Masterpieces Under Our Feet

Photo: Karan Madhok

How a collaborative effort of designers and weavers have produced a distinct—and evolving—artistic vision on Indian-manufactured rugs

They may share a surname, but Ramesh Rajbhar and Tulsi Rajbhar are otherwise unrelated. They also share a vocation: both are bunkars—weavers—in the Varanasi area, master specialists in an art-form that has been passed down through generations in this part of the world. They sit in a room of bricks: red brick walls around them and red brick mounts on the floor to serve as their seats. They face in front of them an eight-feet tall loom, supporting a grey, unfinished rug that partitions this brick room into two halves.

Weaving away in a workshop in the outskirts of Varanasi, Ramesh and Tulsi will be here for weeks, even months, together. They will work with their hands to weave, cut and sew, with their feet to pedal, and they will brush and clean. They will be the skilled hands that will create yet another masterpiece.

Both men are in their mid to late 30s. Tulsi has been a weaver for about fifteen years, learning the skill from his brothers, who are trained in the same occupation. Ramesh is from a village near Bhabua in Bihar, farther east of Varanasi. He has been a bunkar for close to a decade. Like Tulsi, this is a family artisanal skill for Ramesh, too, passed on from his forefathers, his father, his brothers.

Varanasi is primarily popular for being the holiest of holy cities, the abode of Shiva and the Ganga and the ghats. But the city—and nearby Bhadohi—are also hotspots of one of the world’s most-thriving handloom-weaving industries. For over a century, the bunkars of this region have been practicing and perfecting the art of hand-weaving Persian rugs, which often make their way into the hands—or under the feet—of some of the top designers, hotels, and high-end customers around the planet.

But in recent years, this long-practiced art-form has been forced to welcome a crucial change. The traditional style, where a small ‘block’ of colours, shapes, or symbols gets repeated across the larger expanse of the Persian rug, is now giving way to a ‘modern’ design, where that symmetry can be lost, and the art weaved on the carpets is a lot more unpredictable, pushing the bunkars to unlearn generations-old mindsets and pick up new intuitions, skills, and artistic sensibilities.

All this, in the face of rising competition from machine-med alternatives, a hunt for other, more lucrative economic vocations, and the uncertain grey area that lies in the post-COVID-19 future.

Before this opaque future, most of the carpets that bunkars like Ramesh and Tulsi weave end up being passed on from local carpet sellers to middlemen and designers offering them to customers abroad, to customers in the US, Europe, Australia, and more who collect luxury items for their household or their place of business—specifically, hotels. Some of these carpets will be sold for hundreds of dollars, some for thousands, some even more. They will line hotel lobby floors, or serve as canvases to reproduce a work of art often as dense as any of the great masterworks.

“I can do both styles now,” Tulsi said of juggling between the traditional and the modern. “The modern one is obviously more difficult. In the ‘plain’ one, the design was easy to follow. They show us a photo or a ‘map’, and we just have had to copy it to do our work. But in the new style, the map keeps changing.”

The ‘map’ that Tulsi refers to is also known as the plate, or the template, a printed copy of the carpet’s colour-and-design scheme, created from computer applications by the designers behind the project. Ramesh Rajbhar said that copying from the map had been simpler in the past—“it shows us the colours, blue, green, whatever, and we just copy it”—but modern designs challenged this ‘simplicity’. Now, there wasn’t just one small template to reproduce over the larger expanse, but a different plate for each square to be woven.

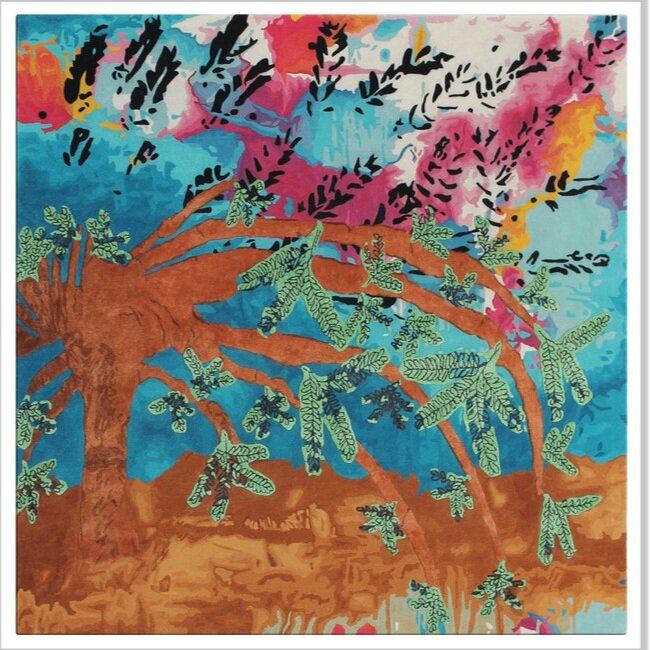

‘Panache’. A carpet woven in the classic style. Photo: Cocoon Fine Rugs.

“The traditional style also needs a map,” said Shantanu Paul, the vice-president and lead designer of a manufacturing and exporting company from Varanasi, SpaulRugs. “But in the traditional style, there has always been a fixed pattern. There is definitely a struggle for the weavers now going into the modern designs. They always have to keep their eyes on the map, always see where it changes. If they see they’re making a flower here, then the next flower might not be the same.”

“They [the weavers] like to make traditional designs… because traditional designs are repetitive,” said Paul. “Out of one quarter of a map, you can make the full carpet. If one person says one thing on this side, the other person can repeat the same one on the other. And it goes on like that.”

“In the modern design, everything changes from everywhere. It’s like a painting, which might require totally different weaving skills. Everything about these carpets is more expensive, including the weaving process itself.”

*

Most historians agree that the art of weaving Persian rugs was brought to India by the Mughals. Akbar, the third in the line of Mughal emperors, brought in carpet weavers from Persia to introduce the art-form in India, to hand-weave rugs for the imperial courts. Akbar established weaving centres in Agra, Delhi, and Lahore at first. These rugs were heavily inspired by Persian design aesthetics and motifs—designs that have since been adopted and ingrained with the weaving tradition in India, too.

The colours on the rugs came from natural dyes or vegetables dyes, extracted from plants, rocks, minerals, and insects. Rugs were woven with wool, velvets, silk, and even the expensive pashmina material.

In his 2014 research paper, Md. Ali Nasir wrote that the carpet industry soon flourished in the North of India, in Kashmir, Jaipur, Agra, Mirzapur, Jaipur, Bikaner, and Bhadohi. The centres in Uttar Pradesh, in particular, have since been famed for their colours and designs. Bhadohi, a town with the population of around one lakh 45 kilometres west of Varanasi, has become home to the largest hand-knotted carpet-weaving industry in all of South Asia.

There are two major types of handmade processes in the industry: hand-tufted and hand-woven. In the hand-tufted technique, carpets have their pile injected into a backing material with the help of a tufting gun, which is also bonded to a backing cloth. The tufted carpet, Nasir writes, can be produced either with a loop pile or cut pile. The broader category of hand-woven carpets—which include traditional knotted Persian carpets—are woven by hand over a loom.

Pranay Patodia is the director of Hands, a major carpet-production and export business that produces their textiles in Bhadohi, has showrooms in New Delhi, Mumbai, and Dubai, and exports luxury hand-woven carpets to all over the world. Patodia said that Hands traces its inception to the early days of the carpet-weaving boom in Bhadohi in the late 1880s, with interest growing from English merchants to export the local-made carpets to Europe.

The irony of the carpet-production business in India is of how few of the carpets are actually sold in India. “Our main market is the US, Europe, Australia, or the Middle East,” said Patodia. “India is a good market, too, but not as much as abroad. Colder countries in general have more of a demand for these carpets. Arab countries are an exception, for whom it is part of their organic culture and have long been a long part of their lifestyle.”

“There have to be inconsistencies,” said Paul. “Some kind of imperfection, some kind of human error. It’s got to have some depiction of the person who made it. There will be some colour, something gone wrong. It won’t be ‘perfect’, like a machine made it. Two handmade carpets will never come out the same, no matter what.”

“The affluent class might in India might want carpets, and if they do, they usually prefer machine-made.”

Paul confirmed this discrepancy of foreign and Indian customers. “Most customers in the industry are exported to be sold abroad,” he said. “Not just for me—but for 99 percent of the industry.”

“One simple reason is that the retail cost for the carpets we make are still high. For example, if we have a decent, small carpet—a five-by-eight—it might retail at around $2500. That’s close to two lakhs. This could be carpet of wool, wool-viscose, viscose-fibre, whatever. A carpet like this is difficult to sell to the Indian market… Machine-made carpets usually retail at just 1/10th of the price.”

“Now, things are opening up in the big cities,” Paul added. “So, there are more high-end customers. But most of the middle-class in India only buy carpets that are ‘low’ end or rejects—rejects are the ones where the colour didn’t come out right, or the order got cancelled for some reason.”

“If you look at the past, maybe a few decades ago, the carpet industry was probably 50% handmade and 50% by machine. Now, I would say only 10-20 percent of the industry is of handmade carpets.”

In recent years, the machine-made industry has become so sophisticated in mimicking expert designs that, Paul says they are doing the ‘unthinkable’. “They are getting better by the day,” he said. “But for those people who really understand carpets: interior designers, our customers who could be installing the rugs in millionaire-homes, they won’t go for a machine-made one. For them, the art exists in the hand-woven rug.”

Even now, it could take several weeks for craftsmen to make a medium-quality, household carpet. The most widely-used yarn according to many is wool, while other materials like artificial viscose and pure silk are also used. The yarn is then colour-dyed. “Designers require an expert, experienced eye to understand colour production,” said Patodia, “and how the dyes will appear on the yarn, what effect it will have under different lights, etc. A lot of the process hasn’t changed over the past century, but technology has indeed helped with the design process.”

*

Paul spends a lot of his day on the internet.

“Basically, my research is a lot of net-surfing,” he said. “I go through a lot of Instagram posts, or Pinterest. If you look at a thousand plates or pictures in a week, your mind automatically begins to have a filter of the current trends. Over a period of time, when you see so much, you learn how to adapt, what to add and subtract. You try to make something from this perception you have in your mind now of a carpet design.”

‘Banksy’, a more ‘modern’ design. Photo: Cocoon Fine Rungs

“That’s the way I work.”

Paul’s process has similarities to anyone with a visual or artistic brain, anyone that takes examples from the environment or the colour-schemes of the world, remixes it, and creates something else. He looks at paintings, modern art, textures, wallpapers, even concrete textures, and then takes from there. He has found inspiration in nature, with carpet designs that resemble tree barks or rock formations.”

While Paul doesn’t have any formal training in the ‘art’ behind the carpet design, he has help nearby. Bhadohi is also hope to the Indian Institute of Carpet Technology (IICT), a college under the aegis of the Ministry of Textiles that is among the few of its kind, teaching students the technical knowhow of carpet design from a liberal arts perspective. Students, who often have an art background, come home with knowledge of design history and of how to use new computer software or applications used for creating the ‘plates’.

For the more unconventional, modern designs, a request could be made by the customer or the interior-designer, or the manufacturer could produce a new thing to present to the customers and get artistic feedback. A designer like Paul will usually draw out his ‘vision’ by hand first, and then draw it on the computer. The design will have to be three-dimensional to reflect the texture and colour in the carpet’s depth.

It may be an art-form dating back hundreds of years, but carpet design in the 21st century requires a healthy leave of computer expertise, too. Paul, for instance, uses a software like Adobe to design, and then fine-tunes his designs with a specific carpet-designing programme, NedGraphics, for mapping. Then, he will likely use another programme called Galaincha for visualisation of what the end-product will look like. Once he has a plate or a template ready to ‘visualise’, he will then change the colour or design pattern according to what he or the end-customers requires: sometimes clearing it up; sometimes making it ‘busier’.

Paul also added that keeping up with global design trends helps him plan for future demands of his customers. “Colour sense changes from country to country,” he said. “You have a totally different set of colour schemes in America. Different in Europe—in Germany, Italy, they follow different colour patterns that are in vogue in these countries.”

In the traditional style of carpet design, every pattern and every colour had a deeper meaning, symbolism that communicated through art. In his paper for Abhijna Museum, Nasir described the symbolism in greater detail, with a list of what some of the designs symbolise:

Patterns like flowers, arabesques, rhomboids and occasional animal design were common produced and employed as designs. Each of these designs has a unique meaning. For example, the circle, zigzag and tree signified eternity, light and happiness respectively. Later, Persian style was amalgamated with Indian design giving rise to Indo-Islamic carpet.

Cypree Tree: Survival in the afterlife.

Anar (Pomegranate): Riches in abundance.

Peacock: The sacred bird.

Comb: Cleanliness; pillar of faith in Islam.

Weeping willow: Death, Sorrow, Grief.

Dogs: To protect the owner or user from theft.

Nasir also noted the symbolism of colours used for the carpets:

White: The colour of mourning, death and grief. Also symbolic of peace and purity.

Black: Revolt, Destruction.

Red: Joy, Happiness, Wealth.

Gold: Power, Wealth.

Dark Blue: The heavenly colour and also colour of morning.

“The design plays a part [for rugs] but more important is the number of colours used,” said Paul, “Some carpets can have fifty or sixty colours, and it can be tough; only the expert [weavers] can really work with so many colours and that kind of high quality.”

“Generally, we deal with natural colours, colours that aren’t bright, like greys, beige, charcoal. That is what I like, and what basically tends to sell for us. It can go with any room. It’s the easiest thing to fix and put anywhere.”

Some of the carpets that Paul’s company created were from art-work by Wendell Castle, who was considered as the father of the American studio furniture movement, and was also an artist. Castle passed away in 2018, but his work was passed on to the hands of weavers in Bhadohi, who turned the colourful paintings into breath-taking rug-art for a Milan-based company. The designer carpets by SPaulRugs inspire by Castle and Louis Lelo have been displayed at the 2018 Venice Biennial. “They are like art-pieces, collectible items,” said Paul. “We can’t afford to make more than a couple of them.”

Patodia, of Hands, took a unique approach in his company’s crossover into the art world. To mark 2020 as ‘The Year of Tolerance’ in the UAE, Hands worked with children of Dubai’s Senses Centre for Special Needs to create two canvases in various mediums, depicting the nation’s national tree, the Ghaf. The kids used mixed-media to paint and paste the two different designs Then, Hands wove made a carpet combining these two paintings. The ‘Carpet of Tolerance’ used thirty-one colours and combinations, was made with fine silk and New Zealand wool, and was ultimately hand-tufted in Bhadohi. The entire process took about four months to finish.

“I get my personal inspirations from various places,” said Patodia. “Market trends, colour trends, things that come out at various exhibitions. We can pick up patterns from textures from the internet. Everyone is online today; that is the biggest encyclopaedia.”

‘Rain Bird’. Photo via: Amini Carpets / Wendell Castle

“We've recently done a carpet which was a collage of various singers like Michael Jackson, Prince, George Michael, etc. Before that, we made a collage of the work of Salvodar Dali.” The Delhi store of Hands welcomes customers with a massive hanging carpet depicting Dali’s rose, from his famous 1958 painting Rose Meditative.

More recently, Hands have developed their ‘forma’ collection, a design that gives the illusion of multi-dimensionality, using a mixture of straight lines and curves, pulling the viewer into a hypnotic vortex. But they also continue more old-fashioned designs like the French Savonnerie, designs which give the traditional centrepiece or ‘darbar’ appearance.

Patodia added that, for their ‘regular’ orders, the idea for a design will often come from the customer or the interior designers hired by the customer. And in recent years, the designs have become more ambitious, involving greater skill at all levels of production.

“The designs have been inspired from the furniture-side,” said Patodia. “Carpets are often inspired by furniture, and then, the tapestry, the wallpaper. When contemporary furniture became to be made with more straight lines and fewer curves, our rugs, too, began to woven with more ‘lines’.”

“But some traditional carpets still look good. So, it's purely about the interior of the space.”

The challenge of more colours and more design deviations has increased with the demand to the modern style. Jaipur-based company Cocoon has been a leading name in designer and finer handmade rugs in India, with over forty years of experience of manufacturing and exporting carpets; their managing partner, Ayush Choudhary, also spoke about the initial challenges of this design switch.

“They [the weavers] have been weaving traditional style so many years,” said Choudhary. “This is an art-form that once came to India from the Mughals—and now, we have crazy colours and designs. Initially, it was challenging. Our weavers didn’t know head or tail of the switch. How do you make them buy into your vision? At the beginning, there were so many rugs that came off the loom that weren’t perfect, where the knots weren’t done right, there were rejected and returned.”

“But with time, the weavers took to it like a fish takes to water. We can also now pay them more, because our customers pay us more for the modern designs. [The weavers] were able to understand the value of the complex design and follow it to a ‘T’.”

“There has been a drastic change in the last fifteen years,” said Choudhary. “with the internet, Instagram, Pinterest, changing design trends. Persian style rugs that have been around for hundreds of years are now becoming fashion objects with fall, spring, and summer collections.”

“This has also got to do with homes starting to change. Now, homes are being redesigned every four or five years. So, interior designers are trying to tell different stories, in a different language. This has led to frequent change of rugs, furniture, lighting, etc.”

The Carpet of Tolerance. Image courtesy: Hands Carpets

Choudhary said that Cocoon’s signature design is in the use of ‘friendly’ colours that are not jarring to the eye. His designers, he says, have had to evolve over the years, too, from pen and paper to computers, and in thinking creatively outside the box to vision the traditional designs in more modern ways.

Choudhary sites a variety of artists and designers who have influenced his own vision, ever since he began working in the field over a decade ago. “One of the artists I really admire is Jackson Pollack,” he said. “He set us down the path of modern, contemporary-style rugs. We've done work with lots of other artists that inspired us. Right now, we are making designs that are ‘Bauhaus’-themed.”

Cocoon’s design and experimentation has brought it accolades within the larger industry, specifically with awards and acknowledgement at DOMOTEX, a major carpet trade show in Hanover, Germany. Choudhary added that the company has done collaborations with various designers in other fields of art, from fashion designers, interior designers, to architects. In India, their recent collaboration was with designer and architect Ashish Shah, designs that were inspired by Le Corbuier’s architecture in Chandigarh.

“We function like a boutique company,” said Choudhary.

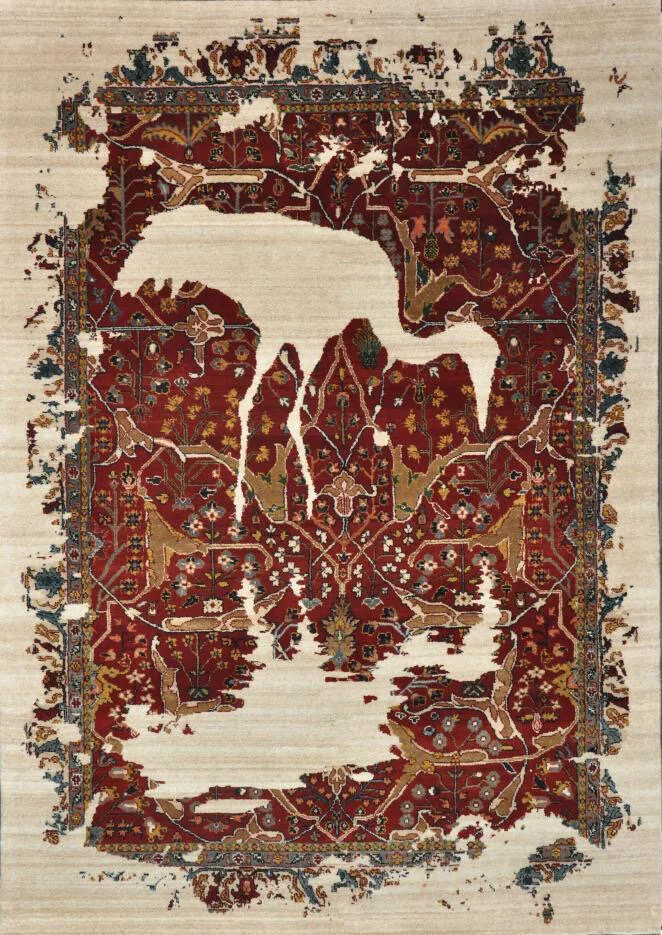

Those in the carpet business also have an acute eye of spotting the level of expertise that goes into each carpet, from the simplest designs to the art reproduction of masterpieces. Paul said that, even with the increase in machine-made rugs, it is fairly easy for him to tell which ones are hand-woven, by seeing the knotting in the back. Among other factors he mentioned, one of the curious tell-tale signs in a higher-quality carpet—a hand-woven one—is in its flaws.

“There have to be inconsistencies,” said Paul. “Some kind of imperfection, some kind of human error. It’s got to have some depiction of the person who made it. There will be some colour, something gone wrong. It won’t be ‘perfect’, like a machine made it. Two handmade carpets will never come out the same, no matter what.”

“Human error has an organic feel to it.”

*

Head out to any of the handloom workshops now, and what you’re likely to find is an eerily, deadly silence. There is no familiar ‘buzz’ of the loom, no feet tapping on pedals, no wet squish of a rug being colour dyed or washed.

As fear of the COVID-19 pandemic first began to spread worldwide, international orders for many of the manufacturers in India began to slow down, before being completely suspended. Then, the liners and shipments going out of India for export became more expensive, adding greater stress to the investments of both the customers and the producers. And finally, near the end of March, came the full, nation-wide lockdown, forcing all the industries, from Jaipur to Bhadohi, to close down its shutters for the foreseeable future.

In a connected world, and especially a business so reliant on imports and exports, it is common for international incidents to affect the Indian textile industry. In 2008, for example, Varanasi’s famed silk industry was completely disrupted by the Sichuan Earthquake: the loss of life and business in China pushed down imports and pushed up prices.

With the worldwide pandemic caused by the coronavirus, however, that finish line stands far and hazy. Even as China—one of the major providers of raw material—hurryingly opens up its businesses, the rest of the world continues to stay shut and keep its distance. In India, the lack of work has led many of the poorest, including the labourers and artisans of the carpet industry, to the brink of desperation and starvation.

But there always seemed to be a finish line in the recent disruptions, a promise that things would soon get better, ‘normalise’, that business would go on as usual. With the worldwide pandemic caused by the coronavirus, however, that finish line stands far and hazy. Even as China—one of the major providers of raw material—hurryingly opens up its businesses, the rest of the world continues to stay shut and keep its distance. In India, the lack of work has led many of the poorest, including the labourers and artisans of the carpet industry, to the brink of desperation and starvation.

Recently, the chief mentor of The Clothing Manufacturers Association of India (CMAI) Rahul Mehta told Outlook Magazine that he estimated a loss of 10 million jobs in the textile sector if there is no government-driven stimulus package. This loss will be particularly harsh in this industry considering that much of the production side is part of the informal economy.

The India Carpet Expo, the largest handmade carpet fair in Asia, was scheduled to be held in New Delhi from March 28-31, and was hence postponed due to COVID-19 and the national lockdown. This was to be the 40th edition of the expo, which is held twice a year, in New Delhi and in Varanasi. In a report by The Times of India, the executive director of the Carpet Export Promotion Council (CEPC) Sanjay Kumar said that an estimated business of around Rs. 400 crores would be affected due to the postponement of the event.

Patodia said that, before the lockdown, Hands were still completing their earlier orders, but all future orders have now been put on hold. “We took all the precautions we could at first, but things have changed. Now, we can expect a slowdown,” he said. “Hotels that order from us around the world are stopping their purchases; they have lower occupancy, and perhaps not the funds they have allocated for purchasing carpets. The impact is sneaking in.”

“Work was normal until recently,” Paul said, before the national lockdown. “But in the last few days, I tried to do as much as possible, because we knew we would have to close down soon. All our customers from the US and more stopped taking any orders. Nothing is getting exported. I think that, at least for the next two months, nothing will happen [in the industry].”

“We don’t yet know about what will happen in the long-term,” added Paul. “Ours is a luxury good, so we hope to recover quickly.”

However, even if the carpet industry recovers from after-effects of the current pandemic, it will continue to play a major role in larger environmental issues. One of the major basic ‘ingredients’ in any textile industry is viscose, the third most-commonly used textile fibre in the world. In a recent piece for Good On You, Lara Robertson explained that viscose (otherwise known as rayon) is a semi-synthetic fibre made from trees, and is popular as a cheaper and more durable alternative to silk. Viscose shows up in our clothes, upholstery, cellophane, bedding, and of course, in carpets.

In her piece, ‘Material Guide: Is Viscose Really Better For the Environment’, Robertson writes:

As a plant-based fibre, viscose is not inherently toxic or polluting. However, because of the growing fast fashion industry, much of the viscose on the market today is manufactured cheaply using energy, water, and chemically-intensive processes that have devastating impacts on workers, local communities, and the environment. This is why viscose (including bamboo viscose) was given ‘D’ and ‘E’ scores for sustainability in the Made-By Environmental Benchmark for Fibres.

Robertson adds that the production of viscose is contributing to the rapid depletion of the world’s forests, which are being cleared to make way for pulpwood plantations.

More specifically closer to home, the textile dyeing and finishing industry has been a major pollutant to our rivers and environment, as one of the most chemically-intensive industries on Earth, and one of the top polluters of clean water. In her 2012 paper ‘Textile dye industry an environmental hazard’, Rita Kant mentioned that natural dyestuffs can require large quantities of water—almost equal to or double the fibre’s own weight. “About 80 percent of the dyestuffs stay on the fabric, while the rest go down the drain,” Kant wrote.

The Bidjar Reflection. Image: SPaulRugs

“Large quantities of water are required for textile processing, dyeing and printing. The daily water consumption of an average sized textile mill having a production of about 8000 kg of fabric per day is about 1.6 million liters.”

In Varanasi, close to Bhadohi which is the capital of the carpet industry, the Ganga river has long fallen victim to the pollutants caused by dyeing and printing units for saris, rugs, etc. It is an ongoing tug-and-pull in the region, one that needs the tourism, spiritual connect, and environmental benefits provided by the ‘holy river’, but has also benefitted in its economy and the livelihood of its residents/migrants that is provided by the globally-successful textile industries.

*

Little of this story can be told without the artists—or artisans—behind the art. After decades of their more predictable formula—passing on the art-form of handloom from father to son, one generation to another—there is now turbulence in the lives of many weavers. The current generation of weavers have been the first to be pushed aggressively to adapt to a new style, to weave in a more unpredictable fashion, to recognise the whole forest instead of just the trees.

And now, with turmoil of the industry following the pandemic, they face a challenge to their profession unlike ever more.

Even before the coronavirus, Paul told me that the number of young artisans learning the craft was much lower than the past. “Often, we see there a number of older weavers working on the handlooms, so old that they’re losing their eyesight and can’t weave very fine material, so they have to work with lower quality.”

“There are weavers who have only done the traditional-style all their lives,” said Patodia. “They find it difficult to do the new type of hand-tufting. You have to make sure to choose the right weavers, the ones who will be able to adapt to new requirements.”

The ones who have been able to adapt, and those who may be able to return to work once the fear of the virus is over, will likely grow greater in demand. It is a rare talent to work on those large looms for weeks and months, operating with delicate fingers even in testing conditions, sometimes only seeing a small ‘plate’ of the larger art-work.

It is a collaborative effort, creating a masterpiece on a rug: involving interior decorators; customers with specific aesthetic tastes; designers who envision new colours and shapes on paper, on their computer screens, on the ‘plates’; and eventually, the weavers themselves, who give this design life by translating the plates on to the rugs themselves. Their paintbrushes are their fingers and feet; their colours are the wool, silk, or viscose they use to weave; and their canvas is the rug itself.

Even after the onslaught of competition from machine-made rugs or a ‘force majeure’ event like the COVID-19, the industry will likely continue to survive as an acquired taste, like art itself, because whether the masterpieces end up under our feet or hanging on walls, they have the staying power to remain relevant beyond their years.

“Eventually, a rug ties up the entire space properly,” said Choudhary. “A space with a rug just looks more complete… It’s like art on the floor.”

***

Karan Madhok is a writer, journalist, and editor of The Chakkar, whose fiction, translation, and poetry have appeared in Gargoyle, The Literary Review, F(r)iction, and more. He is the founder of the Indian basketball blog Hoopistani and has contributed to NBA India, SLAM Magazine, FirstPost, and more. Karan is currently working on his first novel. Twitter: @karanmadhok1