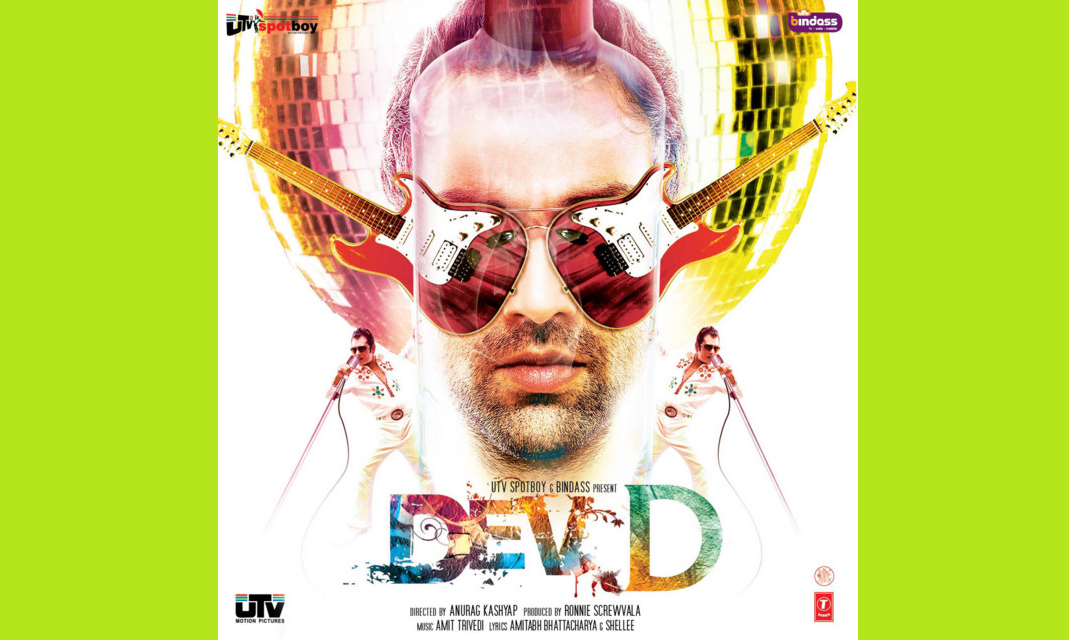

‘Meetha Sa Chara Hai Bukhar’: The Timeless Musical Fever of DEV.D

The music of Dev.D—produced by Amit Trivedi—still sounds fresh and imaginative, honouring Indian traditions while pushing the envelope of a global sound, remixing this popular tale with a burst of enigmatic new energy.

At first, I remember being annoyed. They’re doing a ‘Devdas’ again?

It had only just been seven years since the 2002 adaptation of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s popular Bengali novel. The 2002 Devdas—directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali and featuring Shah Rukh Khan, Aishwarya Rai, and Madhuri Dixit—was the most expensive Indian film ever made at its time, a flood of gold, glamorous period outfits, devastating drama, and popular songs that were played at every wedding sangeet for the better part of the 2000s.

Devdas was a massive hit. But for me—a mere teenager at the time—the maximalist period film was simply too much melodrama, and not enough fun.

So, when they announced Dev.D in 2009, I had little interest in yet another iteration of this ‘post-romance’ tale. I knew it too well. Apart from Bhansali’s Devdas, I had read a Hindi translation of the 1917 novel in High School, and seen the 1955 film adaptation (starring Dilip Kumar), too. All great works of art. None of which I wanted to experience again.

And then, I experienced “Emosanal Attyachaar”—the first song released from Dev.D’s soundtrack.

I admit, I was a little confused at first. What was happening? The sound was so familiar, yet something so radically different. There was an infectious vigour about the music—nostalgia and familiarity spiced with a hint of exciting uncertainty—that made “Emosanal Attyachaar” a cult classic.

In Dev.D, Trivedi experimented with playful and brilliant fusions of Punjabi, folk, ghazal, modern rock, hip hop, jazz, waltz, dance, pop, and more… and yet, he managed to provide a uniform conceptual thread connecting the sound of the entire album, a structure to keep the chaos together.

The song immediately signalled director Anurag Kashyap’s intent of this new Devdas adaptation, of Dev.D taking a popular folk tale and remixing it upside down with a burst of enigmatic new energy. It was the mainstream arrival of music producer Amit Trivedi, who helmed over the entire soundtrack, resulting in one of the most iconic Bollywood albums ever made.

In Dev.D, Trivedi experimented with playful and brilliant fusions of Punjabi, folk, ghazal, modern rock, hip hop, jazz, waltz, dance, pop, and more… and yet, he managed to provide a uniform conceptual thread connecting the sound of the entire album, a structure to keep the chaos together. On the tenth anniversary of the film, Devarshi Ghosh on Scroll hailed the soundtrack among some of the great original ‘concept albums’ of modern times, writing, “in isolation, each song will elicit different responses. But together, the whole of the Dev.D album is telling a story with music and lyrics”.

I was heavily impacted by Western music in my teens—rock, hip-hop, and more—and lost some of my tethers with the popular film and Hindustani music that I had been initially raised on. One of the reasons why I instantly grappled on to the Dev.D soundtrack was its expert fusion of the two worlds: the clear influence of rock, hip-hop, and techno on the otherwise firm folk Indian roots of music. It was an album that helped me complete the roundabout to appreciating the classical influences on Bollywood pop with sprinklings of popular Western sound.

Dev.D ushered in new vibes to Indian cinema in terms of storytelling and production, and both Kashyap and Trivedi strengthened their roots in the Indian film industry in the years that followed: Kashyap with his magnum opus, the gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; Trivedi with his work on a number of popular soundtracks in recent years, including Wake Up Sid, Aisha, Udaan, No One Killed Jessica, Lootera, Udta Punjab, Dear Zindagi, Secret Superstar, Pad Man, Bhavesh Joshi Superhero, Manmarziyaan, Qala, and more. This month—some fifteen years since Dev.D—Kashyap returns in another collaboration with Trivedi: the ambitious new musical Almost Pyaar with DJ Mohabbat.

But the news about Almost Pyaar only made me nostalgic for Dev.D, a modernized, existential Devdas for my generation, where each element under Kashyap’s umbrella synchronized together to complete a perfectly-executed orchestra. Kashyap’s direction, the story by him and Vikramaditya Motwane, Abhay Deol’s portrayal of youthful malaise as Dev, the strength and agency given to both female leads—Paro (Mahie Gill) and Leni/Chanda (Kalki Koechlin)—the settings from rural Punjab to seedy New Delhi, a hearty sprinkling of humour, and iconic one-liners that my friends and I quote to each other to this day.

Dev.D was released when I was experiencing the freest phase of my own life: a time in my mid-20s. It was a time when I had decided to take some time off from work to travel alone around India, without a clear itinerary, simply drifting from place to place, making mistakes, and aching a minor heartbreak. By now, I had built a shield of resistance around myself to block new emotional attachments. My own version of “Mahi Mennu Nai Karna Pyar”—I don’t wish to love—a personal wall of disguise and resistance. It was, in hindsight, a pretty common ‘coming of age’ existential crisis: of a life of relative privilege, but one without any strong purpose or definition for self.

And it was this very feeling of hopelessness—or the lack of a feeling—that impacted me with Dev.D. The film is as much a progeny of 20th century European existential/nihilist literature as much as it is a contemporary inspiration of the Indian Devdas story. Kashyap/Deol’s Dev builds a wall around himself after his heart is broken (through some fault of his own) by his childhood sweetheart, Paro; he drifts and spirals into addiction, into recklessness, into a life that seemingly has no purpose any longer.

But this pretend emotionlessness is dense with the weight the absence of emotion. It’s a piece of perforated paper shielding one from facing one’s own demons. It’s Camus opening L’etranger with a nonchalant death of his mother: an omission of sentimentality that is a mask for greater individual emptiness.

The introduction of Trivedi’s music to these themes, however, proved to be a game-changer. Kashyap admitted that hearing the songs made him rewrite the entire film as a musical. The soundtrack—including songs written and performed by a creative group of artists like Amitabh Bhattacharya, Shellee, Tochi Raina, Shilpa Rao, Anusha Mani, and more—elevated Dev.D into the mainstream, far beyond the ‘underground’ status of Kashyap’s preceding films.

Dev.D’s soundtrack brought a deft touch of lightness and humour, turning melodrama into tragicomedy, and shaping the film as an ironic wink at the legacy of the Devdas story. It became the Devdas that my generation sorely needed, a generation that interpreted and expressed sentiments in different ways, a new generation of troubled Devs, Paros, and Lenis.

We accepted Dev.D for being “cool enough” for us; but it was only a new mirror to hold up to our insecurities. The music and the lyrics made it almost acceptable for many of us—walled in behind our self-deceptions—to relate to the film’s themes, without actually having the poetic courage to say so for ourselves. The film offers clear commentary about toxic masculinity and about men objectifying women as merely objects of desire and obsession: women whom they blame for their own insecurities when those desires aren’t fulfilled. Khan’s Devdas was an object of pity for his obsessions. Deol’s Dev didn’t let the man earn our pity so easily: instead, in him, we see a confrontation of the flaws of many more men.

Trivedi took those complexities and provided a musical response to parallel the film’s emotional themes—not just for Dev’s character, but, importantly, for Paro and Leni, too: for their motivations, for their angsts, their emptiness. Like the film, the soundtrack is also somewhat divided between songs that respond to each main character: the earthy, old-fashioned folky mood of Paro; the tepid, waltz-inspired optimism of Leni; the rock/techno angst of Dev.

Sung by Labh Junga, “Mahi Mennu” begins with strings and rhythm to set the mood of Paro/Dev’s Punjabi farm roots. But, very early in the track, the music is quickly interrupted by a record scratch and a slight introduction of a synth, making it clear that the music—like the movie—is about to subvert all our expectations.

This pretend emotionlessness is dense with the weight of the absence of emotion. It’s a piece of perforated paper shielding one from facing one’s own demons. It’s Camus opening L’etranger with a nonchalant death of his mother: an omission of sentimentality that is a mask for greater individual emptiness.

“Mahi Mennu”—along with tracks like “Emosanal Attyachaar (Brass Band Version)” and “Dhol Yaara Dhol”—could fit at any celebratory occasion, but a little attention to the lyrics reveals a disconnect in the transmission. After all, which wedding announces, first with some glee and then with some angst, that “No, I don’t want to love.”? Junga in “Mahi Mennu” sings of the afeem-like ‘nasha’ (addiction) of his beloved, but sings so in a happy tone, or a voice of playful resistance, one that—it soon becomes clear—is only a facsimile of happiness to conceal the inner pain.

That mask wears off course, as the singing soon turns into a desperate crooning by the end. “Mahi Mennu Nai Karna Pyar”. I really don’t want to love.

The aforementioned “Dhol Yaara Dhol” reintroduces feelings of spring, rebirth, and joy. Performed by Shilpa Rao, it’s a hopeful track that preludes a life of joy after marriage, a happily ever after. “Hikknaal” is another fun, Punjabi party song, incorporating a number of stereotypes of timeless Punjabi hits in its ad-libs, with dholaks and twinkling synths to provide support, and an unforgettable sudden introduction of electric guitar to shake us out of our lull.

The celebratory, wedding mood of the album peaks, of course, with “Emosanal Attyachaar (Brass Band Version)”, a glorious composition of the marching brass bands to electrify any shaadi procession, trumpets and dholaks and tubas and more. The song begins with traditional booming trumpets, the boisterous energy of the excited performers, the occasional comedy and gibberish in the lyrics, meant to be consumed in the nonsensical chaos of a (possibly) drunken baraat. (For a decade, Trivedi and the lyricist Bhattacharya performed the song under the nom de plume ‘Band Master Rangeela and Rasila’, fictitious singers from Himachal Pradesh.) It becomes clear quite early that Bhattacharya wrote the lyrics with all filters turned off, having a rollicking good time in its composition—and the listener can’t help but having a hell of a party, too. “Ek, do, teen, char, chhaaaaay!” One, two, three, four six!

Like the missing number ‘five’, it’s clear that something about this wedding is a little different, a little off-key. Perhaps all weddings are a little off-key—and “Emosanal Attyachaar” only makes those absences feel present. The throwaway ad-libs and English words—written and performed with accented, and imperfect English—add to the chaos and uncertainty. Tragedy… Tragedy! You are never sure what you will hear next. You love being at this party, but you have no clue how it will end. Is this what a marriage feels like?

Soon, there will be the surprising, aggressive hilarity of “Bol bol, why did you ditch me, whore?”, and a wakeup call to reality in midst of the celebrations, “Sapne Dekhe Jannat Ke Par Mitte Mein Mil Jaye” reminding us that this is all, perhaps, just a fever dream. There’s no heaven, just dirt.

About 40 seconds in, “Paayalia” turns into a dance number, with drums urging you to keep pace, move forward to the future. There aren’t any glittering gold palaces where Devdas finds his consorts. These are the gullies of Paharganj, and she isn’t your grandfather’s Chandramukhi.

The juxtaposition of musical celebration and lyrical angst continues with “Duniya”—sung by Trivedi and performed by Bhattacharya—where the familiar sounds harmonium and classical Indian instruments are scratched, interrupted and remixed. There are repetitions and spiralling highs and lows. Like the ‘duniya’ itself—our world—the song takes a groovy tailspin, going round and round, “gol gol gol…” The lyrics here, too, feel nonsensical at first, but the incoherences pile together to give it all a beautiful jagged new structure. A heartbreak song mixed with the conspiracies of the world, all signalling to one’s own pitiful misfortunes.

The song “Aankh Micholi” begins with a feeling of doom and darkness, and rolls into something fast-paced, fun, and still somewhat menacing. It’s a combination of ghazal, folk, and techno, coming together for another lamentation about the misfortunes of life.

My favourite song from this album, and perhaps, my favourite Bollywood song ever, is “Pardesi”, performed by Tochai Raina and written by Shellee. It’s a crooning pop number, sprinkled with hints of hip hop and dance, mixing modern electronic sounds with tabla, and that wonderful sitar arrangement that still takes my breath away. It’s folk music meeting the future. Like “Emosanal Attyachaar”, “Pardesi” shines in its ability to nurture a controlled form of chaos, an acceptance of slight dissonance.

“Pardesi”, at its heart, is a song about foreignness, about not belonging, or unrequited love. It’s a song to dance to, a song to feel contemplative too, a song to zone out and drive to all alone. The chorus, “Meetha sa chara hai bukhar…” continues the soundtrack’s themes of flavouring the romantic with the ironic. Love, here, is sweet, but it’s possibly a dangerous fever as well.

That fever reaches its angry zenith with “Emotional Attyachaar (Rock Version)”, performed by Bonnie Chakraborty, the lead singer of the band Krosswindz. More than merely another ‘version’ of the popular track, this song is an underrated classic, filled with guitars, drums, and mayhem, a true Indian rock anthem of heartbreak and angst. While the original “Attyachaar” masks its angst with joy, this one allows listeners the release they’ve craved, an unbottling of all their pent-up rage.

The song begins with soft “wooo wooos”, and an inviting, light keyboard, before the floodgates open. The drums and guitars enter the scene, a warning of a volcano about to erupt. A frantic, quick beat to get the heartrate pulsing. And then, a protest to be left alone. “Hat Jawe Nazron Se!” Get out of my sight!

The heating pressure cooker finally explodes with a visceral scream—accompanied by raging drums—about two-thirds of the way into the song. Chakraborty allows listeners to feel the tremors of his pain when he scream-sings, again, “Aankhon Ka Hai Jalwa!” Beautiful chaos follows, until Chakraborty’s fire soon disintegrates into embers with some final ramblings. “You bitch,” he says—the last words in the song, a final displacement of the male protagonist’s own culpability.

And after the rage, comes the sorrow.

The ballad “Nayan Tarse” opens with a feeling of informal dissonance, of tweaking, tuning instruments, of a sound check, of being unsure, of being afraid to get started, before the soundscape builds up to something frightening ahead. By the time Trivedi first croons the words, “Nayan Tarse”, we feel the impact of soul or emo-rock, but all backed up with a looping drum beat found in old-school hip hop as well.

Another soulful rock ballad—this one peppered with influences of ghazal and Hindustani music—is “Saali Khushi”. Trivedi begins singing acapella, before a soft piano helps to provide a soundtrack for the yearning: Where has that damn joy all gone away to? “Aaaya Oooh… Aaaya oooh”. Spiralling synths follow, another feature that repeats here after tracks like the rock “Emotional Attyachaar”, “Nayan Tarse”, “Pardesi”, and “Aankh Micholi”. It’s the sound of imperfection and discord.

And then… the drop. The drums—first heard in “Pardesi”—are now slower, mournful. They make the listener wait. “Saali Khushi” gets tipsy and then it gets woozy, rolling into a mind-mesmerizing drug high. A dance break ascends into a cacophony of different sounds we’ve heard elsewhere on the album: a trumpet solo, pianos, the melodious chanting of men, a rising before the barren fall. It’s dark and distrustful. “Saanp jaise kaali raatein hai, hain zahar si zindagi.” Nights black like snakes, a life all poisoned.

Dev isn’t the only one left broken-hearted. Paro has had to deal with heartbreak, too—although she comes out of it with her sanity intact, with a deliberate focus on making the best of her post-Dev life. The song “Ranjhana” by Shilpa Rao and Kshitij Tarey is a ballad from the female perspective, while “Mahi Mennu (Sad Version)” follows like a mellow postscript to the original, this time, embracing and drowning in the sorrow of the song’s true themes.

And then, there’s Leni (or Chanda), whose young life is the most tragic of all: her family and personal life are destroyed, her options lead her down the path of desperation. Despite this, however—or perhaps, as a result of being so battle-tested—the songs about Leni are the ones most filled with feelings of bliss and optimism. They are songs of sunshine, or, at the very least, of silver-linings.

The film itself is perhaps best summarized by the famous chorus of “Emosanal Attyachaar”: “Tauba Tera Jalwa, Tauba Tera Pyaar, Tera Emosanal Attyachaar.” Passion, love, and torture, all set to the dholak rhythm and a frenetic party beat. The scars with the smiles, the imperfections of every fairy-tale.

“Yahi Meri Zindagi” begins almost like a happy Disney song, as if a princess is being awakened to the sound of twittering birds as she gets dressed for the day. It’s a track about innocence, about basking in the first rays of the morning sun, instead of worrying about the darkness that the rest of the day will offer. The protagonist here is simply grateful to be alive—aided by Aditi Singh Sharma’s sultry, positive voice.

The light, ‘Disney’ themes are prevalent in “Dil Mein Jaagi”, featuring a peppy piano tune and Anusha Mani’s vocals that dance with innocent mischief. The song ends with a great upward musical flourish. “Lagta hai saara jahaan hai mera.”—The whole world could be mine—positivity spilling over the brim.

“Paayalia”—written and sung by Shruti Pathak—is the longest number on the album, featuring many familiar themes of longing and separation common to old Bollywood love songs. It’s ode to the songs most likely to be sung by a consort at a mehfil: Pathak’s vocals have to seduce the men in the audience, while also lay bare the performer’s own pain.

In Trivedi’s hands, however, nothing is a copy, and everything is an evolution. About 40 seconds in, “Paayalia” turns into a dance number, with drums urging you to keep pace, move forward to the future. There aren’t any glittering gold palaces where Devdas finds his consorts. These are the gullies of Paharganj, and she isn’t your grandfather’s Chandramukhi.

Tracks like “Ek Hulchul Si” and the two “Dev-Chanda” themes offer more pep to the ‘Leni’-themed sections of the soundtrack. “Ek Hulchul Si”—performed by Joi Barua—is almost the antithesis to the angry rock “Emotional Attyachaar”, now using the same instruments for sunshine and bliss rather than doom and gloom. Both the “Dev-Chanda” themes—showered with keyboards and whistles—give a feeling of rebirth, a tepid feeling of… Well things aren’t perfect… but they'll be okay!

If you haven’t seen the film, this is as much of a spoiler as I’ll offer.

In the album’s diversity of musical influences, Trivedi was able to provide the perfect accompaniment to the narrative’s emotional seesaws: its angsts, its joys, its celebrations, its heartbreaks, its nods to the past, its ambitions for the future. The soundtrack won him the R. D. Burman Award and the Best Background Score at the 2010 Filmfare Awards 2010 and later, the National Film Award for Best Music Direction—the highest such honour for Indian composers.

And, all these years later, the music of Dev.D still sounds fresh and truly imaginative, honouring Indian traditions while pushing the envelope of a global sound, paying homage to all versions of Devdas that came before, while bringing the emotions of this old story into a new millennium.

The film itself is perhaps best summarized by the famous chorus of the brass band version of “Emosanal Attyachaar”: “Tauba Tera Jalwa, Tauba Tera Pyaar, Tera Emosanal Attyachaar.” Passion, love, and torture, all set to the dholak rhythm and a frenetic party beat. The scars with the smiles, the imperfections of every fairy-tale. It delivered a clear glimpse the darkness concealed behind all the fun. It’s absolutely perfect.

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar. His debut novel A Beautiful Decay (Aleph Book Company) was published in October 2022. His creative work has appeared in Epiphany, Sycamore Review, Gargoyle, The Literary Review, The Bombay Review, and the anthology A Case of Indian Marvels. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, Fifty Two, FirstPost, and more. You can find him on Twitter: @karanmadhok1 and Instagram: @karanmadhok.