TVF’s continuing ‘Aspiration’ as the voice of India’s Youth

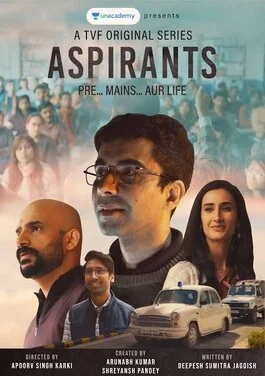

A still from TVF’s Aspirants (2021).

With coming-of-age series Aspirants, streaming platform The Viral Fever continue to tell stories close to the heart of the Indian youth, serving as an evolving meme of our times.

A friend of mine—let’s call him Ani—unexpectedly turned ill at ease last summer. However, contrary to the currents of the times, his restlessness wasn’t induced by the deprivation in isolatory ways of living. For him, isolation had instead served an alternate purpose altogether: of setting into motion a deeply contemplative course of events, a rethink of the choices he’d made as a student thus far. Days and weeks of soul-searching later, when he arrived at a decision, he messaged me, his words affirming the conviction in his conclusion: ‘Decided, I’d prepare for UPSC’ [Civil Services Examination]. In our subsequent conversations, I would come to know that he’d also decided to opt-out of the cycle of internships and placements, to prevent any possible comfort of cushion one could derive from a fallback option, leaving little room for insincerity and inattention.

The zeal to become a civil servant in a beleaguered administration of this country can come across as remarkably surprising at times, except it is also uniquely driven by the very force of a potential ‘change’ that can undo that malaise in the system—a change to be afflicted in the values and the character of the system itself. The trails here reek of ambition and desire, but more importantly and assuringly, they celebrate hope in the most chaste of forms possible.

The show opened to an overwhelming response, signaling that the chieftain of ‘relatability’ was intact with the house of TVF, a singular quality that the desi storytelling platform has come to inhabit ever since its origin.

Aspirants, a web series released by The Viral Fever (TVF) in April this year, can then be described as the embodiment of that steep slope of hope and courage demanded in a journey of any such aspirant in this country. The show, instantly beloved by viewers, opened to an overwhelming response, signaling that the chieftain of ‘relatability’ was intact with the house of TVF, a singular quality that the desi storytelling platform has come to inhabit ever since its origin.

TVF’s dawn in the digital media sphere coincided with the rising popularity of YouTube in the country. Right from its launch, TVF positioned itself as a novel attempt to fill the void between the soap operas airing on Indian television and the cinema of the globe, in an attempt to develop shows and content of and for the internet age of India. Indian television had very little to offer in this category back then (and even now), barring popular college rom-coms like Sadda Haq and Dil-Dosti-Dance on Channel V, or the overtly mercurial task-show Roadies on MTV. The internet had only begun on its expansionary note, with more and more in millennia turning to smartphones, curiously exploring its expansive world of education and entertainment. Rowdies, a satire on the temperamental attitudes on Roadies, soon became the first of a spree of spoofs and spin-offs from TVF’s stable. The motto was set straight: create content that borrows from the lives of their target audience. It helped that the writers and producers of the show hailed from the same age group as their target audience, and were essentially working towards satiating a hunger they had themselves felt.

When the final episode of Aspirants dropped on the May 10, a flurry of reactions emerged, most of them lauding TVF for making an authentic reel of their lives, and others gushing over acquiring the knowledge of what it takes to be a UPSC aspirant. The show was a stamp on TVF’s authority in the slice-of-life arena, telling precisely of the coming-of-age story of a production house started by a group of dilettantes.

Aspirants rallied with the oft used formula of a triad of friends (literally called ‘tripod’) and set out to trace their storylines from being an aspirant to their respective destinations. The characterisation, at least subtly reminiscent of the pioneer of the three-friends-trope Dil Chahta Hai, based the traits of the three friends in a similar vogue as the 2001 pathbreaker. A large share of the charm and resonance of show in fact drove itself from the distinctive qualities of the three friends: SK (Abhilash Thapliyal) as the level-headed peace broker, keen on preventing any knots in the thread that ran across the trio; Guri (Shivankit Singh Parihar) as the happy-go-lucky friend, perennially nonchalant and impulsive; and finally, Abhilaash (Naveen Kasturia) as the stern and serious partner, emoting only in appropriate amounts, not less, never more. Anatomically, the trio loosely patterned the groups of friends that would form today or took shape in the past, each having their share of SK’s and Guri’s and Abhilaash’s. It is further invigorating to incise it as cinema beyond entertainment did Dil Chahta Hai, mapping the three friends to the three-part Freudian personality structure of a human: the ID (Guri), ego (SK), and the superego (Abhilaash). It augurs well here too, for the ID and the superego are the clashing parts, with ego persistently trying to establish a middle ground, or as another of my friends, an aspirant himself, put it: SK’s form the vital part of any group.

Akin to most of TVF’s previous shows, Aspirants too was served to the audience piecemeal, in stark contrast to the shows on other OTT platforms, that allow themselves to be devoured at once, banished, and binged. While the method of serialising a show guaranteed anticipation, it laid a fine line to tread on: ensuring a bind between the narrative of every episode, while maintaining their individual panache. Every episode had to stand out, supersede, or at least match its predecessor. Alternatively, the series had little space for crests and troughs, unlike its counterparts on Netflix or Amazon Prime, where a series could afford to slump and slide in parts, and still retain its collective tempo as a story.

Each episode of the series makes an ostensible attempt to cover a part of the journey of an aspirant: optional subjects, apt teachers, right mindset, fallback options, failure/success; and in doing so, leaves unmissable gaps, so much so that one episode could be delinked with another in the absence of a non-linear narrative structure. Consider this: Abhilash starts off his preparation with a particular concern for his optional subject, and while we are shown an entire episode on him grappling with the same, the theme finds absolutely no mention in any of the remaining episodes. Likewise, for the themes of an apt teacher or right mindset, either of which stays limited to their respective episodes and don’t persist for the entirety of an ‘aspirant’s’ journey. It is amusing and baffling at the same time, for the very fact that all these themes form crucial checkpoints of an aspirant’s route, and while TVF is spot-on when they pick them, they falter in creating a cohesive whole from the parts they pick.

The composition of our lives is riddled with complex and chaotic layers, most often exceeding the people we believe to be the only protagonists of our story, sometimes excluding them in lieu of other temporary presences. Stories then, both ours and theirs, are deeply intertwined narratives, moving in tandem, impressing their drawings upon each other. The story of the triad in Aspirants, too is accompanied by a host of peripheral characters, all of whom singularly grapple with their hardships, while also lending a hand to their peers. In a passing scene, Dhairya (Namita Dubey) and Abhilaash after having spent hours and days in evaluating each other’s answer scripts, the tables turn. Abhilaash’s score has exceeded that of Dhairya, her face turns taut for an instant, before they fondle and erupt into laughter.

For a show that chalks the competitive spirits of students vying for the coveted spot, Aspirants has very few such illustrations of the (healthy and unhealthy) competition that populates the preparatory ring. The said scene, albeit momentary, is telling of the possible tensions that could arise between fellow aspirants and how they could maneuver their ways around the same. Dhairya, however, is not so much of an aspirant as much she is an enabler for Abhilaash’s growth throughout her sequence in the series. The parts of her we’re privy to are limited, and constricted by the developments in Abhilaash’s personal life. Sandeep Bhaiya (Sunny Hinduja), a torchbearer of sorts for Abhilaash, finds a well-rounded character in contrast. His story is emblematic of the inevitable struggles of class mobility in this country, and how the trials to move up the ladder itself come at a heavy cost. Sandeep Bhaiya’s track, after running the viewer through his woes and miseries, culminates in a sobering realisation, made apparent by the transformation of his baritone as an aspirant to a meek accent as a civil servant. Humbled by the uncertainties of life, Sandeep Bhaiya enshrines the lessons of ‘balanced living’ in his restrained tone, paving the way for Abhilaash to end his friction with Guri in the climax.

Each episode of the series makes an ostensible attempt to cover a part of the journey of an aspirant: optional subjects, apt teachers, right mindset, fallback options, failure/success; and in doing so, leaves unmissable gaps, so much so that one episode could be delinked with another in the absence of a non-linear narrative structure.

The climactic moments in Aspirants are a delectable treat, not in the least because of the dramatisations of the scene, but largely due to the verses Deepesh Jagdish chooses to stamp the culmination with. Ask an aspirant, and you realise the weight of Kunwar Narayan’s uplifting words. For a show that is pivoted on ‘relatability,’ Narayan’s poem captures its essence, fittingly and movingly collecting the underlying sentiments of perseverance and grit.

कितना स्पष्ट होता आगे बढ़ते जाने का मतलब

अगर दसों दिशाएँ हमारे सामने होतीं,

हमारे चारों ओर नहीं।

कितना आसान होता चलते चले जाना

यदि केवल हम चलते होते

बाक़ी सब रुका होता।

Another of my friends, again an aspirant, told me how the show ‘doesn’t have any villains and heroes, and is very realistic.’ His praise for the show underscores the elixir of TVF’s enviable run in the web-show realm: a documentary-esque format surrounded by bushes of drama and buds of romance. Either of the three is an inevitable ingredient in TVF’s recipe, complementing and completing the others. In many ways, TVF’s swooning powers are a direct result of the medium it operates on: YouTube almost acts as a stirrer to its recipe, outlining its stories with a shade of an all-encompassing accessibility. It’s free, above par entertainment, available to one and all. The ‘relatability’ as it is then is driven both by the medium and the message, the former drawing audience across the digital landscape of the hinterland, and the latter piquing and holding their interest. Not surprisingly, all the desi shows that have tasted some success on YouTube bank on a close-to-real storytelling zone. It is as much a necessity for the show-makers as it is the democratic character of the platform, where the viewers and creators are not two but one single group that runs the business.

When TVF began its productions in 2011, it was a small bunch of dilettantes, trying and training to be the best possible in their fields. In no time had it established itself as the go-to entertainment channel for the millennia did the gold-mine of its actors become apparent. Slowly and steadily, it became a launchpad for its actors and writers, incubating them for a larger prospect. The list here is long, but betrays remarkable consistency. It is to this effect that actors like Naveen Kasturia could firm a place for themselves, both in the corridors of Hindi cinema and the hearts of the internet age. The finesse of acting coupled with punchy writing remains a trademark of TVF to this day, but the pitfalls are no longer hidden. For massy productions tend to incline towards massy notions, often stereotypes, and open up the story to fall for populism at places. Aspirants steers just clear in this case, managing to dispel the binaries of Plan A vs. Plan B in Sandeep Bhaiya’s poignant monologue towards the end. The caveat, however, continues to loom large as TVF makes more of its type.

Aspirants, despite tiny blots and inchoateness, shines and sparkles. The duopoly of the formative past and a settled-but-unsettling present makes for a resplendent watch, leading the viewer to a three-layered inquisition: of the happenings of now, the occurrences back then, and the bridges between the two epochs. The closure is absent for the bygone period, for we still don’t know how Abhilaash the aspirant came to be Abhilaash the IAS, and it is only the conflicts of the present that achieve a resolution. The raison d’etre of Abhilaash’s resentment with Guri too remains at best obscure, and even as we see their animosity reach a happily-ever-after end, we never come to know the driving factors behind their prolonged coldness, save from their brawl post the results of Abhilaash’s unsuccessful attempt. Perhaps, some bridges will be completed in the seasons to come.

My friend Ani, who had begun his toil for the UPSC CSE the previous year, found himself in a mix very recently. Aspirant’s finale was yet to hit the screens. Ani’s dilemma was a denouement of a series of questions that had itched his mind throughout: the optional subject. There were trends and statistics, opinions and inclinations, all of which led him to arrive at the binary between History and Anthropology. I recall mentioning to him how I’d already seen this puzzle (recall Episode 1), and it occurred to me then how close Aspirants had come to mirror the curve of an aspirant.

An hour after the finale dropped, Ani sent me the exhilarating emoticons of a sobbing face. When I asked him what he had to say about the show, he took a short-while before answering in his characteristic tenor: “Dil ke behad kareeb tha.” On that, the proximity to the inner wells of heart. I realised I couldn’t quip.

***

Raunaq Saraswat's work has been published on News18, Cafe Dissenus Everyday, Kitaab, Active Muse, The Remnant Archive, and Ibaarat. You can find him on Twitter: @raunaqsa.