Lost Women and Found Freedoms

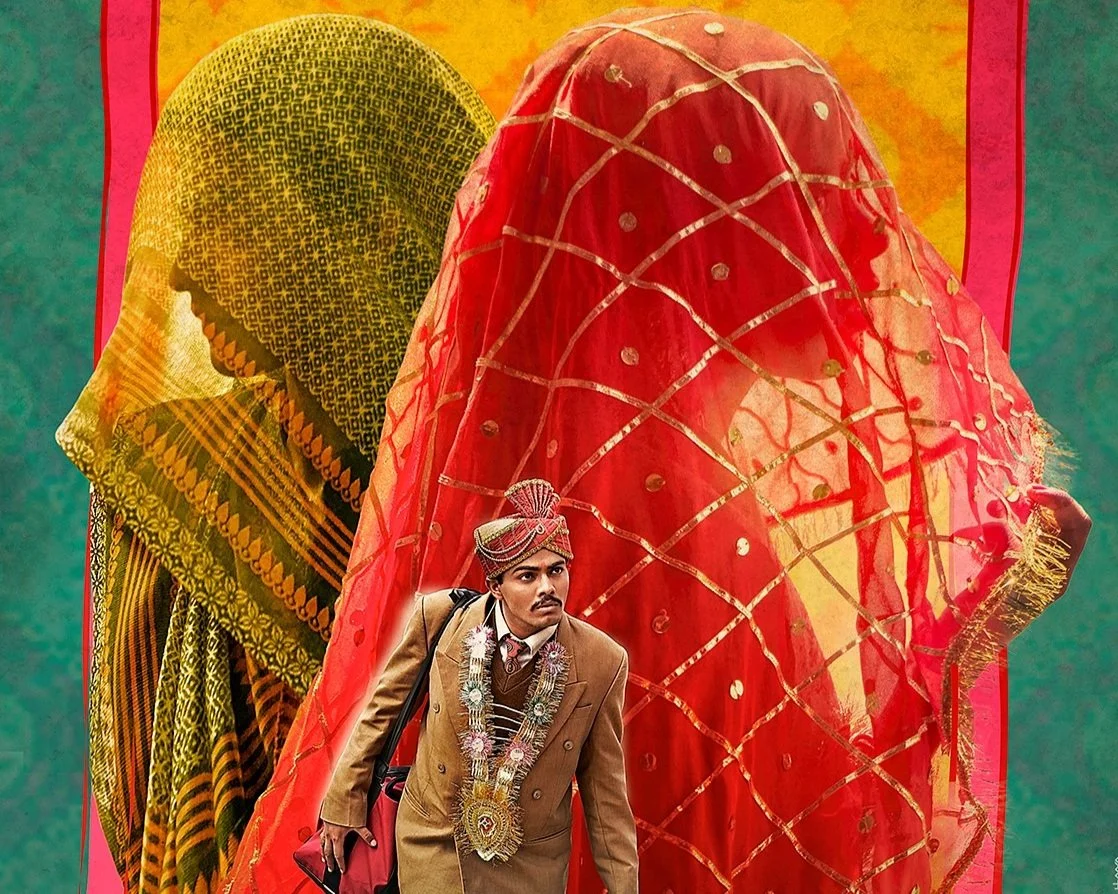

Kiran Rao’s Laapataa Ladies (2024) is a film that makes serious societal commentary on the socio-cultural, economic, and governance aspects of women empowerment, wrapped within a multi-layered satire.

Since it was released on Netflix earlier this year, audiences in India and across the globe have been enraptured by Kiran Rao’s soulful and thought-provoking Laapataa Ladies (2024), a film that offers a profound message on deep-rooted socio-cultural and economic aspects of women’s empowerment in sub-urban India. The film wraps serious societal facets within a multi-layered satire, helmed by memorable, scrupulously-built characters. Recently, Laapataa Ladies was submitted as India’s official entry in the International Film Category at the 2025 Academy Awards.

In their article “Laapata Ladies and the Importance of Being Lost” (Economic and Political Shivali Tukdeo and Mizaj K V responded to the film’s central themes, specifically emphasizing on the significance of education, veiling-induced cultural orthodoxy, and early marriage in the context of women empowerment. The authors articulated that, “Education is probably the most common means by which young women can delay marriage.”

Though there is no denying of the fact that education is the key factor for upward socio-economic mobility (especially for women) this piece reflects on various socio-cultural, economic and governance aspects related to women empowerment that the movie exerted, which are: socio-cultural orthodoxy related to marriage, dowry and education, female labour force participation, trust deficit in societies, protection of agricultural labourers, as well as productions without sacrificing its nutritional values, and various related governance issues and challenges.

The dimensions of gender inequity are uneven across rural and urban areas in India. It is widely acknowledged that early marriage—tightly rooted in gender inequality—curbs the socio-economic development of women. A variety of research has found that the incidence of early marriage is positively associated with spousal violence which affects their mental health and various aspects of physical health, and negatively associated with female labour force participation. As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2022-23) data, female labour force participation rate (LFPR) was substantially lower with 31.6 per cent, as compared to male LFPR (77.4 per cent). According to National Family Health Survey-5 for 2019-21, 27 per cent of women age 20-24 years married before age 18 years in rural India, compared to was 14.7 of the same age range in urban areas. Drive by societal pressure, conformity to early marriage is a major impediment to resilience against patriarchy, which should gain urgent attention among the society and the government at various levels.

This is where Laapataa Ladies has played a remarkable role in documenting how marriage can culturally become the topmost priority of a girl’s life, and how, from a young age, families prepare girls for domestic role through engaging them in household activities, without even a marginal attempt of imparting lessons on life skills outside of it. The film also showcases the tightly-rooted practice of dowry (which is prevalent in some parts of India), which gradually goes up for tying the knot with ‘economically stronger’ husband, irrespective of his human qualities.

Through the wayward story of its characters, Rao’s film elucidates how even a little time away from that social pressure can become a life-altering experience for some women.

The plot centres on two contrasting newly-wed brides: Phool Kumari (Nitanshi Goel) and Jaya (Pratibha Ranta), who go missing during a train journey. After a series of adventures, both titular “Laapataa Ladies” do arrive at ‘desired destinations’: Phool is reunited with her husband, whereas Jaya parts ways with the man she’s wedded to, to pursue her education. In between this, a series of events befell that have been stirring as well as reminding concerns about the gendered progressiveness of Indian society, even after 77 years of Independence.

Veiling is widely recognised as a major deterrent to women’s empowerment, since it is a sign of female subjugation in many corners of India. Laapataa Ladies light-heartedly flags this aspect as a reminder to society, to revisit this cultural orthodoxy. The culturally-accepted practice of using ghoonghat (veil) was the foremost factor behind the mix-up of both the brides from the train, as Jaya ends up with Phool’s husband Deepak’s family, while Phool is left lost and despairing at an unknown train station (Pateela), waiting to get reunited with her Deepak (Sparsh Shrivastav).

Living with Deepak and his family, Jaya begins to find a place of comfort. She befriends Deepak’s sister-in-law Poonam (Rachna Gupta) after recognizing her natural talent of drawing, using which, she even makes a poster of the “Laapataa” Phool Kumari. Seeing thebond between Jaya and Poonam, Deepak’s mother Yashoda (Geeta Aggrawal Sharma) feels the significance of ‘friendship’ as a key component of any relationship. Yadhoda admits that she has forgotten what she really likes to eat, since she only cooks food preferred by the men of the house. She wonders, “Toh kya ab auraton ke pasand ka khana banega?” (So will the food now be cooked of women’s choice?).

Jaya also shares her knowledge of organic farming with Deepak’s father, to help protect the agricultural produces at his farm from pests, without sacrificing its nutritional values. She recalls how her own father had been forced to sell off all his land, a memory that motivates her interest in agriculture.

Meanwhile, Phool learns to live and work on her own alongside Manju Mai (Chhaya Kadam), a woman who independently runs a food stall at the railway station. Manju Mai believes that Phool’s husband has wilfully dumped her. She explains how women in this country are culturally being duped since long back in the name of “Bhale ghar ki bahu-beti” (Women of respectable families).

Phool begins working with Manju Mai at her food stall, and realizes that women can work as well. Why, she wonders, are girls not given the same opportunity to be financially independence as men? “Dekh Phool,” Manju Mai replies, “Aurat anaj uga bhi sakti hai paka bhi sakti hai. Bachcha paida bhi kar sakti hai bada bhi kar sakti hai. Dekhne jaye toh auraton ko mardon ki kono khaas zaroorat waise hai nehin. Par yeh baat agar auraton ko pata chal gayi to mard bechara ka baaja na baj jayega. Ab samjhi ka “fraud” chal raha hai? (See Phool: Women can farm and cook. Women can give birth to children and raise them as well. If you think about it, women don’t really need men. But if the women figure this out, men would be screwed, wouldn’t they? Now do you decipher how “fraud” has been ensuing?).

As Jaya enlightens, Phool receives enlightenment. Ultimately, being lost turns out to be a boon in disguise for both brides.

Thereafter, Manju Mai gives a hundred rupees to Phool, the first income that the latter has earned, for her preparation of a sweet dish for Manju Mai’s stall. This moment inspires Phool, and she imagines the thought of opening a business with her husband, once they are reunited. It is intriguing to note, however, that this moment doesn’t make Phool consider a life without her husband.

Tukdeo and Mizaj’s article has also been motivated by the recognition of the fact that while the ‘trust’ component among citizens in societies influences their choices to sustain livelihoods, the choices out of compulsion made by them can often in turn affect the balance within society. Pervasive trust deficit in India is a major concern, and this ‘qualitative’ factor bears enormous economic implications. The role of effective governance becomes critical in this regard. This suggests the significance of effective service provisioning of education, healthcare, employment opportunities and various other social security components.

Laapataa Ladies concisely touches upon this ‘trust-induced’ unhappy fact of society through Abdul, a man who pretends to have a disability at the Pateela station. Phool is flabbergasted when Abdul reveals his reality. Seeing her reaction, Chhotu, another of her new friends, says, “Yeh duniya bahat hi ajeeb hai. Yahan jo jaisa dikhta hai waisa hota nehin, aur jaisa hota hai waisa dikhta nehin hai" (This world is very strange than appears at first sight. Here what appears is not what happens, and what happens is not seen).

As Jaya enlightens, Phool receives enlightenment. Ultimately, being lost turns out to be a boon in disguise for both brides. A conversation between the two women in the end beautifully summarizes the film, as Phool tells Jaya that “Aap nehin hoti toh hum kabhi na milte” (If it hadn't been for you, I would never have been found).

Jaya replies: “Agar tum nehin hoti na, toh humko hum nehin milte” (If it hadn't been for you, I would never have found myself).

As the efforts of men like Deepak and inspector Shyam Manohar (Ravi Kishan) illuminate, the act of eliminating patriarchy needs a strong resilience against it, which could be achieved through the joint efforts by the men and women both—and certainly not through the conflict of men versus women. Rao portrays these complex themes through detailed scenes, a gripping narrative and astounding cinematography. Resisting the urge to be preachy, the director presents a heartwarming journey, with powerful lessons on various key aspects on women empowerment and associated socio-economic issues across the country.

The author wishes to thank Lekha Chakraborty and Sk. Md. Azharuddin for their helpful comments.

***

Kaushik Bhadra is an Economist with Ph.D. and 15+ years of experience in academic and policy research, and advocacy with various national and international organizations such as UNICEF, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), UNDP, University of California and San Diego (UCSD), Haryana 6th State Finance Commission etc. His areas of specialization and interest within the broad scope of economics are public finance and policy, fiscal federalism, decentralized public service delivery of merit goods, public health and sports financing. You can find him on Facebook and LinkedIn.