With ‘Episteme’, Ten Indian Artists Translate the Language of Now

Untitled - Pinaki R Mohanty

Contemporary retrospection—an attempt to comprehend not the distant past but the present day—was the central theme of Episteme, an exhibition in New Delhi featuring ten emerging Indian artists.

In the first installation, two rows of flamingos—hundreds of small ceramic figurines—stand huddled close to each other, crowding over the flat stretch of the slab, as they would in their natural habitat beside a body of water, sharing a moment of familiar stability.

Flamingos populate the second installation, too, right next to the first. But now, their arrangement could hardly be more different. Gone is the stability of their neat, standing row; these flamingos—this time, carved out of wood—now stand at a disparate distance from each other, each on a lonely, small piece of rock, separated from their flock, displaced by some form of disaster.

Disaster and displacements have been a central motif in the work of sculptor and painter Pinaki Ranjan Mohanty for years. The artist, who grew up in Odisha’s Gopalpur, has often focused his attention towards Chilika, the biggest lake in the country. The lake, and the wildlife that it attracts like the migratory flamingos, have befallen victim to poaching and ecological decay, to over-industrialisation, pesticides, and cyclones. Mohanty’s two untitled sculptures are a silent cry for attention for these ecological changes, a retrospection of an ongoing catastrophe. The flamingos and the rocks in the second installation are made of found materials from the lake itself—adding a further layer of displacement.

Episteme at the Art Centrix Space, New Delhi.

This form of contemporary retrospection—an attempt to comprehend not the distant past but the present day—was the central theme of Episteme, an art exhibition featuring 33 works by ten emerging Indian artists. Curated by Monica Jain, Episteme was shown by New Delhi’s Art Centrix Space from November 11 to December 11, 2021. It was the gallery’s first physical exhibition after the long year and a half of the COVID-induced shutdowns; the newly launched space hopes to be a hub for South-Asian contemporary art, to nurture young and mid-career artists, and to host programmes of artistic exchanges, exhibitions and curatorial interventions.

The last few years of the pandemic has added an urgent, almost desperate need to make sense of the world around us, to perhaps attempt the impossible of understanding the present day without the wisdom gleaned from the passage of passing time. In an interview with The Chakkar, Jain used the example of Mohanty’s installation to comment on how the Episteme series hopes to forge the connection again between artist and observer, to help translate emotion through the language of art.

How do we adequately understand our present—the hyper-contemporary—without the luxury of time and reflection? It is a tricky endeavour for anyone—historians, writers, scientists, leaders, and lawmakers—but artists can perhaps offer as close a comprehension as anyone.

“Look at the impact of nature on humanity today,” said Jain. “Over the years, artists and art galleries have been talking about environmental impact. I think this is the first time that humanity really got effected.”

Episteme teemed with this sort of commentary, reflections of humanity’s relationships with geographical areas. The exhibition features artists including Mohanty, Kundan Mondal, Amjum Rizve, Manish Sharma, Mainaz Bano, Tapas Biswas, Soham Raha, Sangam Vankhade, Pratik Raut, and Vijaya Chauhan, each exploring socio-political history through a contemporary lens via the senses. The layered narratives of their work questioned topics including ecological problems, man-made capitalist problems, colonialism, power relations, indigenous cultural practices, and new forms of communication.

Returning to a physical exhibition after the long shutdown, Jain wanted the new Art Centrix Space to provide a type of sensory experience only made possible when witnessing art in person. One example of this is Vijaya Chauhan’s “Unread Sentences” series, where the artist highlights the imperfections of senses through stoneware on wood installations that communicate in deeper and deeper layers: first to the visual observer, and then, in its tactile quality in Braille, to those who explore the emotions through a sense of touch.

“It helps to connect, when one has the sense of wanting to reach out and touch a work of art,” said Jain. “You can see a lot of sculptures and installations here. The paintings have a very tactile quality, even though they are encased in glass. It tends to activate the senses.”

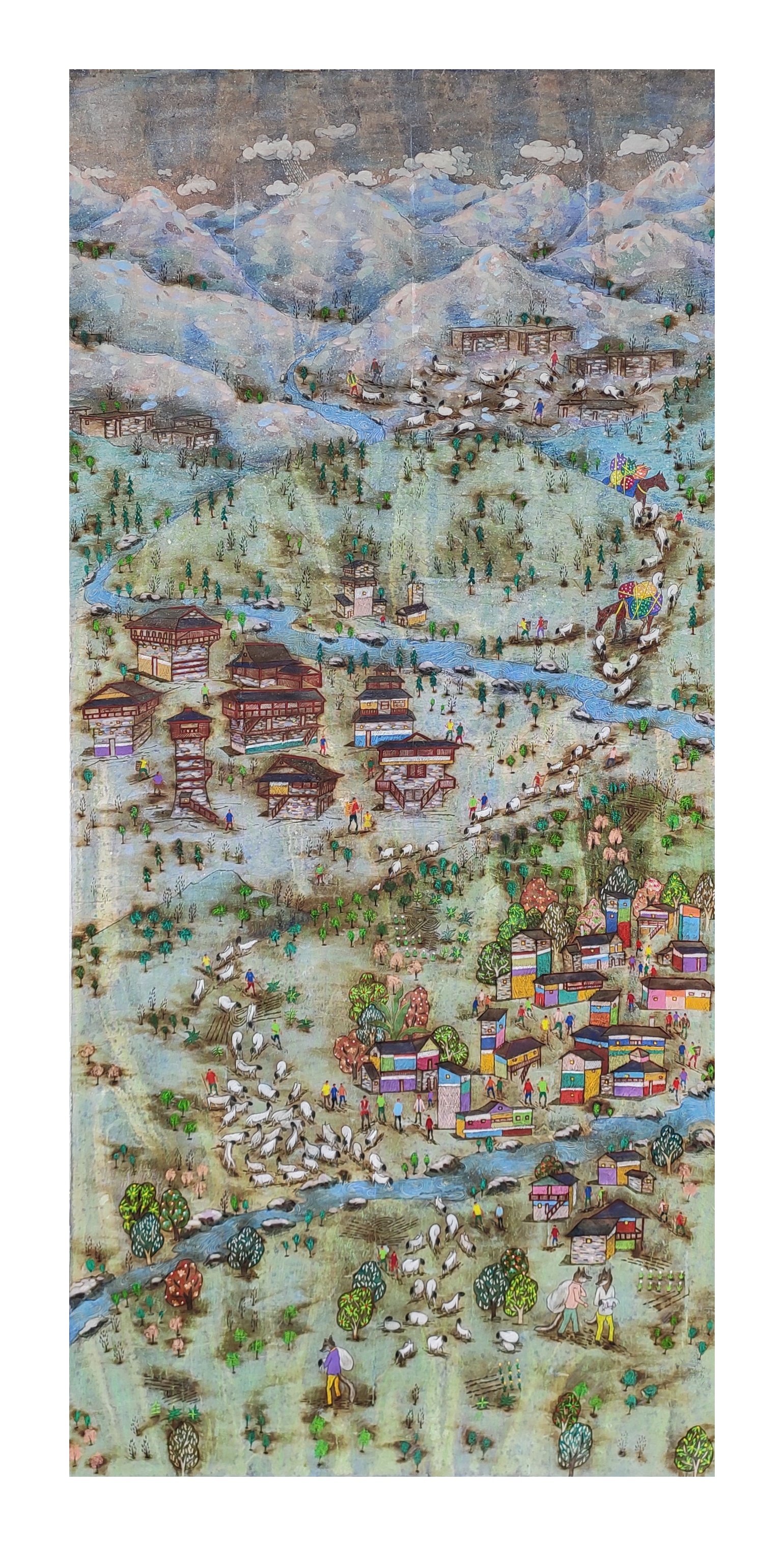

Seasons of Life - Pratik Raut

There were examples of this tactile energy abound, from Sangam Vankhade’s marble sculptures, Pratik Raut’s mixed media paintings that gave the remarkable illusion of both depth and expanse, or Amjum Rizve’s dreamscapes, which, inspired by Islamic symbolism, tell stories with colour, jewellery, and beads popping up and off the canvas.

“Rizve used lots of different kinds of beads, embroidery, jewellery… It was a way for him to imagine a different type of composition,” said Jain. “He’s inspired by Islamic motifs and embroidery that you see in Middle East and India. It builds a kind of textural quality. Yet, the whole composition flows together. It is sensory, yes. But it’s not only sensory: You can have a lot of such materials being used. But they have to be translated into a form of art… See, we’re not looking at something superficial. The underlying purpose of art is to reach out to a certain part of us which we are not able to reach out with words or through music… But it should touch us. Something that is beyond grasp—and yet, we can have multiple ideas of what it really is.”

Rizve’s work also leaves the observer with a real sense of yearning, as if something is missing, a jigsaw puzzle left incomplete, a perforation. “One of the interesting paradoxes of a sensory experience is that, the more you touch, the more you yearn for it,” said Jain. “It remains elusive.”

For Jain, it was of tantamount importance that the artists picked for the Episteme exhibition had a longstanding relationship with the gallery. She had been working with most of the artists for a half-dozen years, and wanted the space in New Delhi to reflect not just the art, but the journey towards the final pieces of work. “We wanted to be part of their lives,” said Jain. “The pandemic taught you to be there for each other in good times or bad.”

One of these artists is Manish Sharma, whom Jain showed in the 2019 India Art Fair and the Arikamendu exhibition in 2018. Currently a resident of Jaipur, Rajasthan, Sharma’s work has toyed with the complexities between art and politics, of nostalgia and cultural criticism. The visual element of his sculptures has often featured the colour gold—evoking that sense of ancient wealth and nostalgia.

Sharma’s headlining display at Episteme was dripping with gold, too: small, winged sculptures of 24ct gold on fiberglass. The piece, entitled “Flying Senses”, also sees Sharma mould his nostalgic tendencies with a bold, new escape into modernism. The ‘flight’ was the artist’s interpretation of human restlessness during the Lockdown, the yearning for sight, smell, and sound and more beyond the four walls of isolation. Jain suggested that Sharma wanted to evoke this idea of being locked up, and then, a sense of freedom, too. To get out of a tough emotional, psychological space, to find freedom through this work, to let the work soar.

“Earlier,” said Jain, “[Sharma]’s works were about museums and the idea of preserving the past. Here, I think it has been about finding release from the present, and for the future.”

This circles back Episteme to its trickiest ambition as a collection of art: How do we adequately understand our present—the hyper-contemporary—without the luxury of time and reflection? It is a tricky endeavour for anyone—historians, writers, scientists, leaders, and lawmakers—but artists can perhaps offer as close a comprehension as anyone.

Flying Senses - Manish Sharma

“I believe that the artists have an understanding, its imperceptible and it comes out through their work,” said Jain. “And somehow, when they work—wherever they are from—we can have a collective consciousness, which comes out, even through diversity. So, this show is about showing that paradox of what they are all thinking.”

“I think the biggest challenge of curating is putting together something very diverse, and for it to work together. It is the idea of making sense of a time, even while we’re living, breathing, creating through it.”

And it is through art, perhaps, that we’re best able to translate this new language for the present, whether it is through the emotional yearning for sensory escape, for the search of the missing other, for marble stepwells into mysterious new journeys, or for a flamboyance of flamingos, separated into their individual isolations.

“Art like that has come out of observation,” said Jain. “Its quality is something critical, an abstractness that we may see in film, music, something intangible that we can’t quite grasp. It’s what actually differentiates something that is more functional, or maybe more design-oriented, from a work of art.”

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar, whose fiction, translation, and poetry have appeared in Gargoyle, The Literary Review, The Bombay Review, The Lantern Review, F(r)iction, and more. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, FirstPost, and more. His debut novel is forthcoming on the Aleph Book Company. You can find him on Twitter: @karanmadhok1 and Instagram: @karanmadhok.