A telling of our times: The art of Ashok Bhowmick

Image courtesy: Gallerie Splash

In his latest exhibition, Ashok Bhowmick creates a dialogue between the artist and his viewers without any façade, inviting people to engage with his visual play of geometric shapes and patterns, colours, lights, shadings, and textures that inadvertently take shape.

Ashok Bhowmick wants to remind us to look back in time, to consider the ripple-effect created by the European Renaissance arts on the rest of the world. His most recent exhibit—Made in the Shade, organised by Gallirie Splash in collaboration with Dhoomimal Gallery at New Delhi—further urges its audience to look deeply at postmodernism in Indian art, reiterating the Australian theorist Niall Lucy’s definition of the postmodern as an ongoing practice of completing the incompleteness of the Romantics—or, in this case, the Renaissance. Bhowmick particularly applies the practice of combining European techniques to the coining of a visual language, one that is particularly evocative of an Indian reality, especially performed through symbolic references of the turns and turmoils that have led to modern day India.

The distinctive technique of cross-hatching and the cubist figure is Bhowmick’s primary engagement in his art practice. It comes alive at the gallery Connaught Place, a place that is also considered to be a reimagined version of the Royal Crescent at Bath, England. We are almost driven to look at the art of recreation, or revisiting time and space, in order to look at the immediate visual currency in Bhowmick’s works. Here is the best instance of witnessing the very base of ‘nostalgia’, recreated and perfectly instilled while it dabbles with the idioms of structure and conclusion. Bhowmick’s work tries to break glass ceilings to envision a past that was still in the process of turning into a world and space like ‘now’. Made in the Shade may just be a beginning to this engagement in public.

We are almost driven to look at the art of recreation, or revisiting time and space, in order to look at the immediate visual currency in Bhowmick’s works. Here is the best instance of witnessing the very base of ‘nostalgia’, recreated and perfectly instilled while it dabbles with the idioms of structure and conclusion.

Curated by Monika Ajay Kaul, Made in the Shade showcases Bhowmick’s work from the 1980s to 2022, and also includes a number of fascinating black and white creations.

Most of his works claim a deeper exchange with the world that he is surrounded by; thereby, he tries to break this imagery into several important fragments as seen in his canvases, paperboards, and other mediums. Every image is further fragmented in his technique of cross-hatching, where a minute space adds to the larger frame of the image that we are eventually exposed to. This is part of his deconstructive act in his creation, whereby he is able to interact with each bit of the flat-surface that he uses to narrate his story. The act also states his political voice engaging with the very model of the ‘real estate’ value often attached to the artist. This is to say that not only does Bhowmick recognize the functional role of the artist in society and politics, but also the role of the artist in creating an economic value system.

Interestingly, when Bhowmick talks about his approach, he reminds his viewers that his techniques are a means to communicate with them in the most direct manner possible. The idea is to create a dialogue between the artist and his viewers without any hindrance or façade, and to invite people from all walks of life to engage with his visual play of geometric shapes and patterns, colours, lights, shadings, and textures that are inadvertently taking shape.

The exhibit exposes viewers to Bhowmick’s variety in form, and the further microscopic examination of these forms and figures. This is evident in his canvas named “Lockdown 2”, which is an acrylic, pen, and ink crosshatch work, where we see a bird perched outside a cage, while looking backwards at it. The image is strongly drawn with the intent of an aftermath that is particularly important in the act of turning and looking behind. The message here is poignant, pushing for a dialogue on memories and its symbolic references. Here, the artist engages with the simplest message coded in the use of the red colour that is used on the bird and around the separated space where the cage is staged.

The bird itself generates a sense of mirth, and carries a fuzzy missive in some of his other works present at the show. “Amina and the bird”, “Jester 1”, and “The warrior” are all acrylic, pen, and ink crosshatch on canvases that generate warm engagements with qualities and emotions of his characters and nature.

Another similar instance of symbolic engagement is seen in his work “The bull 4”, which is an acrylic, pen, and ink crosshatch on canvas, where the face of the bull occupies most of the flat-surface, and the different shades of red begin to chalk out the form from the space it is staged on. In the most regular dictums, the bull marks masculine energy, might, power, and labour in India while it also stands as ferocity, stubbornness, tyranny, and brutality. Given the expression of ferocity in the bull’s eyes, the imagery generates a special meaning of resistance and steadfastness.

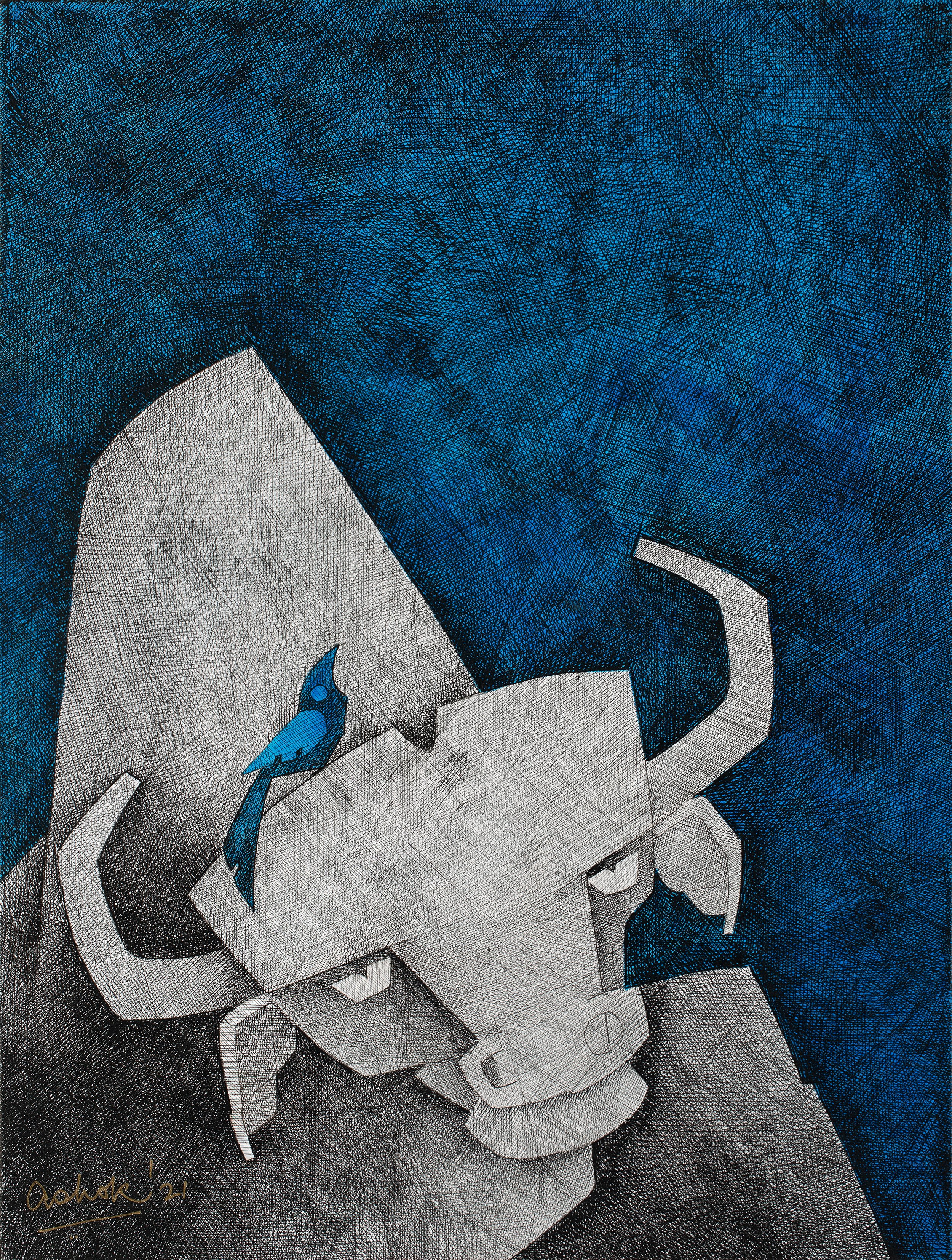

Similarly, the bull has different humorous meanings in his acrylic, pen, and ink crosshatch on canvas in “Bull and the bird 2”, where we see a bird sitting on the bull's horn. Here, the bull's eyes convey gentility towards the bird while the bird looks upwards, almost avoiding eye-contact with the bull.

Image courtesy: Gallerie Splash

Bhowmick’s practice also recreates the warli art form as evident in his acrylic, pen, and ink crosshatch on canvas in “Warli in me”, where he works with the special stick-like geometric shapes on a blue-green background. While invoking the traditional Maharashtrian art practice, this particular painting engages with a more modern flavour through the shaded colours and his expert techniques. This goes on to further elucidate Bhowmick’s ability to masterfully bring together several art forms and practices in one place to recreate a visual language that is particularly his own.

The exhibit also included several elaborate pen and ink crosshatch on ivory board works. One such instance is seen in “The red light”, where three masculine heads are facing upwards towards a feminine head drawn in between palanquin-window-like structures. Similarly, “Roots” has a feminine form placed against fragmented roots and branches of a tree.

Interestingly, Bhowmick's female form is rooted in the historic curves and softened expression of the face, particularly attributed to the presentation of the feminine. The artist also alludes to landscapes through the female body bringing forward the discourse on fertility, nature, and creativity. Hairstyles are important markers of the female presence. The male form has a more square-like shape and possesses valourous details, such as the harsh demarcation of the skeletal structure of the face. These little details vary from one work to another and they mostly generate a visual dialogue between the emotive responses of the character and the circumstances placed in Bhowmick’s narration.

All in all, Bhowmick’s art is an intricate process of engaging with details and influential moments that he has encountered in his life. He is able to entertain his viewers, but also helps to conjure up a deep empathy for the world we cohabit. Bhowmick is an artist actively involved in recreating images that are particularly important in telling of our times.

***

Satarupa Bhattacharya is an independent cultural practitioner, associated with academic journals on visual and cultural studies. She is currently working on academic publications and a novella. You can find her on Instagram: @sattybatty.