The Studio as a Canvas: Sanoop P.C.’s Poetry of Impermanence

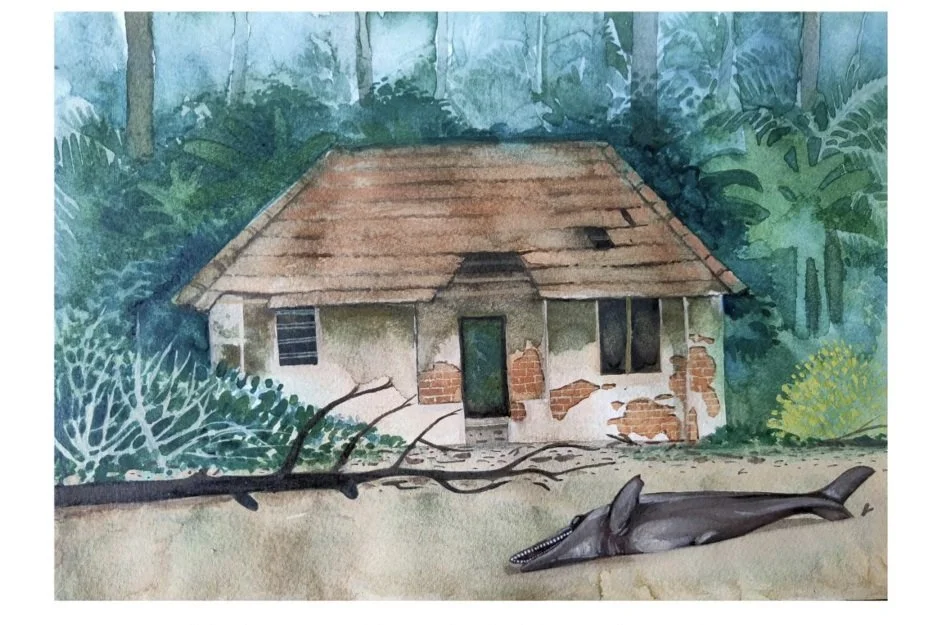

Abandoned House. Image Courtesy: Sanoop P.C.

For his collection “Poetry of Impermanence”, Sanoop P.C. turned his environment in Anchangadi, Kerala into his inspiration, allowing the profound experience where the site of observation is also one of creation.

An artist rents a space in a small seaside village called Anchangadi in Thrissur, Kerala. He decides to live and work from that space, which is a couple of kilometres away from his home. He lives there alone. Occasionally, he is visited by family and friends.

Soon, this new studio space becomes his new home. The landscape here becomes his textbook and reference. Anchangadi is not where his roots run deep, but still, the artist connects to the space through his art explorations. There is a sense of impermanence he already feels about his stay, but that impermanence is as lyrical as a poem.

Sanoop P.C.

Held from November 6-8, “Poetry of Impermanence” was a studio display by Sanoop P.C., a visual artist hailing from Thrissur. Sanoop holds an MFA in Painting from the University of Hyderabad, has been a part of the production design crew in a number of films in Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu and Hindi, and has several group shows to his credit. He was the winner of Kerala Lalithakala Academy Student Scholarship in 2008. During the pandemic period, his works were displayed in online group shows “Soul Space” (2020) and “The Show Must Go On” (2020).

Unlike his other exhibitions, however, the offbeat composition is what truly makes “Poetry of Impermanence” unique. It is not curated inside a gallery, but inside Sanoop’s home-studio. The studio is an artwork in itself, and the artist himself is the curator. To observe the artwork at their site of creation is a profound experience. We feel at home, where the art feels at home, where the artist makes his home.

Sanoop’s studio is well-lit and minimal in its interiors. It is a space on the second floor of a building, partly a residential space, partly a shopping complex. The studio has large windows in every room. The window in the living room opens to the road that leads to the beach. Looking down from here, one sees a school building and a playground on the opposite side of the road. The goal post on this playground was a model for one of the paintings displayed. The reflection on a puddle on this ground on a rainy day is the subject of another painting. The window in his bedroom opens to a few houses standing against the backdrop of tall trees.

Space is a crucial element in much of Sanoop’s work. Here, the artist displays his interpretation of the present space, his interaction with this space and his recollection of his space of origin, the space to which he connects deeply.

Space is a crucial element in much of Sanoop’s work, including “Poetry of Impermanence”. Here, the artist displays his interpretation of the present space, his interaction with this space and his recollection of his space of origin, the space to which he connects deeply. All the works connect to each other and compose a visual poem of the spaces the artist himself has experienced. Sanoop composes this poem mostly using the diction of everyday visuals from Anchangadi.

Further in the studio, there are paintings exhibited on either side of the walls in the living room. In a corner there is a fish tank, but, instead of fish, it contains a terracotta sculpture of a seated human figure and water plants. There are a few Dorodango balls in the tank, too, which have a special significance; Dorodango was used for a collective art experiment conducted by the artist and his family during the Lockdown.

Sanoop looks at the images he comes across from twin perspectives. He tries to take a perspective from inside the space which enables him to understand what these images mean to the people in the neighbourhood. Simultaneously he thinks how someone from outside this space would make meanings out of the same image. The artist analyses his own work and finds how it evolves according to space. Sanoop has said that he observes that the art works based on his place of origin is more conceptual in nature, while the process of painting often becomes prominent in the body of works based on Anchangadi. He thinks this change is related to the depth of connection he shares with each space.

Works displayed in the kitchen are from his series called “Mayiladum Kunnu” and “Nayadi Kunnu”, which are fictional places inspired from real life. These works are rooted in his ancestral village, Thonnalloor, and Sanoop’s native village, Eyyal, in Thrissur. The bedroom hosts a large size oil painting “Visit by Friends” of two friends standing by and enjoying a view of the sea. The artist’s bed, this huge painting, some indoor plants, another fish tank without fishes, a small shelf of belongings and a big window make this room.

Photo courtesy: Sanoop P.C.

In a seaside village, uprooted coconut trees with the roots exposed are a common scene. It is a visual different from the image, people in the mainland relate to the idea of coconut trees. In a work titled “Abandoned House on the Shore”, there is an image of a dead fish. “It is an everyday visual for someone living here,” says Sanoop, “but it would look like a surreal image to somebody who is not acquainted with this space”

For Sanoop, space is much more than memory, geography and aesthetics. His art intensely narrates the politics of space. “Summer in the Sixties” is a painting that converse to the land reform movements in Kerala during the 1960s. The work speaks of the people who were made to stand outside the fence securing land rights.

“In my native place, spaces are still segregated by caste. I grew up watching community gatherings, rituals and folk performances,” says Sanoop. In his series “Mayiladumkunnu” there are multiple references to his native place. Image of peacocks appear in this series often. The peacocks are not painted for aesthetic appeal alone, but their presence signifies a dry landscape where water is scarce.

Sanoop explains his conception of the series “Nayadi Kunnu”: “There are places where even electricity hasn’t made its way yet. I have observed something about such places, even the name of such places appears in the news only if some violent crime happens there. Otherwise, nobody talks about such a space, as if it doesn’t exist at all. It was from this thought that I developed this series”.

An untitled installation made during his MFA time is inspired from a ritual practice of healing among the potter’s community in his village. Terracotta sculptures of the ailing body part have to be offered to the deity. The installation is a heap of small terracotta sculptures of body parts placed under a neem plant, which he grew in a wooden box. With representational terracotta pieces, Sanoop also added sculptures of body parts where he felt pain back then.

Space influences Sanoop’s colour palette and material as well. During his childhood Sanoop used to sculpt in clay. “Clay was easily available in our place, that is why I started from that medium.” In college, he specialised in painting and started using media like oil paint, water colour, ink and charcoal more frequently. More recently, he has been using gouache as the medium. His experience in production design introduced him to more material and possibilities of mixed media.

Visit by Friends. Image courtesy: Sanoop P.C.

Sanoop mentions that is also influenced by popular culture, films, literature and cultural movements. The artist’s palette is tinted by his social exposure. “If you observe my colour palette, you can see that I use a lot of Prussian blue and burnt sienna,” says Sanoop. “This is perhaps the influence of popular movies I watch. The shade of terracotta is also prominent in my works. I think this comes from my childhood memories of watching pottery at craftsmen’s places”. Those memories are mostly attributed to his father, whose profession was dressing laterite stones (cutting and shaping the edges manually for the construction of buildings).

The process itself is articulative in Sanoop’s works. In an untitled mixed media work from 2012, he incorporates a carved, red laterite stone. He relates the act of carving to his father’s occupation. Inside the stone carving, there are forms of skulls made of silicon gum, the proof of ancestral existence and the artist’s roots. The process of carving and digging delves deep into these roots: it is a curiosity to know the ancestors, to evoke his past and his roots.

The process of conception only leads to a powerful evocation from the final images themselves. In Sanoop’s perspective, an abandoned house need not be a sign of deterioration and rejection—it can also be a symbol of searching for a new home and hope.

The process of conception only leads to a powerful evocation from the final images themselves. An eloquent example is the abandoned house in “Poetry of Impermanence”. In Sanoop’s perspective, an abandoned house need not be a sign of deterioration and rejection—it can also be a symbol of searching for a new home and hope.

Sanoop also shared with me a few instances of how the local people of Anjangadi engaged with his art. Many instantly identified the spaces and landscapes he painted. One pointed out the contrast in the landscape seen in “Abandoned House on the Shore”. While the foreground in the painting is a sandy landscape representing the beach there, thick vegetation is painted in the background, suggesting a tropical landscape.

On the day I visited, one highlight of the exhibition was the visit of a young girl, perhaps around ten-years-old, who was there to observe the show all alone. She left and then returned a few minutes later, with her own art work to show Sanoop.

After watching the display, I took the road down to the beach and found the objects, landscapes, and spaces interpreted in Sanoop’s art come alive before my eyes. The display had already been an intimate experience; this stroll along the beach further made this experience a personal one. I found myself connecting the images I came across, to the artworks seen at the display. Even in the poetry of its impermanence, Sanoop’s art, and the landscape of Anchangadi leaves a permanent imprint to all those who experience it.

***

Reema Kurikkalot is a writer, researcher and artist hailing from Kerala, India. Currently she is pursuing her doctoral research at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. She was the artist-in-residence at Nagaloka, Nagpur. Her artwork was displayed in an online group show "Power and Pulp", curated by Rajyashri Goody. You can find her on Twitter: @ReemaKurikkalot and Instagram: @meemitales.