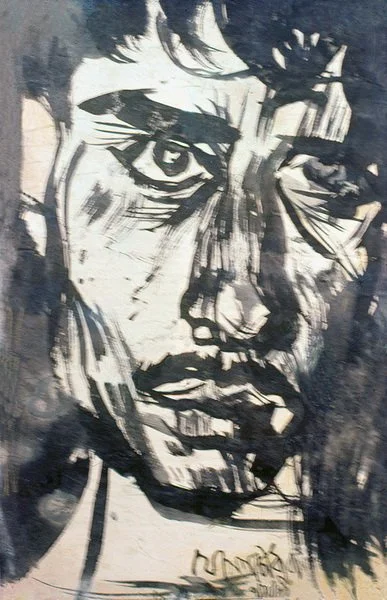

The Dark Webs of Jogen Chowdhury

Distortions and intimacy, revulsions and beauty: Celebrating the art of one of India’s great masters—Jogen Chowdhury—whose work continues to provide new insights to our world.

Jogen Chowdhury’s works have always reflected his personal agony. The artist’s post-Partition days in then-Calcutta (he was born in Faridpur in 1939, present-day Bangladesh), weigh heavily on his canvas. “My paintings are motivated by social and political injustices and reflect the situations around me,” says the modern master, who turns 83 on February 15, and divides his time between Kolkata, Shantiniketan and Delhi. “Dark has always been a part of my psyche.”

Political unrest, immigrants, refugees and more find space on Chowdhury’s canvas, in the form of distorted images merging with revulsion, and intimate figures streaked with disillusionment.

Spanning over six decades, Chowdhury’s works explore the enchantment of the everyday. Wearing his childlike curiosity on his sleeve, his canvas overflows with introspective self-portraits and satirical renderings of Bengal’s middle class—something he observed as a nine-year-old refugee from Bangladesh in crowded and tormented Calcutta. It was a traumatic period for the young Chowdhury, something he never really fully recovered from. His dark canvas harks back to his days as an immigrant in a foreign land. At the same time, there are intimations of transcendence flowing through the canvas.

Be it the concupiscent or estranged couple, the tonsured monk, or the courtesan whose limbs have lost their tautness, the artist invites viewers into a dark room where he lifts the veil off his subjects, and allows the viewer to speculate on the inner lives.

The octogenarian’s imagination is still largely coloured by the memory of his small village in Bangladesh—the tress and temples that sometimes crop in his works. Drawn to art at an early age, a young Chowdhury would keenly observe kumbhars, moulding the idols during the annual Durga Puja festivities at his zamindari household in Bangladesh. Later, the gifted child would use the leftover natural colours to make his own paintings. That was his introduction to the world of art.

Chowdhury’s disturbing yet riveting images are a powerful comment on the recent history of our country, peopled with isolation, upheaval and abandonment. Curator and art critic Ranjit Hoskote has said of Chowdury’s oeuvre, “His works interplay between the opposites: ripeness and decay; vitality and mortality.” And, why not? Chowdhury was witness to some of the most turbulent periods faced by the nation.

His works—save a short period during his stay in Paris—are often conflicted. In fact, they also speak of the pandemic that continues to rage across the world. In his own words, he likes “to leave a part of my compositions incomplete”.

Maybe it was the French Impressionist artist Edgar Degas and closer home, powerhouse Bengali talent Rabindranath Tagore, who encouraged Chowdhury’s “incomplete picture”, which he believes holds “the composition in place”. The artist has often spoken about how deeply these two greats from two opposite worlds influenced his canvas.

Unlike a lot of his peers, Chowdhury—an alumnus of the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata, from where he graduated in 1960—is not much interested in the medium of oil (though he has dabbled in it at times). It is the watercolour, charcoal, ink, pencil and lithograph that draws him. A multidisciplinary artist, one medium at one moment is not his style. A master of line drawing, his charcoal and pencil works render the realness of the people around him.

Chowdhury’s admiration for the lithograph stemmed from the time he spent with English painter and printmaker Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17 in Paris, while studying at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1965. After finishing his studies, he lived for five months in Lond that opened up his worldview on art and its possibilities. They bring out the torment and tension with each stroke. Chowdhury believes in rendering the everyday object artistic. Be it the concupiscent or estranged couple, the tonsured monk, or the courtesan whose limbs have lost their tautness, the artist invites viewers into a dark room where he lifts the veil off his subjects, and allows the viewer to speculate on the inner lives.

After his art studies, Chowdhury moved to Chennai in 1968 to work as a textile designer for the Madras Handloom Board. His stay till 1972 was unproductive as an artist. Chowdhury, instead, chose to write about Bengal and art. He finally quit the job in 1972, to take up the position of curatorship of the Art Gallery of the Rashtrapati Bhavan in Delhi. His stay in Delhi also saw him get together with his peers to establish Gallery 26 and Artists’ Forum in 1975. In 1987, he was back in Bengal as art professor at the Kala Bhavan in Shantiniketan.

Chowdhury’s canvas is that of the people—intimate, distorted, complex, deliberate—in relation to their environment and the world. It’s the drama of life as he observes around him. The vividly painted images are often agonising to look at. Chowdhury doesn’t care. He knows his images may be disturbing, but they are riveting nonetheless. The sear into the very imagination of the viewer. The man-woman relationship is something he is most fascinated with. Inspired also to a great extent by the Spanish great Pablo Picasso, Chowdhury’s figures are as intense and sensitive. The brutal images reveal weariness and pathos. Starting with abstract art in his early days, it took him time to find his own unique vocabulary sensuality and pain.

Acknowledged as one of the living greats in India, Chowdhury understands and respects the fickleness of the art world and the art connoisseur. “At my first solo at the Academy of Fine Arts, Kolkata (in 1963), I managed to sell only one work for ₹125. Much later there was a show at Bombay where all the exhibited 16 works were sold, followed by another show where I could not sell even one. I believe, my work if it is honest, will live, if not, it will disappear,” he says.

It is this search for ‘honest’ work that pressed Chowdhury to buy art by young unknown artists. An act of encouragement and validation no doubt, but the artist had more in mind. In 2019, he put all the art he had collected together and set up the Jogen Chowdhury Centre for Arts in Kolkata. In his own words, he wants “to generate more interest in visual art and cultural activities”. The Centre also has space for art residencies.

His art has been famously described by another Indian great—Bhupen Khakhar—as “vulnerable”. Vulnerable they may be, but they make one pause and reflect. The despair makes you question our very existence. The twisted figures with exaggerated pain writ on their face and mangled limbs, make one look at the world around you with a new insight. A dark insight perhaps, but one that is relevant to the times we live in.

***

Medha Dutta Yadav is a Delhi-based journalist and literary critic. She writes on art and culture. You can find her on Twitter: @primidutt on Instagram: @primidutt.