Pardesi Pahadi: Nanda Devi - A glimpse of the Himalayan Goddess

Sunset from Lata Kharak - Photo: Zachary Conrad

“I feel a lot of things in the mountains, but gratitude is what I feel the most.” In his first ‘Pardesi Pahadi’ column, Zachary Conrad writes about an unforgettable hike for a glimpse of the majestic Nanda Devi

Author’s Note: The Himalayas are my favorite mountain range. I know that must sound obvious and banal, like being a Yankees fan, or being really into the Beatles. But they’re more than just the tallest mountains in the world. For the seven years that I lived in Landour, Mussoorie, these mountains were a constant presence, a beckoning horizon I could always look up to, and disappear to whenever I had the chance. These trips into the Himalayas were the best part of my life in India and how I connected with its people and its culture. These mountains are like nowhere on Earth, and I hope to share them with you.

Editor’s Note: Nanda Devi is the second-highest mountain in India, and the highest that is located entirely in the country. At an elevation of 7,816 metres, it is the 23rd highest mountain in the world.

We stepped out of Nandu’s car at the edge of the Dhauli Ganga in the Niti Valley, and shouldered our bags for the short hike from the road up to Lata Village. It was early: the morning sunshine had yet to reach the riverside and had only just kissed the stone-roofed houses of the village, but already, men and women were hiking back from the fields with enormous bundles of daal or millet tied over their shoulders. Everyone overtook the three of us except for one older-looking man, wearing chappals despite the cold, who, unperturbed by his load or the grade of the path, engaged Nandu in conversation and walked alongside us, until we reached the village some 20 minutes later.

“Aapko chai chahiye?” (Want some tea?), Nandu asked Ian and I. We politely declined, and then found ourselves sitting in the sun, drinking the inevitable cup of tea. It was late October, and the school where Ian and I were working at was on mid-semester break. A friend of a friend had connected us with Nandu to help arrange our trek. We had made the long drive from Mussoorie to Joshimath the previous day and were looking forward to stretching our legs. Village dogs came over to see if we would share our biscuits, and children gave us surreptitious glances from around corners and through doorways. When our cups were nearly emptied, the old man from the path returned in a hurry, brushing his teeth and gathering his things. As he shook out an old sleeping bag it occurred to us that he was going to be our guide.

Lata Village. Photo: Zachary Conrad

Nandu introduced him as Raghubir Singh. “Bill Aitken is my friend,” Raghubir told us. “You’re from Mussoorie. You know Bill Aitken?” Raghubir, we learned, was the same man whose heroics were chronicled in Aitken’s wonderful book The Nanda Devi Affair. He had prudently switched out his chappals for some Chinese-made canvas sneakers and had packed away a kit that would make any fast and light hiker jealous. In keeping with the Pahadi way of doing things, he wore all the clothes he would take, except for a rain jacket he rolled into a closed foam sleeping pad, along with a sleeping bag and a woolen monkey cap. With a scarf, he tied this all neatly over his shoulders like a backpack. We were ready.

Our trek into the Nanda Devi Sanctuary began aptly with a puja to Nanda Devi herself. Raghubir broke a coconut on the heavy flagstones to offer as prasad and adorned our foreheads with vermillion paste, marigold petals, and rice. Like most of the people from this region, Raghubir has a deep reverence for Nanda Devi. Though known as the bliss-giving goddess, she is equally harsh and terrifying when provoked, like the mountains themselves. Nanda Devi could bestow on us unparalleled joy or hardship according to her whims. This puja was to ask for permission and safe passage as we ventured into her realm.

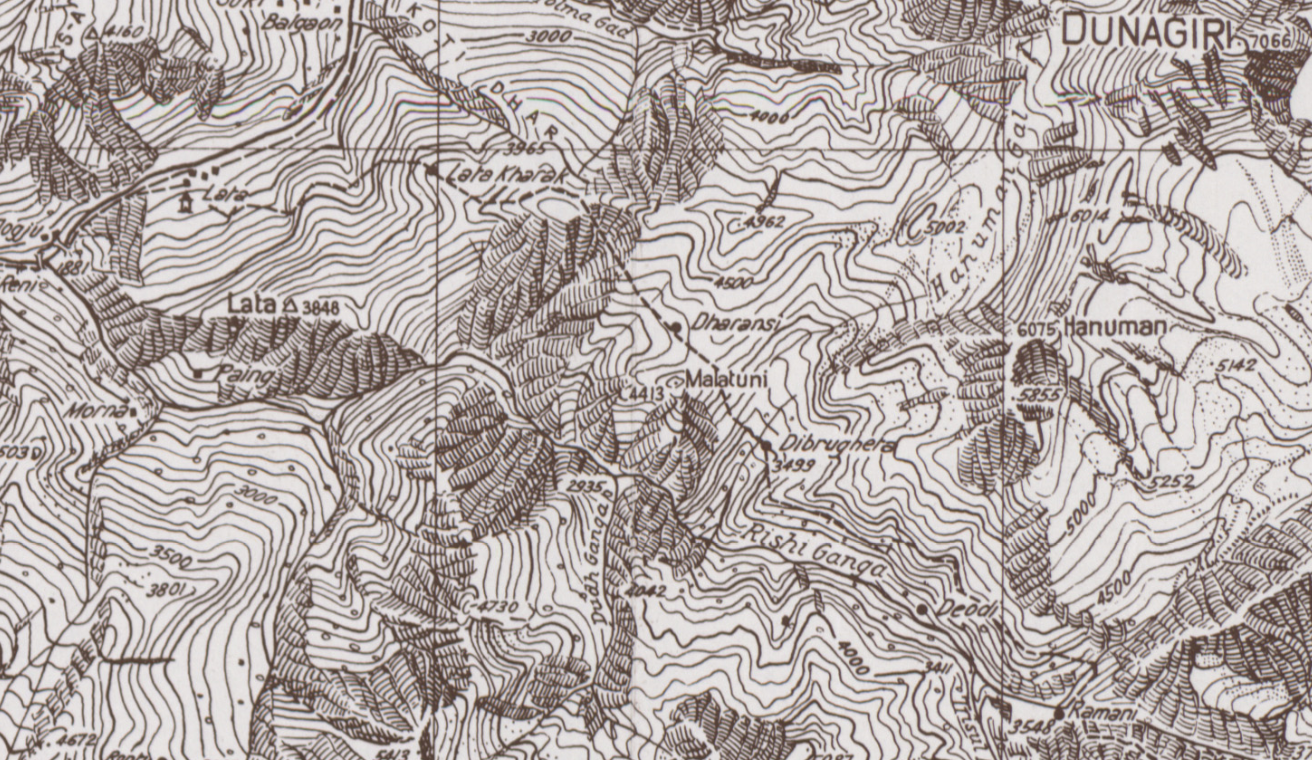

Nanda Devi is ringed by a fortress of jagged summits 6000-7500 metres high, broken only by the Rishi Ganga Gorge, a steep, narrow canyon so-called because the Saptarishi are said to have retreated this way, where nobody could follow, to practice their meditation in peace. Nobody entered the inner sanctuary until British mountaineers Eric Shipton and Bill Tilman, with Sherpas Angtharkay, Pasang, and Kusang opened a route through the gorge in 1934. This is the route we followed, and it is still the only practicable way into the sanctuary. In the 1970s many climbing teams came to try Nanda Devi and other peaks within the sanctuary walls. This provided good work for men like Raghubir, who worked on many expeditions as a porter in this time, but with a heavy cost to the environment.

Like most of the people from this region, Raghubir has a deep reverence for Nanda Devi. Though known as the bliss-giving goddess, she is equally harsh and terrifying when provoked, like the mountains themselves. Nanda Devi could bestow on us unparalleled joy or hardship according to her whims. This puja was to ask for permission and safe passage as we ventured into her realm.

The narrow access route had become so degraded that a total ban on human activity in the sanctuary was enacted in 1983. Soon after the area was designated a national park, and then made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988. This was good for the kasturi and the bharal, but tourism had become an integral industry to people in the Niti Valley since the Sino-Indian war ended trade with Tibet in the 1960s. Local people petitioned hard to have some control over the management of the park. From 2003, limited trekking has been allowed: trekkers are required to travel with a local guide, and may only go as far as the hanging valley of Dharansi.

The first day’s trek was a short, steep climb through spectacular deodar forest up to Lata Kharak, an alpine meadow just above the tree line. It felt good to be hiking. The air was cool and smelled like trees. At camp, Raghubir seemed satisfied with our effort, commenting that our bags were heavy and that we were stronger than we looked. Most treks in the Himalaya are still done “sahib-style” with a support team of porters and cooks, and I’m often met with curious surprise for choosing to cook and carry for myself. After we established camp, Raghubir went off to eat and chat with some friends who were returning with a group of two Polish hikers. We cooked a quick dinner of nutri mac & cheese as the sun and the temperature sank. A hard frost greeted us the next morning as we prepared for the difficulties ahead.

The trail climbs steadily from Lata Kharak to the ridge of Jhandi Dhar. From here, snow covered the ground and Dunagiri loomed large in the northeast. We continued climbing, up to another ridge running roughly north/south. Here the landscape changed abruptly. As we crossed to the south side of the ridge, the path clung precariously to rugged cliffs. I could easily reach out and touch the mountain to my left side as the slope fell away sharply at my right, and once I hung a foot over the edge just to feel the combination of thrill and dread in the pit of my stomach. Fortunately, the geology here angles the rock into the cliffside, not out. It would be hard to fall off, but it would probably be the last thing you ever did. We made our way carefully along the edge of the gorge, dutifully kicking steps in shadowy places where snow still hid, and using our hands on some of the steeper traverses. A final stretch of steep, snowy trail brought us over the Dharansi Pass where we caught our first glimpse of Nanda Devi.

The Rishi Ganga Gorge. If you dropped something down there, would you go after it? Photo: Zachary Conrad

We sat and enjoyed the view while Raghubir helped another trekking group descend the steep and snowy section we had just crossed. We took a few pictures then continued along the cliff edge toward Dharansi. This is the most spectacular section of the trek: Dunagiri, Hanuman, and Nanda Devi dominate the skyline straight ahead, with Trisul and Nanda Ghunti off to the right. Rishi Ganga churned some 2000 metres below our feet as the narrow path snaked along the cliffs.

We had nearly reached the end of this treacherous section when Raghubir’s foam pad got hung up on a rock as he rounded a corner. It twisted and bent, and before we could do anything to stop it, Raghubir’s sleeping bag shot out and over the edge. We watched as it fell, landed on a slope over a hundred feet below us, and then tumbled some more. There was one moment when it looked like it might come to rest as it moved up a small hillock, but it just launched over the edge like a ski-jumper further into the abyss.

A stern look of disappointment came over Raghubir’s face, but only for a moment. “Koi baat nahi,” he said, No problem. Without looking back, he continued onward. Ian and I talked about what we should do. It was still relatively early, and we had time to return to Lata Kharak, or even to the village, which seemed like the smart thing to do

Raghubir continued on for about ten minutes to a place called Ranikhola where the cliffs end and the Dharansi meadow begins. He took off his make-shift backpack and his hat.

“You guys go ahead to the camp, he said,” pointing to a flat spot near a collapsed shepherds’ hut in the distance. “I’m going to get my sleeping bag.”

We tried to talk him out of it, of course. It seemed hopeless. And dangerous. And foolish. “You don’t have to get it,” we said. But he insisted on going, and who were we to say no? Raghubir had been going into these mountains since before we were born. He knew what’s possible, and what was crazy.

“Do you want someone to go with you?” I asked.

Chaukhamba and Neelkantha in the morning light. Photo: Zachary Conrad

Raghubir laughed. “That would be dangerous.”

So, helplessly, we watched him downclimb, deeper and deeper into the gorge. Soon Raghubir was out of sight. We had to trust his judgment and hope he would be back soon.

I hiked alone to a small mandir high on the ridge to watch Nanda Devi greet the day. Out to the west, Chaukhamba and Neelkantha glowed orange in the dawn’s first light. I gazed to the mountain with a feeling of peace and contentment that belied the stinging numbness in my toes.

About an hour later, we reached camp. It was getting cold. We put on jackets and put up tents and started cooking. First chai, then dinner.

The chai had just come to a boil when Raghubir returned, faster than we had even hoped, and with his sleeping bag, too! Amazed that he was able to recover it so quickly we pressed him for details, but he would only say it was very far and very steep. He puffed on a beedi - spiked with chaaras - holding it between his middle and ring fingers, and sucking the smoke from his cupped hands the way shepherds do. When he finished, he took us to collect water from a hidden spring up and over the ridge. From here, we could look down upon the small meadow Dibrughera into the upper Rishi Gorge, where Shipton and Tilman’s route ventured, and greater challenges lay.

Raghubir called out to a herd of bharal on the slopes above in a kind of wild-man’s gibberish, laughing as they scattered and ran. I couldn’t help but admire him. He wasted no energy feeling angry or sorry for himself after dropping his bag, or waste any time wishing it hadn’t happened, like I would have done. He seemed impervious to fear and doubt as he ventured into the canyon and did what needed to be done. Now that it was over, he had left the entire ordeal behind him.

Nanda Devi at dawn - Photo: Zachary Conrad

Raghubir knew what I could only intellectualize: you cannot argue with a goddess. When she gives you reason to be joyful, you be joyful. And when there’s work to be done, you get to work. Anything else, wishing things were different, fearing the future or regretting the past, is extra.

We passed a cold night huddled in our sleeping bags and woke up before dawn. I hiked alone to a small mandir high on the ridge to watch Nanda Devi greet the day. Out to the west, Chaukhamba and Neelkantha glowed orange in the dawn’s first light. I gazed to the mountain with a feeling of peace and contentment that belied the stinging numbness in my toes.

I feel a lot of things in the mountains, but gratitude is what I feel the most. I said thank you to the mountains and hurried back to camp. As we hiked back to Dharansi pass I couldn’t help turning back, again and again, to get one more glance, one more photo of Nanda Devi. The path on the other side was still coated in ice and I made my way down slowly, clumsy and afraid, doubting my feet and wishing for crampons or an ice ax. Raghubir strolled along the same path serenely, his hands folded behind his back, like the ice wasn’t there.

We returned to Lata village that evening and found the whole village preparing for festivities. Nanda Devi was out of her mandir, and in the village square, wearing fine robes. Two rams had been slaughtered and cooked for a communal prasad. A feast was about to begin. First plates were handed out, then glasses of homebrewed millet beer and daru. As night fell, we linked arms and danced in a circle, and the people of Lata joined their voices together in a song I didn’t understand. The singing and dancing and drinking continued late into the night and showed no signs of slowing as I snuck off to bed.

Raghubir Singh, our guide, at Ranikhola. Photo: Zachary Conrad

Early the next morning, as we left to catch the 5:00 am bus to Rishikesh, we shared the path with village women returning to the fields to collect the last of this year’s harvest. Raghubir has come to see us off, and we thanked him one last time.

Back home in Mussoorie, life resumed its familiar routine with classes to teach and papers to grade, and I was back to gazing at the Himalaya, plotting my next foray. On most days, it was easy to see the twin summits of Bandarpunch, broad flanks of Chaukhamba, and pointed spires of Swargarohini from anywhere on the Chakkar in Landour. But Nanda Devi was more elusive: Far and to the east, she could only be glimpsed from a few select points, and was often obscured by the rising sun in the morning and haze later in the day. Like all the best things, a view of Nanda Devi required effort, planning, and luck.

It’s always a thrill to see her.

***

Zachary Conrad is a teacher, hiker and climber. Raised in the woods of Vermont, Zachary spent 8 years in the Himalayan foothills of Landour, Mussoorie. He is now based in Guiyang, China. You can follow him on Instagram: @zachonrad