Stepsons and Foreigners: An Interview with Aruni Kashyap

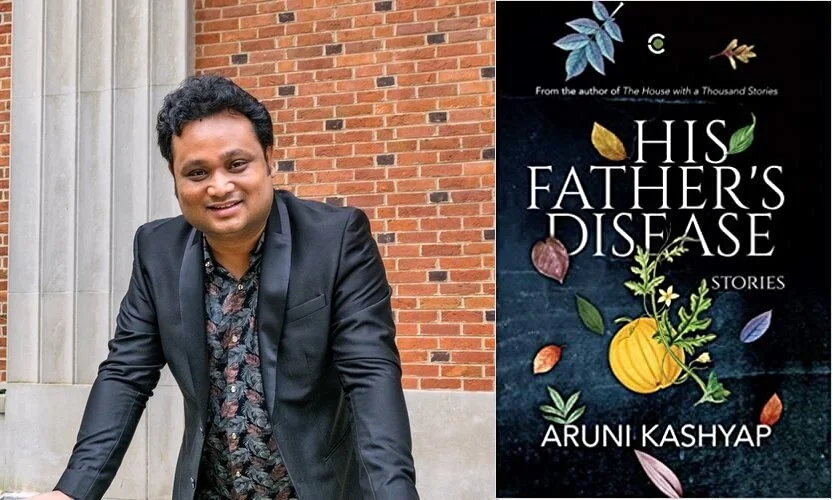

Writer, translator, and editor Aruni Kashyap discusses his remarkable short-story collection His Father’s Disease, building the shaky bridge from Assam to Delhi to America, and the indissoluble bond between the personal and the political in literature.

Reading the opening story “Skylark Girl” of Aruni Kashyap’s 2019 collection His Father’s Disease, one can’t help but feel that we have been presented with an almost impossible jigsaw puzzle set, where the pieces aren’t cut to fit each other, and yet, a broader, beautiful picture somehow promises to unravel as we reach the end. Like much of Kashyap’s work, this story is a meditation on things lost in translation, of those badly-fitted jigsaw pieces.

“Skylark Girl” is about Sanjib, a writer from Assam who has been invited to a conference in Delhi to read a translation of his Assamese story in English. The social pressure of English-speakers stresses Sanjib, and many of the attendees expect him to read a story that will be a response to their idea of Assam—insurgency, violence, tragedy—instead of the tale that he is actually there to tell. Sanjib reimagines a folk fable of Tejimola, the woman who refuses to die, reappearing in new forms in nature. Translations, if you will.

There is this sense of ‘translation’ throughout Kashyap ten-story collection. Every character is an outsider to the world around them: a homosexual man in his village in Assam, an Assamese in New Delhi, an Assamese in America, an inter-racial couple in the home of a conservative American family, and so on. The stories present characters that exist without that perfect jigsaw fit, of a world where we are always left with a sense of unfinished, of new questions to answer even after the story is long finished.

Kashyap’s work has always foremost confronted his Assamese identity, both in the social constructs of Assam, and of the cultural clashes with ‘mainland’ India, or abroad. His first novel The House of a Thousand Stories was published in 2013 to high critical acclaim. Over the years, he has also edited the short-story anthology How to Tell A Story About an Insurgency by various authors, translated Indira Goswami’s novel The Bronze Sword of Thengphakhri Tehsildar, and published fiction in Assamese, including the 2018 novel Noikhon Etia Duroit.

Kashyap now works at the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, where he is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing. He joined The Chakkar this week to talk about His Father’s Disease, the ‘otherness’ of Assamese identities in India and the USA, the writers who most influenced him, and the indissoluble bond of the personal and the political in literature.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Chakkar: The first story ‘Skylark Girl’ laid out the pieces for the collection, giving us a sense of alienation. It features an Assamese writer in Delhi, who feels like an outsider. This ends up being an underlying theme in the rest of the collection, of people feeling like outsiders, whether it is people of the same culture, whether the main character is a homosexual, or an Indian in the US, or someone who can’t speak English well in an English-speaking environment. Was the ordering of the collection purposeful, in starting with this story?

Kashyap: That is a very pertinent observation. I think all of the main characters in the collection are outsiders in some way or the other. One of the reasons why is that they’re from the Northeast in India. There is no community for them as migrants abroad. For example, Gujaratis can find their people in Africa, England, America, Canada… Gujaratiness is already established in these spaces. But what does it mean when you come from a community where there has been so little migration from their spaces?

And some of the characters are even outsiders in their most comfortable space, which is their home or their village, such as the character Anil (from “His Father’s Disease”).

I actually placed “Skylark Girl” in the beginning deliberately to serve as a courtyard, as a conversation-framer of the collection. It was a deliberate act, because I wanted the readers to know why these stories are valuable. There is so little information about cultural productions or literary expressions from the Northeast, that we are not seen as valuable people who can produce valuable stuff. How do I engineer that conversation? As a writer, I wanted to do that, so the next writer who comes from the Northeast after me won’t have to do it.

There are things in my stories that are unresolved. Unresolved trauma and questions. And this is what life is. I’m more interested in the absolute wonderful possibilities of human beings, and how interesting they are, and how problematic they are, and how contradictory they are. That is what is interesting to me as a fiction writer.

In order to begin, shape and frame a conversation about the Northeast, I not only have to begin with a story like “Skylark Girl”, which is a deeply metaphorical story and a folk story, but I also have to talk about my work a lot. You’ll see that in international literature, someone like Toni Morrison having to talk a lot about her work. But Philip Roth never really talks about his literary traditions where he comes from, because he doesn’t need to. There are enough people from his community; there have been thousands of novels about New Jersey. But for Morrison, it was very different—and she had to talk about how she is using Black aesthetics.

I think this is the editorial and intellectual labour that anyone coming from the underrepresented space has to do, which I have to do. It’s why I had to put “Skylark Girl” first. In fact, I re-wrote “Skylark Girl” for this collection; it was originally published only as a folktale retelling, but I created the character of Sanjib who reflected so many of my experiences of being a writer over the past 10 years.

TC: You mentioned writers who, beyond their work, have had to represent their culture, too. As an Indian in the US, there is always that ‘double consciousness’, that comes with being any minority. What I found even more intriguing in your work that there was an added layer of consciousness: you’re trying to tie in Indian writing for the Western audience, but also, Assamese writing and tradition for the so-called ‘mainland’ Indian audience. There are several hurdles of representation that you’ve had to cross. Do you feel that pressure in your work? Do you feel that you have to check all these boxes to tell a story?

Kashyap: I used to feel this way 6-7 years ago, when I wrote my first novel (The House with a Thousand Stories). In my early draft, I realised that I was trying to represent my community, my history, and my politics so much that the story had taken a back-stage. I wrote another draft and I removed these references. There is a lot of politics in the book, but I stopped trying to tell the story of the state. I only told the story of the characters. Because I’m not a historian, I’m not a sociologist, I’m a storyteller. And storytelling means that I have to tell the stories through characters. And if somebody is interested [in the history and politics], they can always go and read up.

For example, after reading James Baldwin, I got interested in African American literature and politics. I started reading more about African American history, discrimination and politics. And I learned more. But James Baldwin wasn’t trying to tell me the entire history of African American people; what he told me is what it means to be an African American writer and a person. And what it means to come from this community.

I think that it is not my burden to represent Assam—and forget about representing India or Delhi—for the American or any audience. Because the audience will change the texture of the text, and change it to a certain kind of text that I don’t want to write. The texts that I’m inspired by are written by Nirmal Verma, Mahadavi Verma, Ashapurna Devi, Vaikom Muhammad Basheer… These are the writers I grew up reading. They were not going to explain the historical, sociological, or cultural realities to anyone. This is not about being smug; it’s about choosing a kind of literary aesthetics and doesn’t require explanation, that makes a reader an active participant, that makes them google or look at an encyclopedia.

I’m also interested in writing only literary fiction, which means that, whoever wants to pick up my book will need to do a little bit of work. I think that is the nature of fiction.

I think it’s good that a book can start a conversation between two people, because it will bring in a third person and a fourth person. Unlike, say, a commercial novel that answers all questions and explains everything, because their goal is to reach the widest audience. My goal is to do that, too; I want to sell a lot of books, but I want to do it on my own terms.

I keep joking: the burden of representing Assam is on Priyanka Chopra, because she got 15 crore rupees to appear for 30 seconds [to promote Assam tourism]. That, too, in a studio, not even in Assam. Give me one crore and I’ll probably do it. I’ll appear for one hour.

TC: What I’ve noticed in your stories that, the short-story form feels very contemporary American to me. Every story concluded with more questions and answers. There was more of an emotion rather than a clear resolution. Is that something that’s part of the Assamese tradition of storytelling too, or is that an influence on you from American fiction?

Kashyap: I think Americans do write very good short stories. It’s a different thing how political or socially-engaged their work is; that’s a different conversation altogether. I’m deeply influenced by American literature. It was my favourite course in college. Some of my greatest mentors—meaning the writers whose work I read to become a better writer—are American writers, like William Faulkner, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, or Louise Erdrich. Erdrich in particular, because she was tribal like me. Coming from the Northeast, my indigenous identity has been very important to me, and Edrich in some way gave me literary permission. So, it is no surprise that you see influences of American literature and American short stories in my writing—I’m very proud of that.

But I’d also say that there is a very strong short story writing tradition in Assamese and Bengali, which are the other literary cultures that I grew up reading. I learned much from Tagore about the sense of an ending, where there are still questions in the end. Tagore used to say of short stories, “Shesh hoye hoilo na shesh”, which means that “The story ended, yet it did not”.

TC: Did you write these stories over a long period of time? Did you feel your narrative voice changing over time, or were you able to keep some consistency for the collection?

Kashyap: I wrote ‘His Father’s Disease’ and ‘Skylark Girl’ in 2010 and in 2011. Rest of them I wrote after 2015. Within these 10 years, I wrote a lot of stories, I think I have 30-40 short stories, but only 10 made it to the collection.

I think that [the narrative] changed. I wasn’t trying got keep any consistency. I think I’m growing as a person, a writer, and an artist. So, I think that’s a good thing. Earlier on, I used to write more instinctively, because that’s how I knew how to write. But teaching creative writing has made me more aware of the craft. I try to sustain the interest of the reader much more. I hope that my voice and style have changed for the better.

TC: Something that I appreciated about these stories is that the narrative voice was very non-judgemental. The narrator wasn’t telling me how to feel. The feelings were coming from within myself; if I was a different type of person, I would have taken something completely different from these stories. Do you think about the reader when you have this voice, or about what you want the reader to take away from your stories? Or do you distance yourself from the readers’ emotion or reception?

Kashyap: I try to capture what I see. In the current neo-liberal conversation about literature, people say what should be, and I don’t think I’ve gained the experience enough to say what should be. So, I just write the way it is.

There are things in my stories that are unresolved. Unresolved trauma and questions. And this is what life is. I’m more interested in the absolute wonderful possibilities of human beings, and how interesting they are, and how problematic they are, and how contradictory they are. That is what is interesting to me as a fiction writer.

Most of the time the authorial intention is very dormant, but I’m letting my characters move around naturally and improvise on stage. I’m one of those writers who actually writes a lot of stories from actual events. So, the Anil story (“His Father’s Disease”) actually happened in our village. Obviously, I’ve dramatised it. “For the Greater Common Good” is about my own family, because my father’s elder brother was a sorcerer. He practiced healing sorcery. And these are events from my childhood. “Before the Bullet” happened in a friend’s village. There are some things in “Before a Bullet” in my reading and research of the events that was so traumatic that I didn’t want to include in the story, because I felt that people will not believe it.

There is so much richness in what has already happened, in the way things have happened, that I don’t want to pass any judgement.

TC: You do a great job of linking the personal with the political, where the political usually stays in the background. One can appreciate the story for only the personal—but the political adds a whole layer of wonderful complexity.

Kashyap: Because you’re Indian, you’re from India, so you may understand what is going on. Someone not from India might not be able to understand [the political layers], and that is okay, too.

TC: In contemporary times, the political divisions feel wider to me. Do you feel that this relationship between the personal and political is more crucial than ever? Or, would you say that it’s always been this way, and it’s only now that many who have been in places of privilege are feeling the effects of politics more than they have in the past?

Kashyap: You’ve answered the question very beautifully—and I’ve written about this in my satirical essay called “How to Write about Northeast India”.

Growing up in Assam, the Indian state was always very brutal. You could not separate the personal and the political—it was all political. In teaching my students here, I used a writer from a deeply politically fraught place, and people have said to me that this fiction is ‘agenda-driven’ because of the many references to politics. But the fact is that, in countries where the political system has failed the welfare of people, the people are concerned. It effects their daily life. How do we not talk about politics? How do we separate the personal and the political?

The Indian state has been practicing brutalities in the margins forever, and the rest of India benefited from it. Now, this fire has engulfed the rest of the country… So yes, the personal is political. It is not an intention. It is not a choice.

When I was growing up, we knew about [authorities] who used to come at midnight, knock on doors, and take people away, because somebody told them that they’re supporters of the insurgency, or involved in anti-government activities. They were dressed in army uniforms, so you didn’t know who they were; there were no name tags. When these people were picked up, they never came back home. And if you’re lucky you’ll get a mutilated corpse, tortured heavily. This happened all throughout my childhood in the early 90s. Nobody told our stories then. The Indian state has been practicing brutalities in the margins forever, and the rest of India benefited from it. Now, this fire has engulfed the rest of the country.

So yes, the personal is political. It is not an intention. It is not a choice. The personal won’t be political ever if the state is working, if the education system is working, the health system is working, the court system is working. Then, people will be able to live much more cocooned lives, and they won’t need to worry about the society, because things will be working.

When I wrote my first novel, some people in Assam said, “Oh you wrote about this violent space… What will people think about us? Our violent history? Please write about nice things, also.” As if it was my intention to write about bad things. I didn’t want to write about bad things. I want people who read my novels to laugh a lot. I was having so much fun, it was so pleasurable writing this. But bad things were happening—how do you separate them? It’s not possible.

TC: How has the writing process been like for you during the pandemic over the last few months? You’re also straddling issues between India and the US. In India, every ‘bad’ issue is looking worse with the pandemic, as if the sore has been made bigger. How has this year impacted your creative work?

Kashyap: I think I’m writing more, but I’m writing more non-fiction. One of the reasons for that is that non-fiction gives you the satisfaction of having finished it. You’re done—and you keep it aside. That satisfaction is really important.

Right now, I’m finding it difficult to stay with a sustained project for a long period of time. I recently wrote a very long essay on Indian literature for Catapult. It was very therapeutic to write that. I recently finished writing another essay on the tradition of novellas in American literature and Indian literature, and how novellas function differently in the global literary south, and how they’re seen as less valuable in American literature.

I’m writing personal essays that I’m sending out. The whole satisfaction of submitting—forget the acceptance, just finishing and sending something—is really giving me a lot of joy.

But I’m a fiction writer and I’m primarily a novelist. So, I’ve not been able to go back to a novel that I was working on. I work with multiple projects… But I have accepted the fact that, maybe at this point of time, I should be writing essays that finish in a week or so, send them out whenever I feel like, and then write another one.

TC: You have a poetry collection coming out next year, There is No Good Time for Bad News. Are these poems connected, or responding to a particular mood or theme?

Kashyap: Yes, the collection is responding to particular theme, which is basically the history of violence committed by the Indian state in one region. It starts from 1947, from Jawaharlal Nehru’s visit to a small village. And then goes on to talk about some key moments. They’re all dramatic monologues. Most of these are poems told from the perspective from different characters who are basically victims or survivors. We don’t usually hear about the survivors of state violence in Assam—we only hear the statistics.

It’s a series of poems from the time period of 1947 to 2012. I’m telling stories of the survivors and victims who faced violence or state brutality of some kind.

Maybe I want to ask: What does it really mean to live under violence? How does one negotiate violence? How does one live under an authoritarian state? These are broader questions that I’m asking throughout this collection.

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar, whose fiction, translation, and poetry have appeared in Gargoyle, The Literary Review, F(r)iction, and more. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, FirstPost, and more. Karan is currently working on his first novel. Twitter: @karanmadhok1