Gopi Gajwani, a Modernist product of Partition

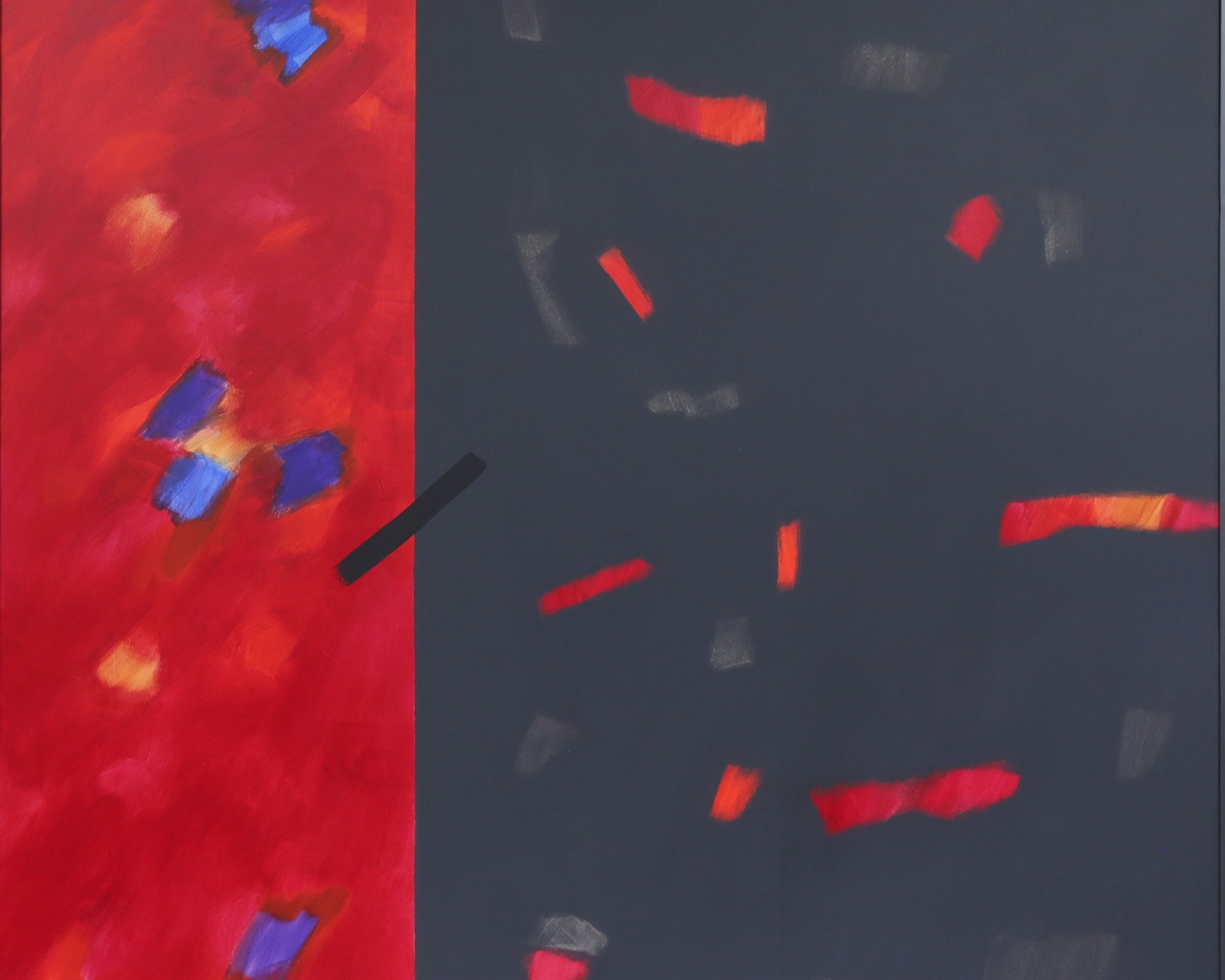

Untitled by Gopi Gajwani - Arcylic on Canvas, 58 x 58 inches, 2022

In the work of Indian modernist master Gopi Gajwani, the art features a strong sense of swirling and distancing, one that emerges as a glimpse of an image that is at once illusive and difficult to escape.

A glance at the artist Gopi Gajwani's canvases and paperwork at his recent solo exhibition, “Into the Gathering Night”, is a revisit to the work of modernists around the world. The show, held at the Shridharani Gallery’s Triveni Kala Sangam (New Delhi) and organised by Exhibit 320, featured the curatorial intervention of poet and curator Ranjit Hoskote, along with the assistance of the former gallerist and exhibition designer Prima Kurien. Gajwani’s abstractions here are a display of his deepest engagement with medium and moment. Gajwani himself reveals that much of his inspiration comes from the work of the American master Mark Rothko, adding that his school of art strains to show the deepest emotive engagement with one’s surroundings and state-of-being.

It is important to remember that Rothko’s Yellow and Blue (1954) and Orange and Yellow (1956) oil paintings influenced several artists of the later years of the modernist abstract expressionist traditions which, eventually, added to the oeuvre of the colour field paintings that can be traced into Indian art as well. Although Rothko’s oil paintings are often ascribed to the Washington colour school, one that is more focused on soak-staining to remove the brush strokes, it did give way, however, to a much more elaborate school of layering paint on paint, which was evident in Rothko’s artwork as well.

Untitled - Gopi Gajwani - Acrylic on Canvas, 18 x 18 inches, 2022

Gajwani’s canvases are layered with paint on top of paint. Oil on canvas is his favourite medium. His solo exhibit includes several acrylic, charcoal, watercolour, and Chinese-ink on paper and canvas paintings, too, and he doesn’t shy away from exposing his strokes and confident lines from public viewing. His artworks are stark displays of his skills as an artist, one who is clearly fond of his medium and the tools in his arsenal.

Interestingly, many of my conversations with Gajwani regarding his work revolved around how he allows his medium to dictate him around the flat-surfaces. He describes his technique as a means to engage with his medium—and not the other way round. Thus, if there’s a line running through the centre of a charcoal-on-paper piece, then the charcoal’s engagement with the paper demands this abrupt presence, and the artist’s engagement with his medium is to be able to demonstrate this charcoal line that divides the paper in two halves, or becomes one whole composition of several miniscule details. This is where Gajwani finds it difficult to elucidate and, thereby, invites his viewers to engage with his medium and display.

“Into The Gathering Night” is quite a step forward to coining important visual relevance of bold bright strokes with some chirpy notes. Blues, red, under-toned pinks, and neon yellows or greens peep out on certain bright navy blue, green, or black canvases.

Gajwani says that the works at the exhibit were created during the Lockdown, when his son was admitted in the hospital for COVID treatment, and he had the infectious spell twice, being treated mostly at home.

None of Gajwani's works carry any heading or title, except the year of their creation, a choice which adds to the ambiguity of the abstractionism that he explores. According to Gajwani, his colours are not mere reflections of his mood or his state-of-being, but his desire to show the most innate imageries of his humour and his candour. Given his past life experiences of drawing cartoons for publication and film-making, I wonder if Gajwani found painting to be a means to remove specific meanings, and instead lay emphasis towards abstractions. This is the most valuable aspect of the arts that he explores—especially in the work of the modernists.

Gajwani’s practice is also a masterful continuation of the modernists abstractionists school that emerged in South Asia post the 1950s, one that also features a more nuanced intervention of modernisation or technological advancements where compositions and colour theories provide relevance for Indian artists as well. Artist Vasudeo S. Gaitonde’s abstractions also revolutionised the visual schools with a sense of freedom from previous traditional schools of arts and radicalised visual cultures in India, which can be traced in much of Gajwani’s works, including his films. Gajwani himself professes that he has found inspiration in the works of the artists Prabhakar Kolte and Vivan Sundaram.

Untitled - Gopi Gajwani - Acrylic on Canvas, 58 x 58 inches, 2022

Gajwani’s practice was initially mentored by Sailoz Mookherjea, one of the important nine artists recognised as ‘national treasures’. He graduated from Delhi College of Arts (formerly known as Delhi Polytechnic) and pursued his artistic dreams. Over the years, Gajwani has become an important reference for artists willing to explore the meaninglessness of the world, while leaning on art to expose their deepest sentiments to the public.

“Into The Gathering Night” is quite a step forward to coining important visual relevance of bold bright strokes with some chirpy notes. Blues, red, under-toned pinks, and neon yellows or greens peep out on certain bright navy blue, green, or black canvases. Interestingly, in all of Gajwani’s works, there is a strong sense of swirling and distancing emerging as a glimpse at some illusive image, one that is difficult to escape.

Kurien’s presence marks the very beginning of the show, as she buids a butterscotch yellow wall to hold a charcoal on paper artwork from Gajwani’s 2021 practice, alongside Hoskote’s lyrical introduction to the display. Interestingly, the curatorial note mostly explains through references to emotive responses to classical music. This adds an unheard musical spin to the entire showcase of Gajwani’s art.

The rest of his works at the exhibition were lined up on the sides of the hall. Some of these works came in three different canvas sizes, almost creating a synchronic gesture for people to engage with the different forms. A wall at the back of the hall emerged as an extension where his watercolour-charcoal works are staged in a row. These works carry the image of small brick-like structures, which were placed between lines. Some have a whirlpool-like form staged between these lines along with small blocks of charcoal sketching. In all these sketches, a block of watercolour paint in brush strokes forms a background in the most organised fashion, almost giving it the look of soak-stains. Another wall that formed the end of the hall was also staged with a mix of big canvases and paperwork.

An audio-visual tablet-based display was hung on the wall at the side-corner of the entrance gate, along with other charcoal on paperwork and small acrylic on canvas works lined along the wall. The organization of this display definitely helped to enhance the viewing experience of Gajwani’s artwork.

Untitled - Gopi Gajwani - Charcoal on Paper, 21 x 19 inches, 2022

Another very interesting aspect of Gajwani remains hidden in his works: his Sindhi origin and his experience with Partition. Gajwani explained these aspects to Hoskote as ‘wounds’ that have become colourless over time. Born in 1938, the artist was a mere child at the time of Independence. He reminds us that during the period of Partition, we as a people had been promised freedom and walked into ‘a bright future’, but, now, he doesn’t yet know if that promised freedom has been achieved.

Speaking in Sindhi, hearing Hindi songs occasionally on gramophone records during his childhood, Gajwani spoke about coining a new lingua for his language through his brush and paint. These are the strokes that came from a child of Partition.

***

Satarupa Bhattacharya is an independent cultural practitioner, associated with academic journals on visual and cultural studies. She is currently working on academic publications and a novella. You can find her on Instagram: @sattybatty.