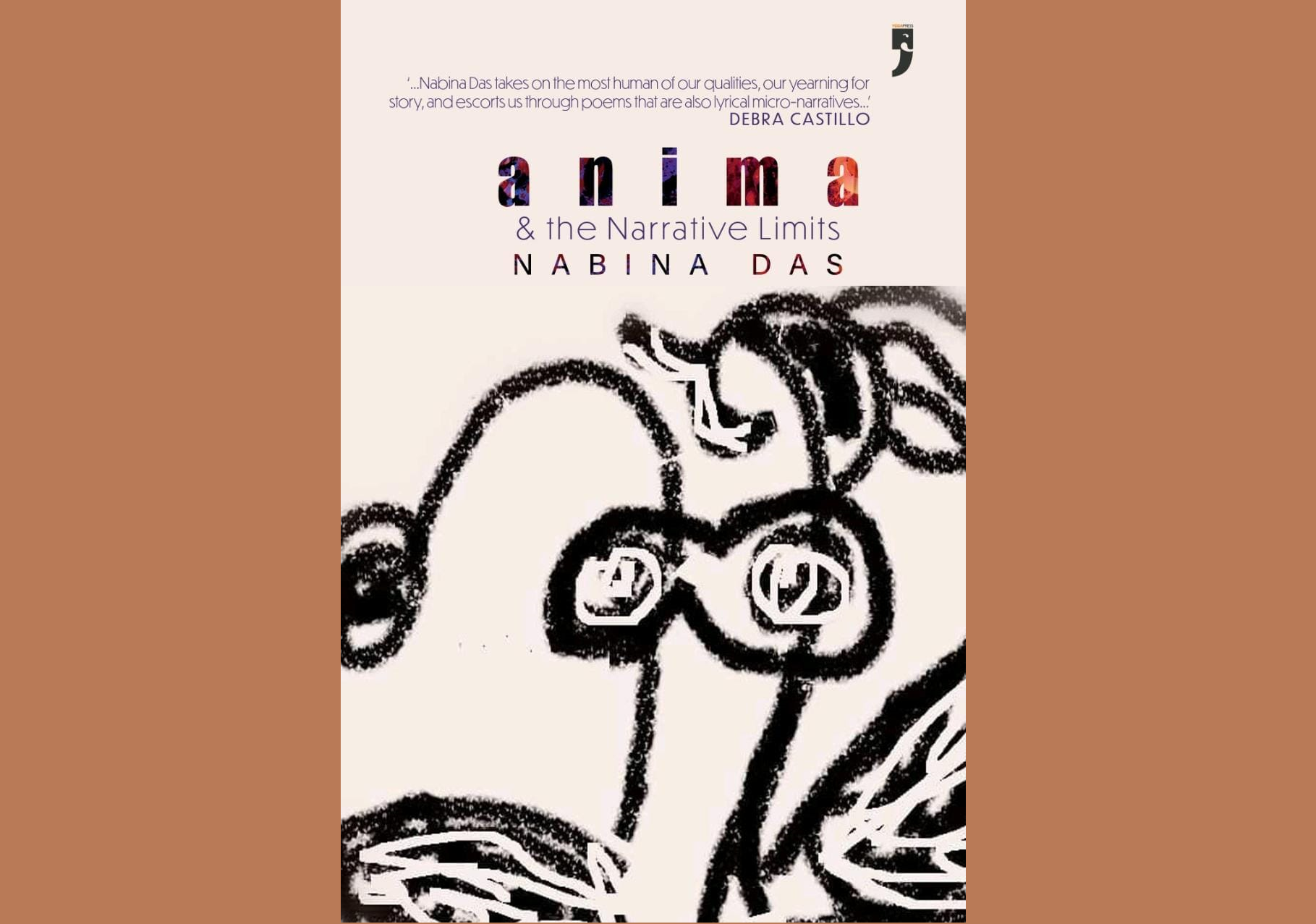

A Poetic Clarion Call to the Feminine Presence—Nabina Das’ ‘Anima’

Photo credit: Yoda Press

In a series of poignant poems from Anima: & the Narrative Limits, Nabina Das personifies the feminine energy of ‘Anima’—as she tells stories, observes the social fabric of humanity, poses questions to history, and explains the world through her perspective.

In Nabina Das’ verses, there is always a larger, more complex narrative hiding behind the surface, scratching and clawing to make its way out—until finally, it leaves an imprint of itself, until the poem before you is not a poem alone, but a quick flashbulb of a story that is capable of illuminating the whole room.

Das is the author of three previous poetry collections—Sanskarnama, Into the Migrant City, and Blue Vessel—a novel titled Footprints in the Bajra, and a short fiction volume titled The House of Twining Roses: Stories of the Mapped and the Unmapped. In her latest work, Anima: & the Narrative Limits (Yoda Press, 2022), the poet gets as playful as ever with her verses: Her words travel and meander; but even in the darkest alley, they hold on to your hands, guiding you through the twists and turns until you find the meaning you were always intended to find.

The poem “Anima Takes a Stroll in the Park”, for instance, is one such example of this meandering, guiding light: While describing a park, the narrative voice of Anima—almost accidently, just happens to stumble upon truths of colonialism, religion, deforestation, neem trees... and the thread connecting many of these poems in the early part of the collection: the feminine energy in all gender roles.

For that is the core of this latest collection. The concept of ‘anima’—in Western, Jungian psychology—is described as the feminine principal of all things, and one that is especially present in men, too. Das explains her interpretation further in the introduction to the collection,

My readers would have guessed it by now that these poems are starkly feminist and call upon men and women who see themselves not simply as radicals—to allude to the ignominy some people heap on the term—but also as those who will sing and celebrate speaking up. Anima, this way, is a clarion call to the feminine presence in all of our lives, nature’s healing, and bonding between the stakeholders desiring peace and regeneration.

This feminist voice takes personified form as Anima, and Das whisks us along into narrative and abstract adventures with ‘her’ through the first part of this collection. In a series of poignant prose poems, we encounter Anima telling stories, observing the social fabric of humanity, posing questions to history, and explaining the world through her perspective.

Anima’s identity—which is sometimes overlaid over the masculine—is established early in this loose narrative with the poem “Anima Stands in the Bazaar”. Das writes: “You can’t tell whether it is a man or a woman. She-he has a face made of moon wrinkles and wears a long piece of white dhoti spun from Hatigorukhuwa. No, that place is really real.” This poem welcomes the readers into a bazaar of stories. From here on, each poem that follows is a tiny ‘packet’ handed out, with bits of wisdom. “I, Anima, will tell you next what the meatseller is sharpening his cleaver for”, Das finishes, setting us up for the next tale.

One of those little ‘packets’ of wisdom is “Anima Asks of History a Few Questions”, where Anima’s line of queries draws the narrative forward, offering deeper answers in subtext hidden between the loud silences on the page.

Do you know stale rice can make you swoon? Do you walk the town roads looking for old facades? Do you ever watch your face in a mirror?... Do you peep in to see how dark is the black market? Do you try to catch a rainbow after the headline-making floods? Do you lend a hand to those who can never rise?... Did someone ever call you skin-tanner, shoe-maker, shit-hauler, fishscaler, carcass-burner and dead-soother?

Another example of a poem that meanders into something deeper is “Anima of the Old Dancer City”, where the imagery and emotion become more and more evocative with each uttered breath. It’s almost an ode to Calvino, evolved now with the sprinkling of South Asianness largely lacking in Invisible Cities. Something new is born, and it’s a birth that keeps giving birth.

Many of the poems, like the aforementioned “Anima Asks of History a Few Questions,” end with a promise of continuation. “I, Anima, will return to you with another questionnaire.” Like Scheherazade, whose life depended on the hook for the next story, and the next one, Anima keeps the reader on their toes, engaged to turn the next page, with promises of more truths revealed, poem after poem. A cliff-hanger concludes “Anima Watches a Sure Death,” too, where Das writes, “I, Anima, will tell you next time, why some people die very many unsure deaths.”

Her words travel and meander; but even in the darkest alley, they hold on to your hands, guiding you through the twists and turns until you find the meaning you were always intended to find.

In “Anima Takes Back the Night”, Das flies from one vivid image to other, mixing the contemporary, the magical, the mythological, the abstract with the slap of a jarring sensory awakening:

My alley has been a gossip for many years, mouths dribbling of fears and lies. Did you know, they ask each other—a dragonfly-winged pori walks the night’s backbone when she sings instead of sleeping. A high-heeled deity shows you her henna palms painted in the body’s extract. A leather-jacketed back carries the moon and the stars that were thrown off in tied gunny sacks with women’s names.

By spotlighting ‘narrative limits’ in the title—as well as the middle section of the book—Das deliberately urges the reader’s attention towards the art of storytelling, and its unique function when expressed through verse. It’s something that we expect from ancient epics, but rarely in the guise of short-form verses that make for much of contemporary poetry. Many of Das’ poems—particularly in the ‘Anima’ section—unfold with the ambition of this larger narrative, even if it’s fed to the reader through small, bittersweet bites.

Parts II and III of Das’ collection shift away from the ‘Anima’ voice, but stay loosely tied to the collection’s themes in newer forms. There are a number of ghazals here, including “New Words in This Grammar”—a meditation on memory—“Healing amid Ruins”, and “Come Eat My Lotus-Heart”. “Flowers of Light” is a well-intentioned rumination on oppressive social fabrics of our nation, but takes a slightly-awkward, preachy tone, missing the vivid weight and introspection from the earlier section. The lovely musicality of these ghazals is undeniable, but the strict adherence to the form sacrifices the complexity of the content itself.

One of the standout poems in this section is “In Happiness, Tremble”, where Das, with gorgeous lyrical control, captures the heady feeling of risk that accompanies joy:

Nabina Das. Photo credit: Yoda Press

We think it is in happiness

that it trembles on leftover

soup bowls, rice plates, din

that we make. All the while

we suppose we’re living.

Her poetic voice here is confident and precise, efficient in the details as well as in the larger narrative that it weaves, poem after poem.

Das plucks her way through other poignant themes in the rest of her poems, like an ongoing correspondence in the foreground of violence and separation (“When my letter quoted: ‘Main tenu pher milaangi…’), the intersectional politics imposed upon different oppressed groups (“Speak to Us of Clothes”), and of women shaped for public consumption by the male gaze (“Perfection as Immunity”).

A highlight of the second part are the three linked poems, “The World in my Solitary Veins”, a journey where memory leads to trauma, but is sprinkled with beauty, too:

We were taught to find colors in

the sky. Blue from airy old scars

Spread over. As though my dreams.

Until I realized dreams bled nothing

Only reality did. The way my dad’s

Head bled when he had the stroke

And fell down on the wide terrace.

Das ends the collection with the third part, titled “A Few Things of Consideration”, named after a poem that comments on the barrage of distraction numbing us from true emotional reaction in life. Her words contort and twist in this section, phrases are reshaped, images metamorphize into new images. Sometimes, the narrator is “delivered and my / soul to a bandage-unwrapped hand”. Sometimes, this narrator skips past time and space, such as in “Lost Landscape”, where a leather-jacketed book leads her to childhood, to the classroom blackboard, to death. Das in this poem poses the pertinent question of language and life: “What dies when new words are born?”

Sometimes, this narrator skips past time and space, such as in “Lost Landscape”, where a leather-jacketed book leads her to childhood, to the classroom blackboard, to death. Das in this poem poses the pertinent question of language and life: “What dies when new words are born?”

While these latter parts of the collection provide many similar moments of charm and insight, it is back in the expressions of ‘Anima’ where the poet’s voice truly rises. Some poems, like “Anima of the River’s Arm”, sweep through like a grand narrative, a scene unfolding before our eyes, a character emerging, a plot taking shape. “Evening falls. The big bend of the river has everyone in its thrall like the first virginal blood. The sun has also shed its vermillion sap in the deep deepness of the water’s pull. The blueing of the faraway hillocks has my thighs shiver where your mouth left the half-moon marks.” Das, who blurs the lines between prose and poetry with easy grace, then swoops in with the breath-taking line, “Come be the goddess who jumped into the river and raised a fist before she swam away.”

The idea of goddess flows naturally to “Anima Writes a Goddess Story” in the very next poem. This is a story of Durga, or the many Durgas, named after the goddess, all of whom face the consequences of every woman in this country.

Sometimes, Anima is a goddess herself, and sometimes, she is a poet. She sees the world through caste barriers and gender barriers. She stops and starts again. Das finds this voice exploring themes of decay and reinvention in “Anima and the Ballad of Breath”: “We rise from our gone-bodies, we reinvent the joyless earth, atom by atom. We make every breath a promise that we will bring you down.”

Das further subverts the formlessness of this feminine energy when Amina herself seeks out some form of concrete footing for herself in “Anima Walks Borderless”—for a body, a state to call her own, a place, a physicality. She can only conclude to define herself as a wandering soul with the final words here, “I’m a jajabor”. Later, in “Anima of the River's Arm”, she adds that she is beyond abstract ideas of creation, too: “I, Anima, am of no mantras, no deities, no one source.”

By the penultimate poem in the first part, Anima’s word takes specific and vivid shapes (“Anima Rearranges a Nostalgia”). Images flash into existence and flash away again, dreamlike at first, and then build quickly into a heavy-weighted crescendo. There’s a sudden, delightful shift to Hindi, before Das writes, “No one will remember because nostalgia is a flower that dies at dawn.”

If one hasn’t caught on to Anima yet, it’s because Anima chooses to be uncatchable. From Das’ perspective, the personified Anima—as well as the psychological anima—is not one thing, and thus is every such thing. She’s playful and meditative, observant and fickle, formless like water, taking any form she wishes.

She urges the feminine lens of the world—and more specifically, upon the world of men. And there’s no escaping her.

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar. His debut novel A Beautiful Decay (Aleph Book Company) was published in October 2022. His creative work has appeared in Epiphany, Gargoyle, The Literary Review, The Bombay Review, The Lantern Review, and the anthology A Case of Indian Marvels. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, Fifty Two, FirstPost, and more. You can find him on Twitter: @karanmadhok1 and Instagram: @karanmadhok.