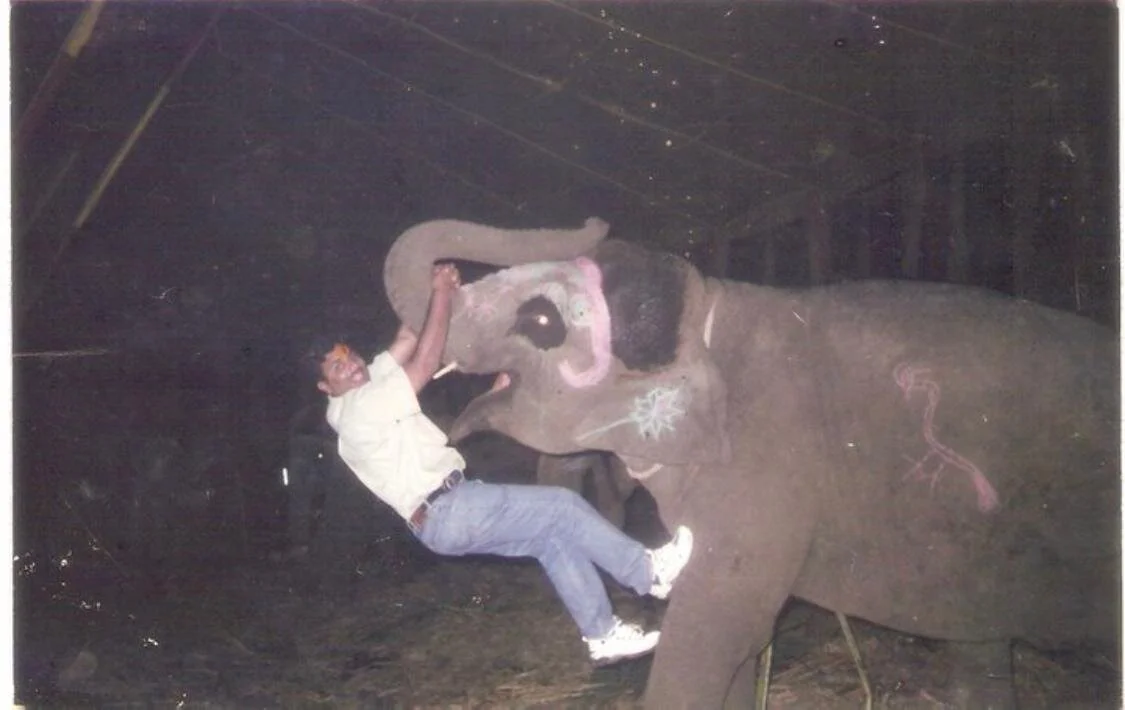

Old photo of Sujit Dilip, seen here playing with Nidya, the circus elephant

The next ‘blow’ for Dilip’s business was the ban on the employment of children under 14, and he lost a lot of young performers. In 2016, Dilip wrote a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to help save the Indian circuses, and argued that, for those who wish to pursue circus gymnastics, the training must start young.

*

These setbacks have thinned the circus calendar out to weekend shows, with fewer slots and more empty chairs. “The biggest challenge is to get people off their phone and come and watch a live show,” Dilip says. “Earlier we’d paste one pamphlet on the wall and thousands would show up but now even spending lakhs in advertising doesn’t help.” Still, Dilip isn’t ready to accept the obituary of the Indian circus. “Look at our online show. Young and old, the audience for the circus is definitely there. All we need is government recognition and funds to level up to the standard of international circuses.”

As time runs out, Dilip has upped his efforts. “We are going animal-free in the future shows,” he reveals. Plus, according to reports, a Moscow-based company has agreed to upgrade the circus routines, an Italian firm will redesign the seating arrangement, and a German company will introduce hologram and mechanical animals for Rambo Circus.

“It’s wise,” he says, “to move with the times.”

***

Barkha Kumari is a freelance journalist and a lucid dream blogger from Bangalore. You can follow her on Twitter: @Barkha2803 and Instagram: @rainsnroses.